Khaled Mahmoud

Contrary to the usual, Egypt no longer ignores or underestimates human rights issues, but it also deals with them according to its vision, defying external pressures.

Perhaps the most accurate expression here is that Cairo no longer feels bound or subject to political blackmailing from its allies on the other side of the world regarding this controversial file.

The typical joke was that whenever Washington needed to pressure Cairo to pass a specific regional plan, it would call Egypt’s hotline for human rights and Copts. However, now things have changed.

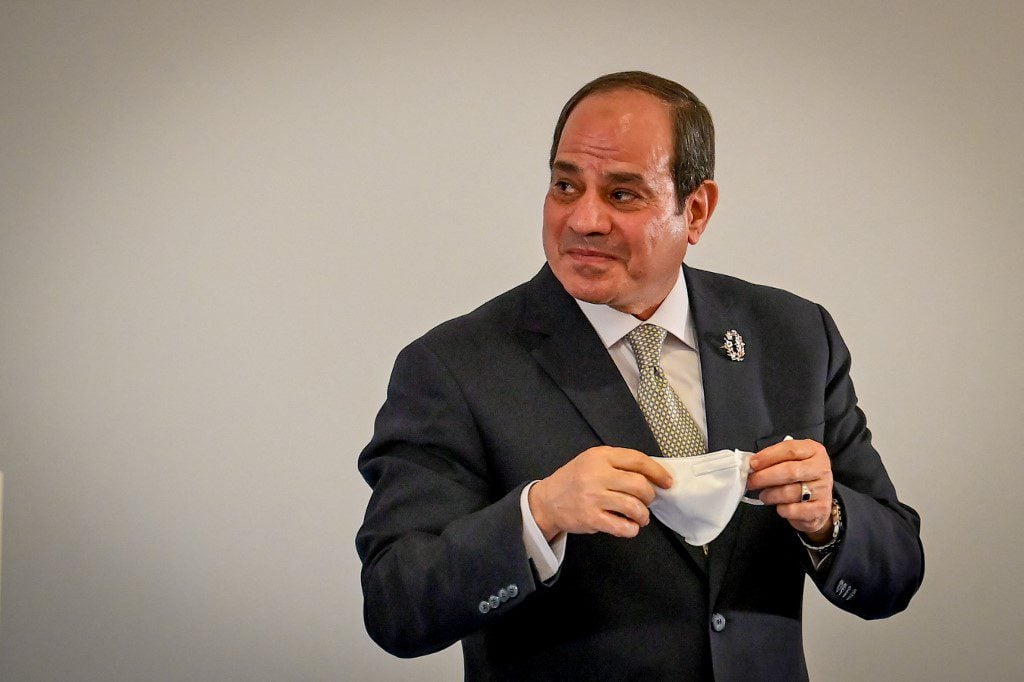

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi believes in the significance of citizens obtaining their rights to education, well-being, health and housing, and the luxury of expressing an opinion or engaging in activities that the state and its apparatus may not necessarily approve of.

An Ambitious Initiative

Months ago, Sisi presented an ambitious initiative, titled the National Strategy for Human Rights, to develop the performance of official and governmental bodies with this file and stave off suspicions about his regime by idleness in preventing abuses or committing human rights violations.

Since assuming power in 2014, Sisi has embarked on unprecedented internal reforms, affecting various aspects of living, including the inauguration of a new road map for movement between the different regions in the country and massive development projects, aiming to end the traditional living crises that Egyptians suffered in the past.

In his quest to build the new republic, al-Sisi collided with the human rights file, which Egypt had previously been keen to divert its dangerous and worrying effects on its relationship with local public opinion and also with its allies abroad, especially the United States.

Cairo still views itself as a significant partner for American interests in the Middle East. For example, Washington and the Biden administration have appreciated Sisi’s role in mitigating the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

From the official Egyptian point of view, Cairo’s role for Washington is indispensable in many regional files. Perhaps this prompts the official Egyptian decision-maker to separate human rights issues from the mutual relations with the States.

American Criticism

The administration of US President Joe Biden did not miss the chance to criticise Egypt’s human rights record.

Those classic criticisms from Washington no longer frighten Cairo, which has realised that the repeated American criticism, in particular, does not necessarily lead to harming of Egyptian-American relations.

Just hours after an Egyptian court handed down a five-year prison sentence on three, most notably activist Alaa Abdel-Fattah, last Monday, US State Department spokesman Ned Price expressed his country’s disappointment.

Considering that journalists and human rights defenders should exercise their freedom of expression without facing criminal penalties, Price said that US officials discussed human rights issues with their Egyptian counterparts and informed Cairo that relations between the United States and Egypt could be improved if progress was made on this issue.

However, Cairo’s response was fast. Ahmed Hafez, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said: “It is not appropriate at all to comment in any way on or refer to rulings issued by the judiciary in compliance with laws and based on irrefutable and conclusive evidence in a fair, impartial and independent judicial process.”

Hafez added: “It is not permissible to address such judicial issues in any political framework, or link them to the course of relations between the two countries.”

This unusual tone of Egyptian diplomacy reflects, according to observers, in addition to the sensitivity of Cairo towards any criticism regarding human rights, Egyptian efforts to keep this file away from any political disputes in or outside.

In its annual report on the human rights situation in Egypt, the US State Department referred to “extrajudicial executions,” “enforced disappearances,” and violations of the “right to assembly and association”.

The recent criticism from the US State Department on the verdict of an Egyptian court that sentenced three activists, including a blogger and a lawyer, to four years in prison on charges of spreading false news, enraged and resented Cairo.

Alaa Abdel-Fattah, whose family complains about the severe conditions of his detention, was arrested after his release in 2019, knowing that he gained fame during the events of the 2011 revolution that toppled former President Hosni Mubarak after three decades in power.

In September 2021, the Biden administration threatened to withhold $130 million in US military aid to Egypt, hoping that the latter would take specific steps related to human rights.

Italy and France Join the Fray

This month, the Egyptian authorities temporarily released human rights researcher Patrick Zaki, who was arrested last year upon his return from Italy to Egypt and faced an up to five years’ prison sentence for “spreading false information” over an article in which he denounced discrimination against the Coptic minority in Egypt.

Zaki, who was officially granted Italian citizenship last April, after 22 months in pretrial detention, is awaiting the resumption of his trial in February 2022 on charges of spreading false information before the Mansoura Emergency State Security Misdemeanours Court.

Through his family, Zaki succeeded in mobilising an official Italian public opinion in his favour by collecting thousands of signatures on a petition for his release. Mario Draghi, the Italian Prime Minister, and Luigi Di Maio, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, follow up the case.

Italy’s relationship with Egypt is still suffering after the murder of the Italian researcher Giulio Regeni, whose body was found in 2016 lying naked and bearing signs of severe torture in a suburb of Cairo, where he was researching for a doctorate at Cambridge University.

While human rights organisations estimate the number of political detainees in Egypt at about 60,000, the Egyptian government denies the accusations related to prison conditions. It categorically denies the presence of “political prisoners”, and in turn, asserts that it is waging war against terrorism and confronting attempts to destabilise the country.

French President Emmanuel Macron is still timidly raising the issue of Egyptian-Palestinian political activist Ramy Shaath, who has been arrested for more than two years.

Among the new criticisms of Egypt’s human rights record under Sisi, several academics have been imprisoned in the past few years. Prominent activist and former parliament member Ziad al-Alimi was sentenced to five years and two others to four years in prison for spreading false news. The authorities also accused them of working with a group funded by the Muslim Brotherhood to incite revolution and commit violence.

While human rights groups say that the authorities have arrested tens of thousands, Sisi denies the existence of political prisoners or detainees and says that security and stability are paramount. His supporters believe that these measures are necessary to achieve stability.

A Special National Initiative

In the opening of the National Strategy for Human Rights, Sisi stressed that it “emerges from a subjective Egyptian philosophy that believes in the significance of achieving integration in the process of elevating society, which cannot be completed without a clear national strategy for human rights that deals with challenges as it takes the principles and values of Egyptian society into account.”

The time frame for implementing the strategy extends to five years. It includes four main axes: civil and political rights, economic rights, social and cultural rights, the rights of women and children, people with disabilities, youth and the elderly, education and capacity-building in human rights.

In its analysis of the strategy launched by Sisi on Sept. 11, 2021, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies concluded that “the strategy is rooted in the denial of the depths of Egypt’s human rights crisis” and it is “aiming to deceptively convey to the international community and donor states that political reform in Egypt is proceeding apace, thereby entrenching the tragic state of affairs and deflecting international criticism.”

According to this analysis, the 78-page strategy affirms that “the source of the human rights predicament in Egypt is the Egyptian people themselves, their limited understanding of human rights, and the dereliction of political parties and civil society. As such, the document does not pledge to put an end to daily acts of repression that violate Egypt’s constitution, law, and regulations, together with violating Egypt’s international obligations. Instead, it repeatedly recommends ‘raising awareness’ of citizens.”

The centre concludes that this strategy in itself is the latest official evidence of the absence of a political will, which explains what it called the unprecedented horrific deterioration of human rights in Egypt.

On the other hand, the Ra Center for Strategic Studies believes that the strategy confirms President Sisi’s belief in freedoms and democracy and works to strengthen it in various ways while ensuring the security and safety of society and protecting it from malicious and extremist ideas.

The centre called for launching several media campaigns on human rights values and codes during the next phase, in parallel with intensifying the efforts of religious and governmental institutions to emphasise values of citizenship, tolerance, dialogue and combating incitement to violence and discrimination.

It prompted the expansion of utilising modern technologies to develop citizens’ awareness of human rights.

In any case, the human rights issue still poses a headache for everyone, between Sisi’s reforms and his ambition for a new republic, and calls for him to direct his efforts to the internal political situation in isolation from the economic and social conditions.

Recently, Sisi has become aware of the significance of moving in this direction. Still, he never wants to allow the opportunity to repeat the fatal mistakes that prompted Egyptians to revolt against the rule of his late predecessor, Hosni Mubarak.

Between possibilities and hopes, Sisi remains haunted by concerns that improving the political climate will be at the expense of the state or the interests of the people who suffered greatly from their political and partisan elite that talk about human rights and ignore the need to improve infrastructure and develop various state institutions to be able to face economic challenges that surround a country the size of Egypt.