By: Sophia Akram

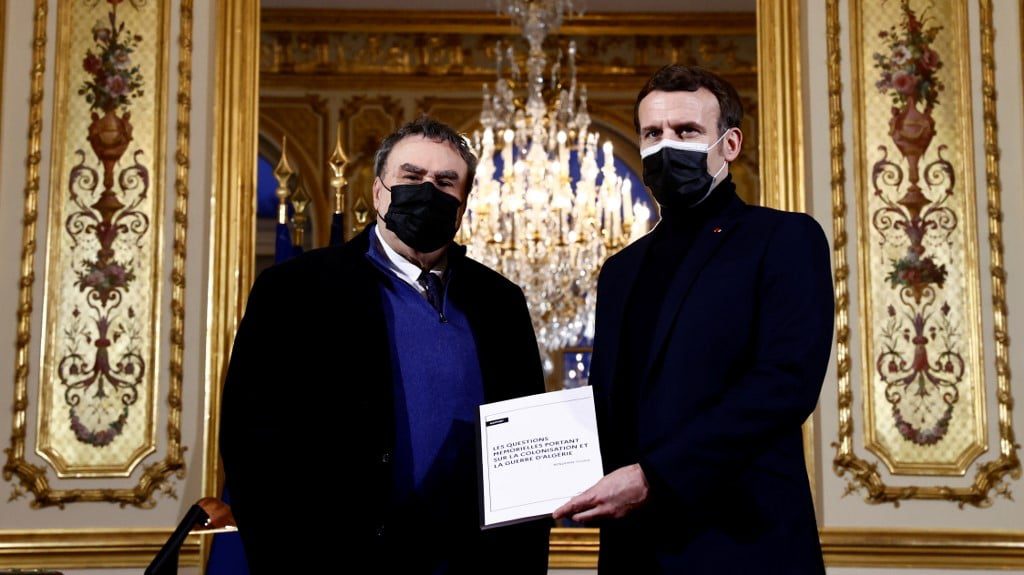

On Wednesday 20 January 2021, historian Benjamin Stora submitted his 160-page report to the Elysée on ways to move forward and heal from past aggressions after more than one hundred years of colonialism and a brutal seven-year war that ended in Algeria’s independence from France.

Commissioned in 2018, President Emanuel Macron wrote to Stora asking for help in sending a clear message of renewing ties with Algeria, whose significance to France is reinforced with its Mediterranean and Saharan border, and which he said would help settle problems with immigration and terrorism.

“The president wants these initiatives to allow our country to take a lucid look at the wounds of the past, to build, over time, a reconciliation of memories”, read the presidency’s statement on Wednesday.

The report is one of a number of efforts Macron has made to acknowledge France’s role in Algerian suffering, making him more progressive than other French leaders.

In 2017, during a trip to Algiers, he called colonisation a “crime against humanity” and later he acknowledged the systemic use of torture in the 1957-1962 Algerian War. This acknowledgement included the treatment of Maurice Audin, a French anti-colonial activist who was disappeared, tortured and killed, which he said was enabled by a “legally instituted system.”

The 43-year-old leader has, however, fallen short of apologising for colonisation and it bears no mention in the report, which could be a political move to balance two competing sentiments to the period with Macron receiving censure from the right and far-right for his apologetic gestures.

What Macron has done is placed Stora in charge of a “memories and truth” commission to oversee reconciliation in the form of commemoration.

Stora has mooted the commission be made up of various players “engaged in Franco-Algerian dialogue”, like Fadila Khattabi of the National Assembly, Karim Amellal, an inter-ministerial delegate to the Mediterranean, doctors, researchers, business people and association members.

Here are some of Stora’s recommendations that could be enacted.

Commemorations

France has already set 19 March as the remembrance day for victims of the 1954-62 Algerian war during President Francois Hollande’s presidency. Although, it was reportedly more as a diplomatic gesture to elicit support for an operation in Mali.

Other continued memorials include the tribute day of 25 September to Harkis — the Algerians that fought for the French side — and 17 October, concerning the repression of Algerian workers in France. It is proposed that Algerians are more fully associated with these commemorations with association or memorial group invited to attend.

The original date of 19 March came after much deliberation after the Evian accords that saw the end of the brutal war and while it seems symbolic, it is considered a step to reconciliation.

Other actions of acknowledgment could include an effigy of Emir Abdelkader, who fought against the conquest of Algeria by France, and recognition of the assassination of lawyer Ali Boumendjel, a leading figure in Algerian nationalism, killed during the Battle of Algiers in 1957.

Nuclear tests and mines

France carried out 17 nuclear tests in Algeria in the 1960s at sites with at least 20,000 residents. There has been some suggestion of an uptick in medical issues following the blast. During the war, France also laid mines at the border, yet to be fully cleared. Recommendations include investigating the consequences of nuclear sites and continuing the clearance of mines at the border. Around nine million mines were planted during the war, which resulted in 7,300 victims, many of which require continued health and social care.

The nuclear testing and landmine operation is a tangible example of the lasting legacy of the war.

Harkis

Harkis were volunteer Muslim Algerians who served as auxiliaries for the French in the Algerian War, which many of them did under duress of economic hardship. France did award the highest civilian honour, known as the légion d’honneur, to veteran Harki fighters but this was thought insufficient considering their plight. Thousands of these fighters were abandoned after the war and accused by Algerian nationalists of treason — many were massacred. Around 82,000 ended up in France but were not met with open arms by the French people, and they lived in difficult conditions. An annual tribute day was only given to the Harkis from 2001, almost 40 years after Algerian independence.

The recommendation in the report is to help facilitate the movement of former Harkis between France and Algeria as some older generations have expressed a desire to return.

Archives

Another recommendation Stora made is to initiate a joint working group on archives, set up after Hollande’s 2012 visit, and which had stopped meeting from 2016. Stora says the working group on archives should take stock of the inventory of archives taken by France and left by France in Algeria, allowing Algeria to part recover these historical records with consultation by French and Algerian researchers; a common archive resource accessible to both countries was also proposed. The impact of this endeavour could be far-ranging, impacting policy and diplomacy as well as unearthing technical information in the form of maps. In some ways, recovering the archives is a matter of retaining heritage and shining a light on pre-French rule.

The disappeared

While there are stories of Algerian disappeared from the civil war of the 1990s, there is also a legacy of those missing in relation to the 1957-62 conflict. There are estimates of thousands of these disappeared persons, and a working group was set up from the 2012 agreement between Hollande and Algeria’s government to find the graves of those disappeared — Algerian and French — during that war. Stora recommends progressing on this work, an important part of seeking truth and reconciliation. Some researchers think there could be survivors.

Some also say it is important for Europeans to realise that the French perpetrated atrocities associated with “exotic” regimes, not in the too distant past.

Further recommendations that Stora could take forward under the commission include collecting witness testimonials; studying the human remains of combatants; setting up a commission into kidnappings and assassinations; preserving Jewish and European cemeteries in Algeria; incorporating prominent Algerians into street naming in France; facilitating research visas; doing publishing and translation work relative to the period, and incorporating colonisation in the school curriculum. Other recommendations involve increasing exposure of France’s harms on its former colony.

“If you lift all these lids one after the other, you end up with a real overview of the history of colonization”, said Stora, in relation to the report.

While the report has been well-received generally, this has been somewhat overshadowed by the omission of an official apology. French legal academic who looks at human rights and civil liberties in France, Europe and North America, Rim-Sarah Alouane, said: “Oh well the honeymoon did not last for too long. How one can expect reconciliation when you don’t start with apologizing for the crimes your country committed for years?”

Agence France Presse also reports discontentment among the Algerian diaspora in France.

“France must recognise its crimes, the murders, the torture and the forced displacements of the Algerian people,” said 26-year-old university student Hichem Lahouidj to the French wire service, “French colonialism was one of the worst”.

Day labourer Abdi Noureddine said France wouldn’t apologise for fear of paying “hefty financial compensation”.

President Abdemadjid Tebboune reportedly said, “We have already had half-apologies. The next step is needed… we await it”.