Egypt is preoccupied with the existential threat posed by the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which Egypt regards as more urgent and pressing than all the other threats facing national security. This is partly due to the fact that Egypt is largely powerless to stop the building of the dam on the Blue Nile except through diplomatic means, which are time-consuming and often end with compromise solutions that might see Egypt even worse off.

The 17th round of talks between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia, which share the river’s waters, ended on 13 November 2017 without an agreement being reached. Filling and operating the dam without affecting the downstream countries remain topics of dispute. On 18 November 2017, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said that “Egypt’s share of the Nile water is not negotiable”, adding that the issue is “a matter of life or death for the [Egyptian] people”.

However, Egypt has repeatedly denied any intention to disrupt the building of the dam militarily. For the time being, it is determined to seek politically negotiated solutions to the dispute, including submitting an objection before the United Nations Security Council in order to exert maximum diplomatic and political pressure on Ethiopia.

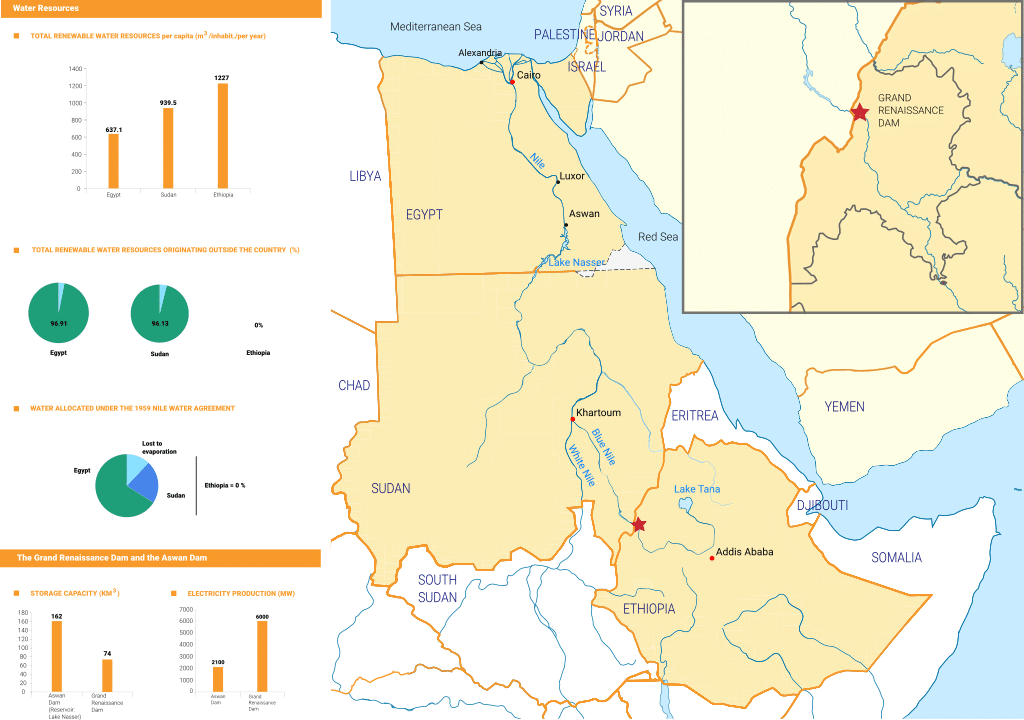

Ethiopia started construction of the dam in 2011 – the realization of a decades-long dream to change the fortunes of the impoverished country. The dam is being built in the Benishangul area of the Blue Nile, 40km from the Sudanese border and 700km from the capital Addis Ababa. The Blue Nile provides 86 per cent of the total Nile water revenues upon which Sudan relies partially and Egypt completely. The project is being implemented by the Italian company Salini Impregilo.

Once complete, the dam will have an estimated storage capacity of 74 billion cubic metres (BCM), which is almost equivalent to the water share of the Nile River of Egypt and Sudan combined, and generate more than 6,000 megawatts of electricity, approximately three times the production of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt.

The project will cost about $5 billion, which the Ethiopian government is struggling to make available from its own resources, the initial public offering and a limited sum of foreign loans.

Growing Egyptian Concern

Ethiopia has repeatedly stated that the dam is being constructed for electricity-generating purposes only, and that no water will be held or used for irrigation. Ethiopia has also said that the mountainous area in which the reservoir is being built is unsuitable for agriculture, and that it is committed to the principle of equitable and reasonable use of water resources.

These pronouncements have done little to reassure Egypt, which is concerned that filling the reservoir will threaten its share of the Nile waters unless a clear agreement is reached on how and when the dam will be filled.

Studies show that Egypt’s share of the Nile, which currently amounts to 55 BCM per year, as stipulated in the 1929 water agreement with the British, then a colonizing power, and the 1959 agreement with Sudan, is only half the amount it actually needs. This is despite the latter agreement allocating 2.5 times more water annually to Egypt than to Sudan, which receives 18 BCM.

Hostile response

Although Egypt’s concerns appear justified, Cairo’s response to the dam has long been hostile and shown little understanding of the legitimate interests of the other Nile Basin countries.

Egyptian anger came to head during a televised meeting on 3 June 2013, when Mohamed Morsi, then president, threatened to launch a military attack on Ethiopia. The threat was later retracted and the Egyptian government was quick to state that it did not represent the official position.

By contrast, President al-Sisi, who removed Morsi from power a month later in a military coup, has been more conciliatory. On 23 March 2015, he signed a declaration of principles to resolve the dispute with Sudanese President Omar Bashir and Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, under which the three countries pledged to reach a full agreement on filling and operating the dam. The agreement included ten basic principles that are consistent with the 1966 Helsinki Rules on the Uses of the Waters of International Rivers. At the signing, al-Sisi said, “The Renaissance Dam project is a source of development for millions of Ethiopian citizens through the production of clean and sustainable energy, but it is a cause of concern for their brothers living on the banks of the Nile in Egypt, who are almost equal in number.”

Egypt’s greatest fear is that Ethiopia will fill the reservoir in five years or less, which according to Egyptian estimates would deprive Egypt of its water resources, dry out a portion of its agricultural land and reduce the reservoir and power-generating capacity of its Aswan High Dam further downstream.

Some Egyptian reports also warned that the collapse of the dam would pose a threat to Sudan be-cause the dam is only 40km from the Sudanese border and less than 100km from Sudan’s Roseires Dam.

These warnings have gone unheeded by Khartoum, which did not hesitate to express its approval of the construction of the dam in 2011. At the time, the Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced, ‘The technical authorities in the Ministry of Electricity and Water Resources confirmed that the recent Ethiopian step does not harm Sudan and that the two countries have reached understandings on the issue.’

Dr Salman Muhammad Salman, an expert on international water disputes at the World Bank, said that the dam will certainly advance Sudanese interests because it will guarantee stable Blue Nile water revenues throughout the year and provide protection against dangerous annual floods.

It will also protect the strategic Roseires and Sanar dams against millions of tonnes of silt carried by the Blue Nile every year that reduce the storage capacity of the two dams by approximately half.

Moreover, the project will provide clean electric power at preferential prices for Sudan. Salman added, “Warning of the collapse of the dam is meaningless intimidation because Egypt has been running the Aswan High Dam for more than half a century, and Sudan is running five dams on three rivers, the oldest of which is 90 years old. So, why would the Ethiopian dam collapse when it is being built with better and more advanced know-how, expertise, technology and materials?”

However, other Sudanese experts question the benefits of the Renaissance Dam for Sudan, citing negative effects that are similar to those put forward by Egypt, namely that operating the project will reduce Sudan’s water resources and threaten agriculture.

Egypt has so far refused to show any understanding of Sudan’s support for the dam and continues to consider the Sudanese position as a stab in the back. The Egyptian press has also addressed the issue in angry and critical tones. According to Hani Raslan, deputy head of the al-Ahram Center for Strategic Studies in Cairo, this was a political position used by Khartoum for comprising with Egypt on other issues, which would exacerbate the tensions between the two countries. It should be noted that the ruling elites and opposition in Sudan agree that the 1959 Nile Water Agreement was unfair to their country, and some deem the Renaissance Dam to be compensation for the adverse effects of the agreement.

The dam is currently around 60 per cent complete, even though a technical study on the impact of the dam for Sudan and Egypt has yet to be completed. According to Atiya Issawi, who covers African affairs for Egypt’s al-Ahram newspaper, “Ethiopia wants to present Egypt with a fait accompli by [rushing] to complete the dam. It is thus ignoring Egypt’s comments on the construction in the hope that it will only have to negotiate the details of filling the dam’s reservoir and its operation, in a way that takes into account dams in Egypt and Sudan, so that they are coordinated [and do not block flow at the same time].”

He added that whatever solution is reached on the technical study, it will in some form be at the ex-pense of Egypt. “Egypt will not come out unscathed,” he said.