This article discusses Turkey's interests in Syria and how it balances its actions while dealing with various major players, including the US, Russia, Iran, and Israel.

Hussein Ali Alzoubi

Like a rope dancer, Turkey manoeuvres and balances its steps for its agenda in Syria. As current circumstances have become complex in North Syria, Turkey is hanging onto all influential forces, including the US and Russia, not to upset its balance.

After two months of discourse threatening a “potential” Turkish military ground operation in Syria, the Turkish dialogue approach prevailed. Recently, there have been talks about normalising relations with the Syrian regime through Russian mediation. The Turkish defence minister met his Syrian counterpart in Moscow in late 2022.

Yet, both approaches serve a mutual purpose: ending the Kurdish issue on the southern Turkish borders, one of the most sensitive national security matters.

The regime and the opposition in Turkey are on the same page regarding the Kurdish situation. They both fear that it will lead to a division of the country at the hands of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and its military branch, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which in turn is considered a wing of the PKK by Ankara.

Turkey has to deal with significant players that deeply clash strategically while addressing this issue. Turkey has to consider the US, the SDF’s primary sponsor, and Russia, the Syrian regime’s incubator, both of which have forces on Syrian soil. Moreover, Turkey cannot afford to neglect Iran and Israel’s role in the conflict in northern Syria.

Conflict of Major Interests

Due to the Russian war on Ukraine, the region’s geography has become part of a highly polarised landscape.

Turkey knows that the US is the most influential over the SDF and can change the reality in northern Syria. Hence, Ankara uses all its cards to elicit Washington’s support for the Turkish vision.

Turkey played its first card when it objected to Sweden and Finland joining NATO. The second card comprised Turkey’s rapprochement with Russia in the middle of a major face-off between Moscow and Washington in Ukraine.

According to the Syrian political researcher Kamal al-Labwani, Washington would choose Ankara over the SDF. The reality, however, seems different, as the US has numerous economic and political instruments it can use to exert pressure on Turkish leadership and internal affairs, such as the F-16 fighter aircraft deal. These cards that the US holds might turn the tables in the coming Turkish elections and change the country’s political map entirely.

On the other hand, Turkey should avoid upsetting Moscow since Russia can strike northern Syria’s heavily-populated opposition areas, especially Idlib and Aleppo’s countryside. This could potentially expose Turkey to another refugee wave at a time when the matter of Syrian refugees has become paramount in the coming elections. Moreover, a military operation without Russian consent would place the Turkish forces in a military confrontation with the Russians.

At the same time, Russia does not want Turkey to side with the West in its battle in Ukraine and therefore seeks an approach to push Turkey to normalise relations with Damascus.

Iran, another major player in Syria, was stunned by the Syrian-Turkish rapprochement. According to Asharq al-Awsat newspaper, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, the Iranian foreign minister, complained about the news of Syrian-Turkish meetings in the media. Tehran seems to object to the rapprochement as it has refused to supply oil to the Syrian regime unless paid in advance.

Also, it postponed the visit of Ebrahim Raisi, the Iranian president, to Syria indefinitely. As a result, Iran seemingly got what it wanted as Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, later announced Iran’s participation in the talks between Syria, Turkey and Russia.

Militarily, according to several sources, such a rapprochement is not in Iran’s favour, especially since it would entail the targeting of the PKK, which is, unofficially, on good terms with Tehran. Additionally, a Turkish military operation stretching 30 kilometres deep along the border, whether joint or unilaterally, would mean a diminishing role for pro-Iran militias in the region.

Politically, Iran will not simply give up its gains in Syria. Iran has a solid military presence in Syria through its militias. It also changed Syria’s demographic map to serve its agenda. Nevertheless, Iran is keen on bringing al-Assad back to international diplomacy as no other country has been able to match what he has offered Iran.

Concurrently, Iran wishes to have a “good” relationship with Turkey. Hence, Iran seeks to be represented in any settlement between Turkey, Russia and Syria. In this regard, Ali Asghar Khaji, the Iranian foreign minister’s senior advisor, said, “The Syrian crisis cannot be resolved easily without the presence of Iran.”

Iran’s presence in Syria ultimately involves Israel, especially since Netanyahu’s return to power. Netanyahu’s government will undoubtedly support any move that curbs Iran’s presence in Syria, directly or indirectly.

Reality On Ground

Even though major strategies are defined in the corridors of decision-making capitals, their enforcement is linked to the conditions imposed by on-the-ground reality. To envision what might happen, we must return to 17 October 2019.

At the time, Mike Pence, the former US vice president, announced that the US and Turkey had agreed to terminate the Turkish military operation “Peace Spring” to secure the withdrawal of the Kurdish-majority SDF from a safe zone that Turkey proposed to establish on the borders with Syria.

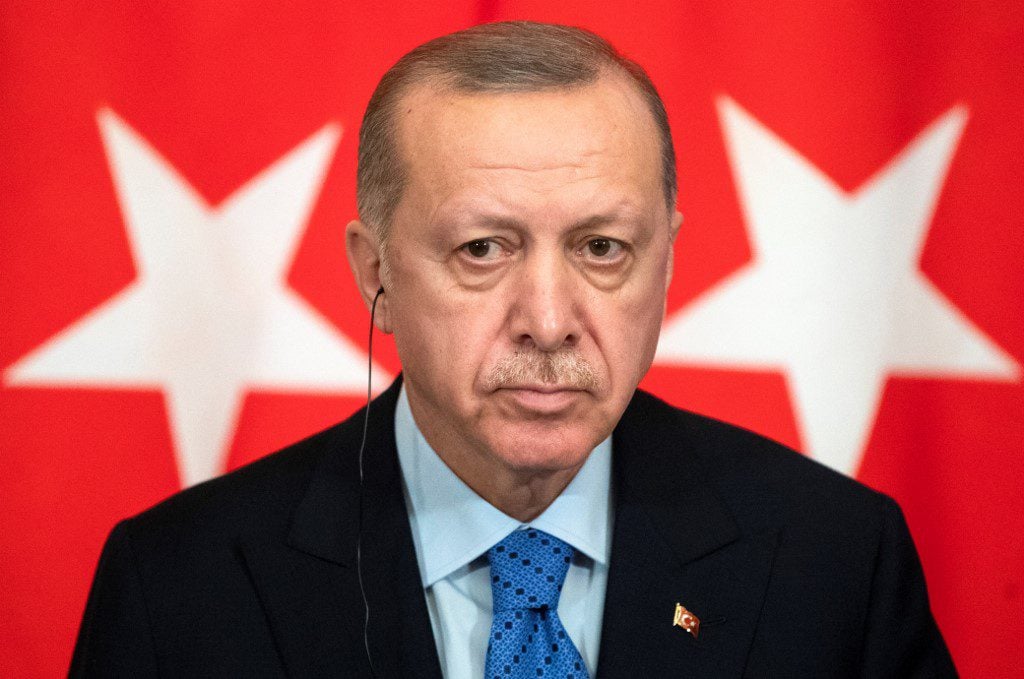

On 22 October 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan agreed that the YPG, which is an important part of the SDF, would retreat 30 kilometres from the border. Moreover, the YPG would withdraw from Tal Rifaat and Manbij. Under the agreement, the removal of Kurdish fighters would be facilitated by Russian military police and Syrian border guards.

It is worth noting that, unlike the agreement between Ankara and Moscow, the deal with Washington concerning a safe zone did not indicate a 30-kilometre distance. The deal only mentioned the withdrawal from a safe zone.

The Turkish operation, in which the opposition’s Syrian National Army (SNA) took part, resulted in control over Ras al-Ayn, Tell Abyad and the areas stretching from there until the Euphrates. The operation’s forces reached the M4 highway and captured an area of 4,000 square kilometres.

A year after the operation, Turkey announced that the number of residents who returned to the safe zone reached 200,000. In May 2022, Erdoğan announced that around 500,000 Syrian refugees had returned to Syria’s “safe zones.”

Whether in relation to military operations or rapprochement with al-Assad, current official Turkish discourse focuses on Syrian refugees. For security reasons, the focus is increasingly directed towards the Qandil Mountains north of Iraq, the stronghold of the PKK fighters.

Turkish and Syrian Interests

From an economic perspective, al-Assad cannot afford the return of refugees. Returning to the “safe zones” and Idlib seems impossible, given the population density in these areas. At the same time, the return of millions of Syrians to their home regions would mean the failure of all Iranian-sponsored schemes to bring about demographic changes.

However, most refugees are firmly determined not to return to life under the regime’s tyranny. The Lebanese refugee experiment proves the inefficiency of an approach focusing on voluntary return, in particular when considering that refugees are relatively better off in Turkey than in Lebanon unless Turkey were to adopt a system of forced deportation. In this case, Ankara would lose its morality, its opposition allies and its popular base.

In its last statement concerning Turkey, the Syrian regime announced that its condition for improving relations with Turkey is for Turkey to “end the occupation.” Damascus knows Ankara will not “end the occupation” unless it yields more.

In this context, al-Labwani believes that, similarly to the Iranian and Russian presence, legitimising the Turkish military presence is al-Assad’s best shot. This would provide increased freedom to the Turkish forces in Syria while the regime would uphold the appearance of managing its operations.

What does Damascus want? In an article published on the website of the pro-regime channel al-Mayadeen, Ziad Ghosn, a Syrian journalist, argues that Damascus intends to regain absolute control over Idlib, which could be executed in several phases. The regime might, for example, first take control of the road between Aleppo and Latakia before gradually seizing one city after another.

The Syrian Arab Army might accept to incorporate some of the opposition’s militias into its structure, but only as reserve units. Ghosn ruled out a scenario similar to what happened in Daraa since the factions will have handed over their heavy weapons.

Consequently, and in light of the potential agreement with Ankara, he believes that the regime will likely carry out a limited operation to eliminate Tahrir al-Sham, the faction controlling Idlib.

Look for Washington

The potential rapprochements, however theoretically feasible they may seem, are far-fetched without the US’ green light.

The Hudson Institute considered three scenarios for responding to the situation in Syria. The first would comprise the US’ withdrawal from Syria. Unless the US is willing to give up its 20 fully-equipped bases and checkpoints in northern Syria, this scenario is, however, unlikely.

The second sees the US forces muddling through east of the Euphrates, instigating Turkey to work with Russia. If the US proceeds with this scenario, it will eventually negotiate its terms for withdrawal with Russia.

The third scenario is for the US to work with Turkey to build a Syria that serves the US and its allies.

According to Hudson’s report, the third scenario “makes sound geostrategic sense.” If it proceeds with this scenario, it seems unlikely for the US to abandon the SDF. The US, however, appears to be exploring other options to appease Turkey without losing the SDF.

According to sources, the US is attempting to approach the Arab factions in the SDF-controlled areas, which are mostly inhabited by Arabs.

Moreover, to end the marginalisation of Arabs in the SDF, US representatives have held meetings with the 17th Division, which is affiliated with the Free Syrian Army. The Division had control over Raqqah and clashed with ISIS several times. Since the SDF gained control over the region, the Division disappeared.

Ending the marginalisation of Arabs would allow some refugees to return to their SDF-controlled home regions. This could coincide with Turkish-US patrols 10 kilometres deep along the borders.

This last scenario has not been ruled out. Perhaps because Washington wants to avoid letting Putin score points for his ally, Bashar al-Assad. The US has recently issued the Captagon Act, which primarily targets al-Assad’s family. The White House has also repeatedly rejected and denounced the normalisation of relations with the al-Assad regime and emphasised compliance with Security Council Resolution 2254.

Lastly, the recent devastating earthquake that hit southeastern Turkey and northern Syria will delay Turkey’s activities in the short term. This, however, does not mean that Turkey will not pursue what it sees as favourable in such a vital region.