Surrounded by regional powerhouses like Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran, there could always be someone after your oil. That is the sentiment of many Kuwaitis, with some of them even using the word ‘monsters’ rather than ‘powerhouses’.

Perhaps it is post-Iraqi invasion paranoia. After all, the invasion by Saddam Hussein in 1990, was (among other things) about oil. Iraq accused Kuwait of producing over its OPEC quota and of slant drilling across the border. After being defeated by the international US-led coalition in February 1991, Iraqi forces withdrew from Kuwait but not before setting more than 600 oil wells on fire.

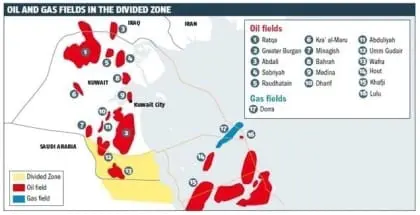

Iraq is not the only neighbour with whom Kuwait has quarrelled about oil. Saudi Arabia and Iran are both causes for concern. In recent months, the situation has turned particularly sour in the Divided Zone (also known as the Partitioned Neutral Zone, PNZ).

In 1922, the boundaries between what is now Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were demarcated, leaving a neutral zone between them. However, the land was of no particular interest to anyone. Borders did not matter; tribes were only loyal to their leaders and roamed across the desert according to the needs of their flocks of sheep and camels.

That was until oil was struck in the late 1930s. Negotiations began and, in 1965, an agreement was reached to divide the zone equally between the two countries. The adjacent maritime zone was demarcated in 2000. Under the agreements the natural resources are shared equally and concessions are granted by both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. So, even if the biggest part of an oilfield is on the Saudi side, for instance, production is shared 50/50.

Why a neutral zone, and not a simple division of the land? Because oil cannot or may not always be extracted right above its sub-soil location. If the zone had been cut in half, Kuwait could have siphoned oil from the Saudi side, and vice versa. Hence a neutral zone, with a joint operation between Chevron (for the Saudis) and Kuwait Gulf Oil Company.

Sounds easy, but it isn’t, at least not from an international law point of view. The legal status of the PNZ is unclear. On the one hand, the zone has a separate identity, on the other – apart from the natural resources – each country has full sovereignty over its side.

For example, people working on the Kuwaiti side are required to obtain their visa and work permits from Kuwait, regardless of whether they are working for Chevron or Kuwait Gulf Oil Company. Kuwait can stop issuing these permits and also order Chevron to move its offices out of Mina al-Zour, the port town through which the crude is exported. It recently did both, which led to a halt of production in the Wafra fields.

The reasons for the Kuwaiti obstruction remain unclear, although industry sources have said that Kuwaiti authorities were unhappy with Saudi Arabia for renewing a 30-year agreement with Chevron in 2009 without consulting them. Chevron holds a lease on a piece of land where Kuwait plans to build a new refinery, an issue that stems from 2007.

It is not the only row over shared fields. In 2013, plans to develop the Dorra gas field were shelved because the two countries could not agree on how to share the gas back on land.

The Dorra field has also long been a bone of contention between Kuwait and Iran. Part of the field lies on a disputed part of the continental shelf, which is shared by Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Iran. When Iran announced an investment plan for what it considers its side of the field, Kuwait immediately summoned the Iranian envoy and handed him an official protest.

In general, and probably not entirely unrelated to the Dorra issue, the Kuwaiti-Iranian relationship is deteriorating, with Kuwait accusing Iran of supporting Hezbollah sleeper cells in Kuwait.

Meanwhile, Imam Hussein TV, an Iraq-based Shia television channel, reported that Saudi Defence Minister and Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman had threatened to go to war with Kuwait over the oil disputes, claiming Saudi Arabia has historical rights over the fields. It is familiar rhetoric to the Kuwaitis, who heard Saddam Hussein make similar statements more than 25 years ago.

However, it is unknown whether Bin Salman actually made the threat. The sources are vague and the report may have been an Iranian attempt to drive a wedge between its archenemy Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. On the other hand, Bin Salman’s aggressive military tactics in Yemen suggest that he may want to frighten Kuwait enough to keep it in check, without necessarily risking a conflict at this point.

After all, the Saudis need their Gulf Cooperation Council allies in their war in Yemen, which is quickly becoming a disastrous enterprise. It also seems unlikely that Riyadh would incur the wrath of its most important ally, the United States, which is backing the Saudis in Yemen but would not support a war against Kuwait.

In any event, Kuwait has good reason to be wary of its neighbours, although news reports about oil-greedy neighbours should be viewed with caution. This is not only because one neighbour may try to slander the other, but also because Kuwait may have an interest in scaring its own people.

Focusing on the bad guys over the border has the advantage of steering the attention of the oil-thirsty population away from the Kuwaiti oil sector’s biggest problem: paralyzing internal politics.