The Circassians, a mainly Muslim minority expelled from Russia during the Tsarist period is, all over the world, trying to reclaim its heritage. Exiled to countries including Turkey, Syria, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and the Balkans, the group is vying to carve out and retain a distinct Circassian cultural identity that has political implications.

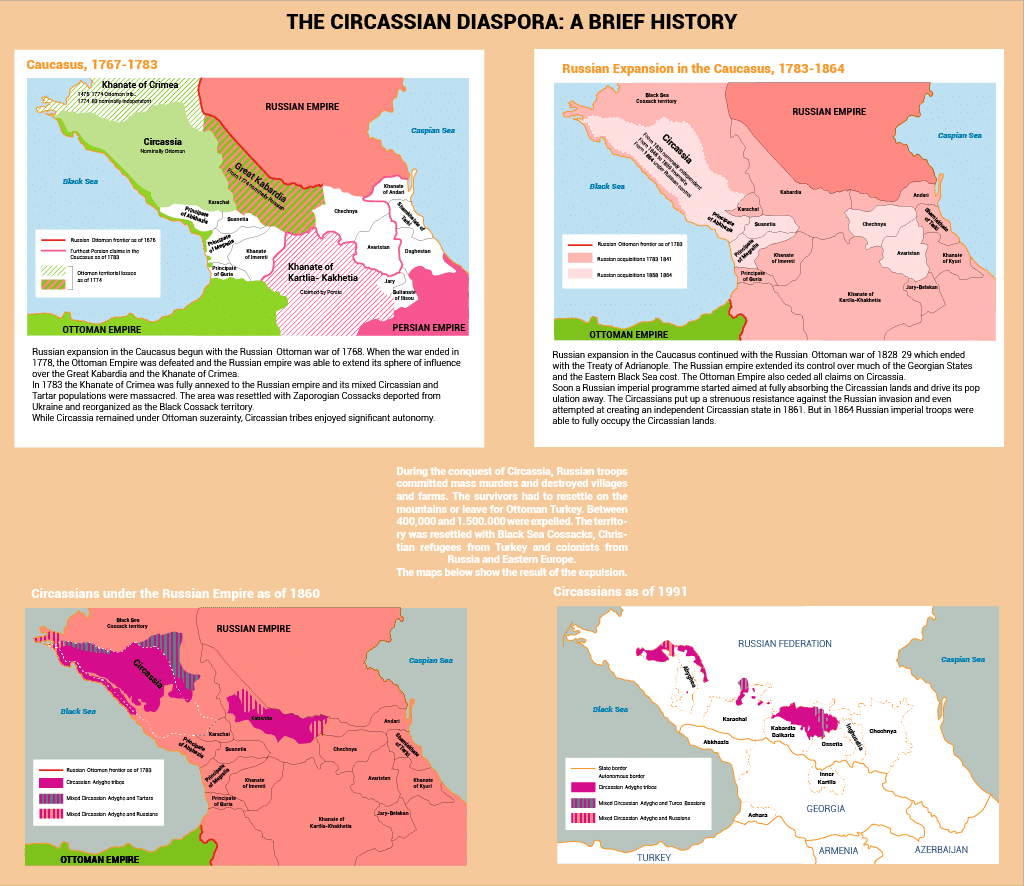

The 155th anniversary of the Circassian genocide in 2019 was a reminder that between 6 March and 21 May 1864, Imperial Russia oversaw the massacre of 400,000 Circassians and forcible exile of 4 million, leaving only 50,000 in their homeland. Although that number has since risen to almost 400,000, oppression of the Circassians continued until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It was at this time that the idea of a unified Circassian identity was reignited, although nationalist sentiment emerged during the early 19th century when Scottish diplomat David Urquhart designed a Circassian flag and, in the 1860s, different clans united in a failed attempt to petition the tsar to negotiate a peace treaty in Sochi.

In the 1990s, Circassian activism focused on eliminating the names of sub-ethnicities, instead proposing the term ‘Circassian’ for all members of the group.

While this failed too, it is apparent that the Circassian diaspora is keen to engage with and reclaim its heritage. This has manifested in interesting ways, from adapting traditional fashion for the modern era to attempting to establish or retain the distinct Circassian identity of towns where they live. For instance, the council head in Kafr Kama, a Circassian town in northern Israel, recently tried to enforce a declaration that the town should not allow non-Circassians to build homes in the area, accompanied by a petition signed by around 1,200 people.

Residents posted the Circassian flag on their Facebook profile, while the hashtag #ImACircassianAreYou has appeared on various social media. Efforts to preserve the Circassian language have also emerged, as has heritage tourism, prompting many in the diaspora to visit Circassian areas such as Adygea in Russia.

However, some elements of the Circassian population believe adopting traditional practices is not enough and espouse more radical action, including a return to the ‘homeland’.

Repatriation of Circassians to Russia is not unheard of. However, strict quotas and lengthy procedures have made this complicated, according to Ahmed Kataw, head of the Iraq-based National Diversity Organization, deterring many from doing so.

“They are regularly denied documents or turned away at the border,” said Neil Hauer, a Canadian journalist and security analyst based in the Caucasus. “But in the absence of a total crackdown from the Russian side, there is still enough will from the Circassian diaspora to keep a repatriation effort ongoing on some level.”

The war in Syria has seen many Syrian Circassians returning to Russia. Although not official refugees, they have been able to acclimatize and find jobs with the help of NGOs, said Hauer.

Those with bigger ambitions would like Moscow to recognize the Circassian genocide and the displacement that followed. “[The government] doesn’t offer any compensation or facilities for the return of Circassians to their homeland,” said Kataw.

Each year, Circassians commemorate the genocide on 21 May, referred to as a ‘black day’. Memories of this tragedy and the deep resentment it caused is still central to the Circassian identity.

“There is a very strong desire among a significant part of the Circassian population…to see the three partly or entirely Circassian republics of the North Caucasus – Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, and Adygea – united into one republic,” said Hauer, which is the other idea considered more radical among Circassians who prefer to toe a more Russia-friendly line. “[Unification is] becoming a demand of Circassian activists and national movements, who are dismayed by policies such as last year’s reduction in status of native language education to a voluntary school subject.”

On 19 June 2018, the Russian parliament adopted a bill making education in 34 of Russia’s 35 official languages optional, limiting instruction in minority languages to two hours per week. Previously, regional governments determined how languages would be taught or applied in schools, and many would offer the first few years of primary education in their own official minority language, Hauer wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine. He noted that the bill was intended to suppress minority identity in the North Caucuses out of fear of ethnic nationalism, which, perhaps ironically, started to grow as discussion of the bill got under way.

Moscow sees any moves towards Circassian nationalism as a threat, even if the majority of activists stress their dedication to the Russian Federation, according to Hauer. “Any nationalist activism in the North Caucasus is inextricably linked in the Kremlin’s mind with Chechnya and separatism.” This, he added, leads to activists being harassed by security services and marginalized by strengthening those organizations that stick closer to the government line.

This fissure in Circassian circles prevents a truly unified movement. In Turkey, for instance, where the number of Circassians ranges between 130,000 and 3 million, depending on the criteria used, there are two main groups: the Federation of Caucasian Organizations of Turkey, better known by its Turkish acronym KAFFED, and the Federation of Circassian Associations or CERFED. While KAFFED retains a conservative outlook and is active politically, CERFED is more liberal in the religious sense and purportedly apolitical in nature, despite gaining ground under the ruling Justice and Development Party amid its attempt to appeal to Circassian voters. Both groups seek stronger links to the historic homeland although their approach differs. KAFFED emphasizes pragmatic relations with Russia whereas CERFED opts for more heated rhetoric.

Representatives of Circassian organizations that work officially in Russia do not advocate recognition of the genocide or the return of historical Circassian lands. However, the number of young people supporting this more radical idea is steadily growing. Activists feel that a figure who can mobilize this ‘patriotic youth’ would be able to lead a nationalist movement in the future. This movement has been aided by the internet as Circassians around the world have found each other through chat forums and similar.

Yet while geographically dispersed pockets of Circassians can now connect and organize, attempts to re-establish their identity and heritage are likely to remain largely symbolic unless they can overcome fierce political resistance.