Introduction

After the fall of the dictatorship of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, the regime of governance in Tunisia witnessed a transitional phase, during which the first democratic public elections were conducted for the National Constituent Assembly on October 23rd, 2011. And in the light of the results, a consensus government was formed under the leadership of the Prime minister Hamadi Jebali in December 2011.

The newly elected government included ministers from three parties: the Ennahdha Party (or Renaissance Party), The Congress for the Republic, and the Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties. At the same time, Moncef Marzouki was elected as President of the Tunisian Republic.

In 2013, in the aftermath of the assassination of the left-wing opposition leader Chokri Belaïd, Tunisia witnessed unrests on the political level, which pushed the Ennahdha Party, the one with the largest number of representative seats, to form another government under the leadership of a new Prime minister, Ali Laarayedh, from the Ennahdha Party.

And after the adoption of the new constitution of Tunisia by the Constituent Assembly in January 2014, new legislative elections were organised and the Nidaa Tounes party (Call of Tunisia) won the majority of votes. A new government was formed under the leadership of Habib Essid, an independent politician.

At the end of 2014, Beji Caid Essebsi, the chief of the Nidaa Tounes party, was elected as the new President of Tunisia. And since August 2016, Youssef Chahed, from the Nidaa Tounes party, has been the Prime Minister of Tunisia, leading the Tunisian government.

Political Parties

Demonstration in 2011 against RCD party members associated with the former Ben Ali regime, taking part in the interim government after the January 2011 revolution / Photo HHCongress for the Republic (CPR)

The CPR, a secular centre-left party, was created in 2001. Tunisia’s previous President, Moncef Marzouki, a physician and human-rights activist, was one of its founders. The CPR was banned in 2002 by Ben Ali, a decision that led Marzouki to go into exile in France, from where he continued to lead the CPR clandestinely.

Following the revolution, Marzouki returned to Tunisia, and the CPR became legally recognized to participate in the Constituent Assembly elections, from which it emerged as the second strongest force, after Ennahda, with 8.7 percent of the vote and 29 of the 217 parliamentary seats.

Moncef Marzouki was consequently appointed President of Tunisia, which has led to much friction with the Prime Minister of the ruling Ennahda, Tunisia’s strongest political party, which the CPR and Ettakatol (also known as the Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties, founded in 1994) joined in a coalition.

Ennahda (Renaissance)

The Ennahda party has its roots in Tunisia’s 1960s Islamist movement, which was then called al-Jamaa al-Islamiya, a loosely organized Islamic platform that attracted many traditional Muslims who did not identify with the modernizing and Westernizing policies of the secular ruling elite of the Bourguiba regime.

Operating initially in secrecy, al-Jamaa al-Islamiya was discovered accidentally in 1980 by the regime. Upon its discovery, the Islamist movement applied for a license, in order to be officially recognized by the regime as a political party, and it changed its name to the Islamic Tendency Movement (MTI).

While there was occasional rapprochement between the Islamists and the secular ruling regime, Bourguiba and Ben Ali both decided to suppress and violently confront the Islamists, the major opposition force in the country and hence the primary threat to their autocratic rule. Consequently, many members of the MTI – which was renamed Ennahda (Renaissance) in 1989 – were either imprisoned or forced into exile under the former regimes, leading many observers to declare the movement dead from the early 1990s.

Only with the advent of the Tunisian revolution did Ennahda re-emerge on the political scene. As a party that has never failed to criticize the previous autocratic governments, it enjoys legitimacy in the eyes of many Tunisians who opposed the earlier secular rule. It was therefore no surprise that the party emerged from the 2011 Constituent Assembly elections as the most important political actor.

This was also due to the organizational capacities of Ennahda which other parties could not match. Ennahda’s platform envisages the advance of Islamic principles and traditions in Tunisian society while maintaining the country’s strong socio-economic ties with the West. It also advocates enhanced relations with other countries such as Turkey and Qatar.

The Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties (Ettakatol)

Founded in 1994 by its current secretary general Mustapha Ben Jafar, a radiologist and political activist, Ettakatol, a secular centre-left party, was not legalized until 2002. Given the limitations on the opposition during the autocratic Ben Ali regime, however, the party played only a minor role before the Tunisian revolution. For example, Ben Jafar attempted to run in the 2009 presidential elections, but he was disqualified by the government. Following the Constituent Assembly elections, Ettakatol emerged as the fourth strongest force. It joined Ennahda and the Congress for the Republic (CPR) in a coalition government, with Mustapha Ben Jafar as the head of the Constituent Assembly, which is tasked with writing a new Constitution for the country.

According to the official web site of the party, Ettakatol’s main goals are ‘the improvement of the political climate, legislative review, the separation of the apparatus of the ruling party and the state machinery, the organization of free elections, the rebalancing of the state powers, the exercise of fundamental freedoms, and the respect for human rights’.

The Popular Petition for Freedom, Justice, and Development (al-Aridha)

Al-Aridha was formed after the Tunisian revolution as an electoral list by Mohamed Hechmi Hamdi, a London-based journalist and media figure. It is not an official party, even though it is closely linked with the Party of Progressive Conservatives (PPC). Its leader Mohamed Hechmi Hamdi is a former member of the Ennahda party, from which he split in 1992. In subsequent years he allegedly entertained close relations with the Ben Ali regime. When he founded al-Aridha in 2011, he used his television channel al-Mustakilla to promote his cause. His talk show ‘Hiwarat Tunisiya’ (Tunisian Discussions) was an important means of responding to personal requests and comments from Tunisian citizens, who were often promised a better life if they agreed to vote for al-Aridha.

Hechmi Hamdi’s widespread media networks, which quickly disseminated the Petition’s populist message, contributed to al-Aridha’s success in Tunisia’s Constituent Assembly elections. Among other things, the party promised a grant of 200 Tunisian dinars to each of Tunisia’s approximately 500,000 unemployed, as well as free health care. Hechmi Hamdi even claimed that he personally contributed 2 billion Tunisian dinars to the national budget. Currently, the name of al-Aridha became the ‘Current of Love’.

Progressive Democratic Party (PDP)

Founded in 1983 as the Progressive Socialist Rally, the secular left-wing party was recognized legally only in 1988. In 2001, it changed its name to the Progressive Democratic Party (PDP). Before the Tunisian Revolution, the PDP, like all political opposition forces under Ben Ali’s regime, had little power. During the 2011 electoral campaign, many observers expected the PDP to emerge as one of the most important parties in the 2011 Constituent Assembly elections, given its apparent legitimacy as a traditional opposition party to the former regime. When the party came only fifth, receiving just seventeen seats in the Constituent Assembly, many inside and outside of Tunisia were surprised.

Many factors contributed to the unexpectedly poor performance of the PDP in those elections, including a poor electoral campaign in Tunisia’s remote areas and the split of the secular-left vote amongst several parties and independent lists. Also, the PDP’s explicit rejection of many Islamic values offended many religious Tunisians. In April 2012, the PDP merged with other secular parties into the Republican Party, hoping that a more unified secular left-wing political front would result in a stronger voice in upcoming elections.

Nida Tounes

Nida Tounes (The Call for Tunisia) is a secular opposition party that was founded in July 2012 by the current Tunisian president Beji Caid al-Sebsi. The party has extremely opposed the troika government ruling coalition and declared Tunisia’s Constituent Assembly, tasked with writing a new Constitution, ‘illegitimate’ for having failed to finalize the Constitution within one year, the limit decreed by Tunisia’s former interim President. Nida Tounes party (Call of Tunisia), enjoyed the largest representation in Parliament after the 2014 election, with 86 seats.

The Judiciary

The Tunisian legal system is rooted in both the French civil-law system and Islamic law. While formally independent under the Ben Ali regime, the judiciary was under the de facto control of the Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature, the members of which were appointed by the President.

The Conseil Supérieur was tasked with appointing and promoting lawyers, as well as taking disciplinary action. Consequently, practising judges were linked closely to the President, undermining the independence of the judicial system. Criminal judges, in particular, were restrained by having to undertake judicial proceedings against political dissidents, often violating international human-rights standards.

The lack of independence of the judiciary is further illustrated by the fact that, in 2005, the Association of Tunisian Judges, an independent judicial institution, saw its leadership replaced by lawyers close to the regime. The dismissal of the leadership followed their critical statements about the government, and they were subsequently harassed and discriminated against in their professional life. Worsening human-rights conditions in the mid-2000s can be explained partly by the decreasing independence of the judiciary, as this led to unfair judgements and to breaches of major human-rights conventions.

In spite of the lack of independence of the judiciary under the former regime, Tunisian judges have been praised for their professional standards in fields such as labour, property rights, and the economy, thereby facilitating foreign investment in the country. Compared with other countries in the region, Tunisian lawyers espouse a relatively modern interpretation of civil law in fields such as women’s rights.

Nonetheless, with the start of the Tunisian revolution, judges were quick to stand up against the regime, protesting their lack of independence and the omnipresent high-level corruption. Following the revolution, many judges close to the former regime were dismissed, but the criteria for the dismissal of judges was criticized as biased.

The Tunisian justice system continues to face major challenges, with many secular Tunisians, in particular, criticizing a return to a more traditional judicial system that is increasingly characterized by elements of Islamic law. Trials have been held for blasphemy and ‘indecency’.

This is despite the fact that Sharia law does not constitute an official source of legislation. Indeed, although Ennahda initially wanted to include a reference to the Sharia in the Constitution, the opposition was against it and eventually Ennahda decided to drop the clause.

The Presidency

Under Presidents Habib Bourguiba and Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisia was governed by its 1959 Constitution, which was revised several times in the 2000s. The Constitution stipulates a semi-presidential system, with a bicameral Parliament. The government is appointed by the President.

Whilst the 1959 Constitution stipulated the separation of powers, the President became, under the regimes of Bourguiba and Ben Ali, the dominant political figure: he exercised great control over the other branches of government. The combination of presidential hegemony, the broad powers attributed to its political arm, the Constitutional Democratic Rally (Rassemblement Constitutionel Démocratique, RCD) party, and the pervasive security forces controlled by the regime, undermined any effective control over the President by opposition forces.

Under the 1959 Constitution, the government was accountable only to the President and not to the Chamber of Deputies (Parliament). The Constitution stipulated that, rather than controlling the executive branch, the Parliament was to evaluate whether the government’s policy conformed with the President’s policy. Even though a 1976 amendment empowered the Parliament’s lower house to dismiss the government through a vote of no-confidence, a 2002 amendment required a two-thirds majority for this action.

This rendered this stipulation effectively meaningless, as the majority of seats were held by Ben Ali’s RCD party; following the 2009 elections, for example, the RCD controlled 75 percent of parliamentary seats.

The legislative functions of the Parliament were further limited by the President’s power to rule by decree in most areas. Moreover, in 2005, Ben Ali founded a second chamber, the Chamber of Councillors, some of whose members were named by the President himself, making the Parliament largely a rubber stamp for presidential decisions. This was also true for the executive, headed by the Prime Minister, who was mainly a figurehead tasked with executing presidential policies.

The New Order

Since the Tunisian revolution and especially following the October 2011 elections, the balance of power between the various state entities has shifted in favour of the previous Prime Minister Ali Laarayedh, of the Ennahda ruling party. The previous President Moncef Marzouki of the Congress for the Republic (CPR), enjoyed less power, and his decisions have, in several cases, been overruled by the Prime Minister, causing friction within the previous ruling coalition.

With the drafting of a new Constitution, the future of Tunisia’s political system is still to be settled. Ennahda demanded for a parliamentary system, while other parties referred a presidential or semi-presidential system. After the ratification of the new constitution of Tunisia in 2014, the executive authorities were distributed between the President and the President of the Ministers/Prime Minister.

The Military

The (now retired) chief of staff of the Tunisian Armed Forces General Rashid Ammar, during a mass protest in January 2011 / Photo HH

With rising militant activity in Tunisia, the country’s leadership and fighting capabilities have been put to the test.

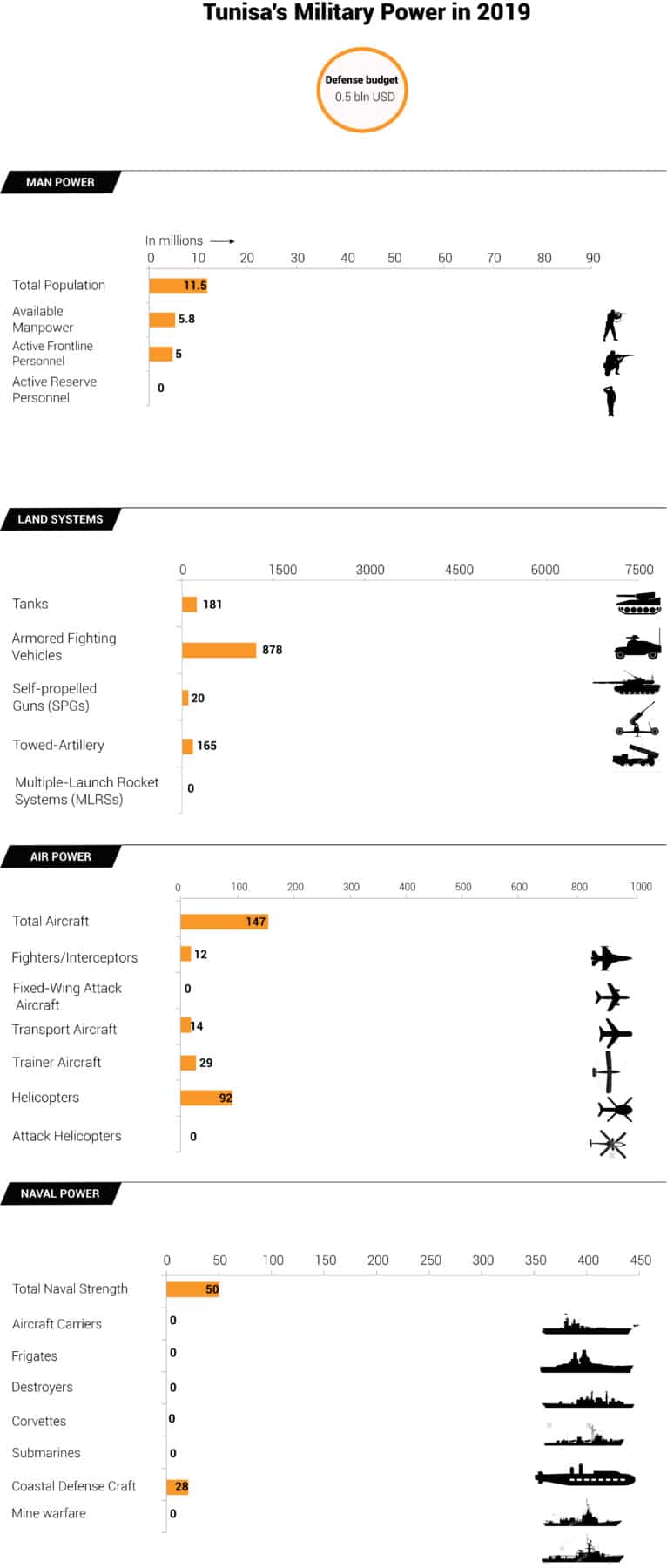

In 2019, Tunisia9a ranked 80 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 201,248 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $550 million. In 2018, military expenditure accounted for 2.1 per cent of GDP, compared with 2.1 per cent in 2017 and 2.3 per cent in 2016, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 36,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 36,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 155 | 60 |

| Fighter aircraft | 12 | 85 |

| Attack aircraft | 12 | 64 |

| Transport aircraft | 14 | 41 |

| Total helicopter strength | 88 | 43 |

| Flight trainers | 29 | 57 |

| Combat tanks | 199 | 61 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 985 | 54 |

| Rocket projectors | 0 | 137 |

| Total naval assets | 50 | - |

Tunisia’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

The Tunisian National Army, formed in 1956, numbers approximately 27,000. Compared with other countries in the region, such as Algeria and Egypt, the Tunisian army has traditionally played only a minor role in politics. This is a direct consequence of the 1962 failed military coup against then President Bourguiba, who, to counter the planned coup, imprisoned or executed key army leaders. And in 1968, Bourguiba put the parliamentary National Guard, a civilian force, in charge of monitoring the Army.

When Ben Ali took power in 1987, he continued and reinforced Bourguiba’s strategy of marginalizing the Army. While Ben Ali was himself originally from the military, he progressively weakened the Army in what he thought would enhance his own iron grip over the country. For example, he drastically reduced the size of the Army, and many of its members were imprisoned or had to quit their jobs for allegedly being Islamists or, in 1991, for planning a military coup, an allegation the military fiercely denied.

Many officers, frequently the most capable, were forced to retire. The role of the military was limited strictly to the defence of the country, improving the economy, participating in UN peacekeeping missions, and responding to natural disasters.

Ironically, the strategy that was meant to marginalize the military and empower the Ben Ali regime became, in the end, self-defeating. Hence, when protests broke out in Tunisia in December 2010, the military was quick to side with the protesters. The Army was eager to support the toppling of a regime that for decades had curtailed its power and influence. Since the Tunisian revolution, the military, whose structure remained unchanged, has resumed its activities. The Army has assisted Tunisia’s democratic transition by supporting the elections and backing the new government but never by involving itself directly in politics.

In May 2016, Tunisia signed a $101 million deal with the United States to purchase 24 Bell OH-58D Kiowa Warrior helicopters, an AGM-114R Hellfire missile, the high-accuracy APKWS missile system and the M260 rocket-launching platform. A deal worth $38 million dollars was also signed with Sikorsky to purchase four UH-60M helicopters.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Tunisia’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: