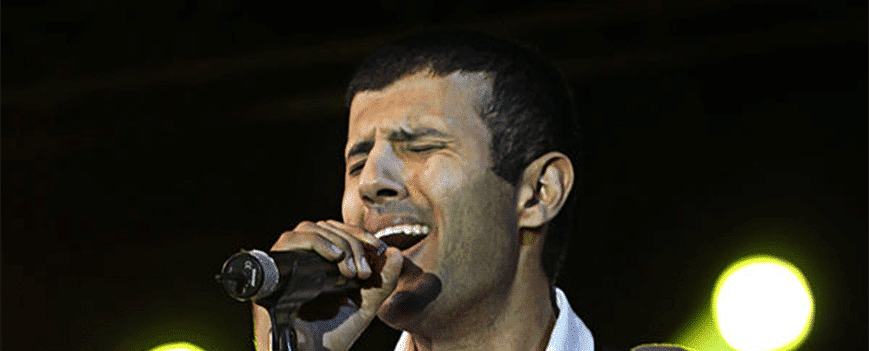

When young Egyptians took to the streets on 25 January 2011 to protest against the government, and eventually toppled long-time autocrat Hosni Mubarak, technology brought them together. However, music was one of the strongest rallying calls. And it was in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the epicentre of the revolution, where Hamza Namira rose to stardom.

Having grown up in Saudi Arabia, Namira returned to Egypt in 1992, aged 12, and became interested in music. He learned to play the guitar, keyboards and oud as a teenager. He joined a band headed by a Nabil Bakly, a relatively unknown artist whom Namira credits as his main musical influence. Soon after, he formed his own band and began singing in small gigs around the country.

His music, which mixed Egyptian folk with jazz, pop, rock and occasionally electro, began to attract attention. His lyrics focused on everyday issues with which young people struggled, such as poverty and political frustration. However, he also tried to offer a positive and hopeful message that resonated with his listeners, who started flocking to his live performances.

When the revolution erupted, however, everything changed. The album’s lead song, ‘Ehlam Maaya’ (‘dream with me ’), became a rallying call for young people hoping for a better future. Namira became a familiar face in Tahrir Square, joining the revolutionaries and publicly calling for Mubarak’s resignation. He would regularly perform in the square, and his songs were seen as embodying many of the values of the uprising. He soon became one of the artists of the revolution, his voice instantly recognizable to the hundreds of thousands of people who had taken to the street.

A few months after Mubarak stepped down, Namira released his second album, Insan (‘human’), which became an instant hit. The album was heavily inspired by the revolution, with the lead song drawing on the idealized values of humanity that were celebrated in Tahrir Square. Also on the album was a song called ‘El Midan’ (‘the square’), which celebrated the courage and strength of the revolutionaries. The songs became a staple on mainstream radio. His concerts grew in size, with thousands singing in unison as he praised the revolution or talked about a hopeful future for the country.

He was hailed as the new Sayed Darwish (1892-1923), an Egyptian singer and composer known for his large following and support for the common people. He also joined social media, attracting millions of followers on Facebook and Twitter.

However, his voice and art became too closely tied to the revolution. As the political winds changed, so did his fortunes. In July 2013, the popularly backed military coup led by Abdel Fattah al-Sisi ousted Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president. This was followed by a violent clampdown on supporters of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood movement, in which hundreds died. Namira publicly opposed the violence and the state’s abuse of the protesters’ freedoms, which went against public sentiment at the time.

Namira’s third album, released in 2014, saw him move away from his previous optimism into darker territory. The album’s first single, ‘Esmaani’ (‘listen to me’), reflected the frustration of the youth who had seen the gains of the revolution rolled back in less than a year. The song criticized the older generation, who blamed the youth for instigating and leading the revolution.

“We cannot live without hope, but there are massive challenges that my generation and I face that cause us serious frustration. Our hopes were so high, but the reality was very different,” Namira said in an interview with Deutsche Welle Arabic.

Other songs on the album discuss oppression, corruption and the despair of young people who began to leave Egypt in droves, leaving behind families and loved ones to seek a better life elsewhere or out of fear of prosecution.

In the same year, Egyptian state radio banned Namira’s songs for criticizing the authorities. Abdel Rahman Rashad, the state radio’s chairperson, sent a memo to all radio stations ordering them not to play any of Namira’s songs because he called Morsi’s ouster a military coup. Rashad told the BBC in an interview that no artist who criticizes the government should be given airtime.

“I have said over and over that I do not belong to the Muslim Brotherhood, but anyone who believes I am will never listen,” Namira told Deutsche Welle Arabic. “I’m probably the only artist who was accused of this and can’t get rid of it.”

In 2015, reports emerged that Namira had also been banned from the Egyptian Syndicate of Musical Professions. On Twitter, he thanked the syndicate and everyone who had stood by him, and said he would continue to perform the art he loves. He gives concerts around the world and supports several worthy causes such as Humanic Relief, a Vienna-based aid organization that assists people, particularly children, in need. However, he currently has no scheduled appearances in Egypt.

This has not stopped young people from listening to his music. He is still one of Egypt’s most popular artists, and songs from his latest album have received over 80 million views on YouTube. While he may have been banned from the airwaves, he has used social media to stay in touch with his fans, and unlike other mainstream artists, he continues to voice his support for the revolution.