Libya is expected to hold presidential and legislative elections by the end of 2018, despite warnings that the country is too unstable to send voters to the ballot box. The biggest obstacle is that the country is still under the rule of militias, meaning that there are no guarantees that rival factions will respect the election outcome.

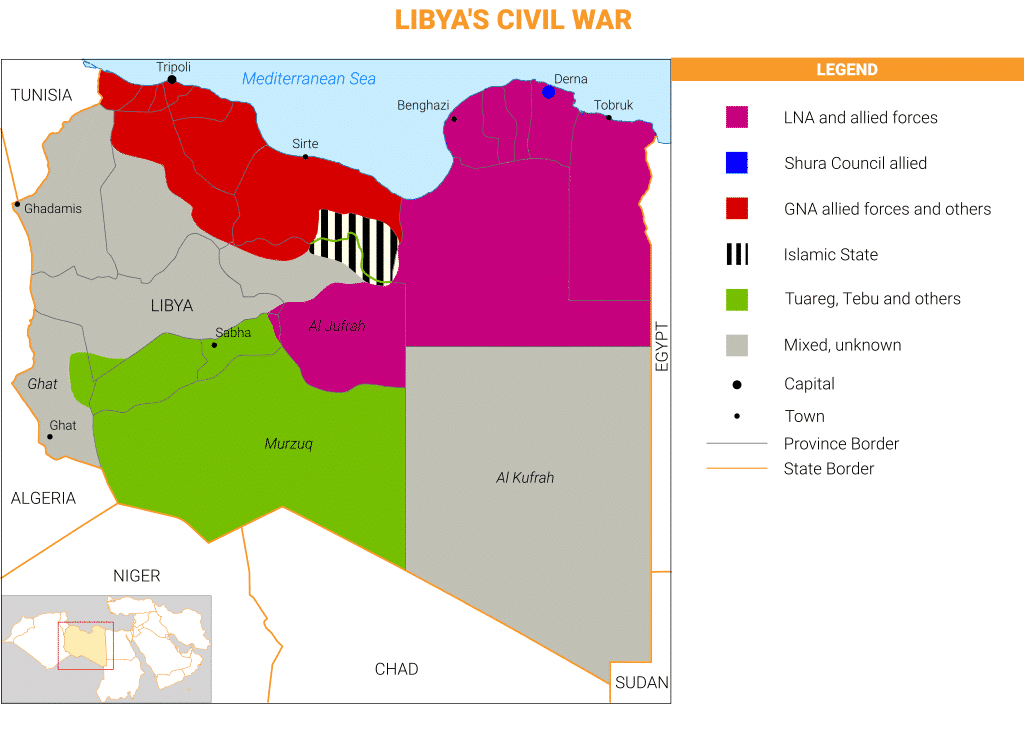

In the west of the country, the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) only has nominal control over cities and towns; in the east, General Khalifa Haftar and his self-described Libyan National Army (LNA) rule with an iron fist. Yet while Haftar supports elections, he explicitly threatened to retake the country by force if he does not like the result.

Many countries are nonetheless in favour of elections to secure their short-term interests. A Western diplomat told the BBC that France is one of the nations that is pushing hardest to send Libyans to the polls. “There is an awareness of how dangerous it can be to hold elections soon,” he said. “But we have to keep working towards a solution.”

Ghassan Salame, the UN envoy to Libya, also supports elections but stresses that an array of conditions first need to be met. His roadmap includes reducing the nine-member Presidential Council (PC), which heads the GNA, to just three. He then wants to hold a national conference before preparing for a referendum on a new proposed constitution. Completing each step, he stressed, is essential before holding an election.

Tarek Megerisi, a Libyan analyst and visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, wrote in a piece for Carnegie Endowment that political elites are obstructing Salame’s roadmap for personal gain. The House of Representatives (HoR), which is supposed to serve as the legislative body to the GNA, has not even passed an electoral law to pave the way for a constitutional referendum. That is largely because Agila Saleh, the HoR’s president, fears that any election under a constitutional Libya would limit his power.

Most Libyans, however, emphasize that adopting a new constitution is a must before holding elections. That way, Libya can at least have a legal blueprint to rebuild weak institutions. Laila Moghrabi, a Libyan journalist and writer, also stresses that militias need to disarm to ensure the country does not plunge deeper into turmoil following a nationwide vote.

“Militias are always against stability,” she told Fanack Chronicle. “For Libya to witness a peaceful transfer of authority, we need to disarm militias and establish an army. Only then can authorities enforce an election result.“

Human Rights Watch (HRW) agrees. In a statement released on 21 March 2018, the rights group urged Libya not to rush into elections.

“Libya today could not be further away from respect for the rule of law and human rights, let alone from acceptable conditions for free elections,” said Eric Goldstein, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at HRW. “The authorities need to be able to guarantee freedom of assembly, association and speech to anyone participating in the elections.”

Goldstein was vindicated after suicide bombers detonated themselves in the main office of Libya’s electoral commission in Tripoli on 1 May, killing 12 people. Islamic State (IS), which still has a presence in southern Libya, claimed responsibility.

The attack happened just two days after the Libya Quartet – a group comprising the League of Arab States, Africa Union, European Union and the United Nations – gathered in Cairo, Egypt to announce that the climate in Libya was suitable for an election.

However, anyone who has been paying attention to the civil war in Libya will question this assessment. In areas controlled by the Libyan National Army, people are not even free to declare their candidacy without reprisal. On 4 January, unknown gunmen killed Salah al-Qatrani, an education official, outside his home in a Benghazi suburb. The assassination took place just days after al-Qatrani announced his plan to run in parliamentary elections.

Freedom is far from guaranteed elsewhere in the country. That was clear after Muhammad Eshtewi, the mayor of the western port city of Misrata, was assassinated on 18 December 2017. Misrata, whose armed groups are nominally aligned with the GNA, is considered one of the more secure cities in the country.

Salem Hashem Ismail, an MP in the HoR, told reporters that various militias are attempting to sabotage the roadmap to elections by assassinating prominent figures, just as they did in 2014. Back then, Libya witnessed a spree of political assassinations leading up to a disastrous election on 25 June. The most high-profile killing occurred on election day when militants stormed into the home of Salwa Bughaighis, a prominent human rights lawyer, and shot her dead for presumably encouraging Libyans to vote.

Zahra Langhi, who co-founded the Libyan Women’s Platform for Peace with Bughaighis, told Zenith Magazine that she spoke with Bughaighis over the phone just moments before her death. She said she called Bughaighis immediately after she saw her post a photo on Facebook that showed her casting a vote in Benghazi.

“[Bughaighis] was aware of the risks. She told me, ‘Don’t worry Zahra, I’ll pack up and travel tomorrow,” recalled Langhi. “But I felt it. I told her, [Salwa] take care, the [militias] may do something mad.”

As various stakeholders push for elections again, Langhi told the news website al-Monitor that Libya could experience a worse cycle of violence than in 2014. She also stressed that Libya needs to engage in a state-building process before sending citizens to the ballot box. In her eyes, stability will not be achieved unless local conflicts are resolved and fragmented institutions are unified. Only once that happens, she said, can the country think about adopting a constitution and preparing for free and fair elections.

“If Libya has elections at the end of 2018, then [Libya] would be repeating a terrible mistake,” she told al-Monitor. “I’m certain that the election wouldn’t result in a peaceful transition of power.”