The reconstruction of Mosul and other areas of Iraq decimated in the fight against the Islamic State (IS) has been proceeding at a crawl, hampered by donor fatigue, corruption and an inefficient state.

While international donors have, to some extent, been competing for influence in Iraq via pledges of reconstruction aid, the actual amount committed has been quite small and falls far short of what Iraqi government officials say is needed.

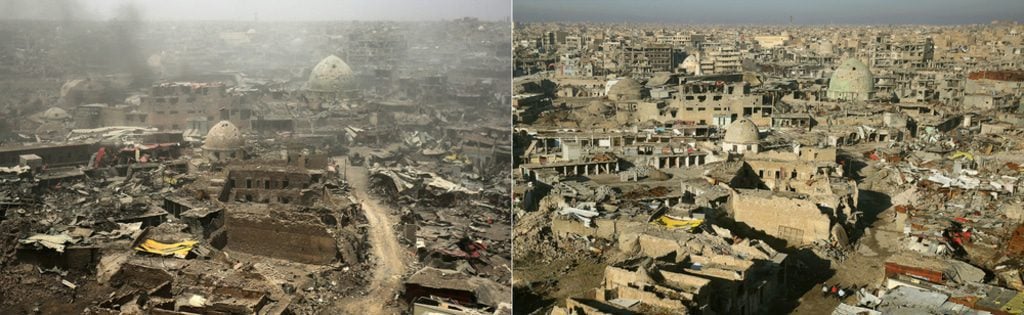

Mosul and other areas formerly held by IS were heavily damaged both by the extremist group and bombing campaigns by the US-led coalition fighting against it. The United Nations (UN) estimated that more than 40,000 homes were destroyed in Mosul alone, 2.3 million people remain internally displaced and hundreds of thousands more have fled to neighbouring countries. In west Mosul, restoring just the basic infrastructure is estimated to cost $700 million.

Yet since Iraq declared victory over IS in December 2017, rebuilding has moved slowly. Entire neighbourhoods in cities including Mosul, Fallujah, Ramadi and Sinjar are still in ruins months or years after IS militants were driven out. In Sinjar, from which IS withdrew in November 2015, the historic town centre has been reduced to rubble and electricity comes only from generators.

Frustrated by the slow pace of government reconstruction, some citizens have begun taking matters into their own hands, with volunteers cleaning the streets and residents rebuilding their own houses and businesses.

But both inside and outside Iraq, many are anxious that a stalled reconstruction effort will lead to growing resentment toward the Iraqi state and plant the seeds of extremism again.

Representatives of more than 70 countries took part in the International Conference for Reconstruction of Iraq held in Kuwait in February 2018. After three days of talks, donors pledged $30 billion in new aid. But this amount falls far short of the $88 billion the Iraqi government says it needs.

Turkey, which has an interest in strengthening the Iraqi state to head off a push for Kurdish independence, pledged $5 billion in credit, the largest amount. The US pledged $3 billion, also in credit, not direct investments. Saudi Arabia, which wants to strengthen its relationship with the Shia-majority country as part of its regional competition with Iraq, pledged $1.5 billion. Kuwait pledged $1 billion in loans and $1 billion in investments, while the United Arab Emirates only pledged $500 million in aid but said it had $5.5 billion in private sector investment in the country. Iran later announced that it, too, would open a $3 billion line of credit for rebuilding efforts.

The funding shortfall may reflect the fact that donors feel overstretched, particularly because of the ongoing war in Syria, as well as a lack of trust in Iraqi institutions to carry out the rebuilding projects as planned.

Transparency International ranks Iraq 169 out of 180 countries in its corruption index, meaning it has one of the highest perceived levels of corruption in the world. Corruption, inefficiency and nepotism hampered earlier reconstruction efforts after the 2003 US invasion of Iraq and subsequent outbreak of civil war, with many projects running years behind schedule and tens of millions of dollars over budget.

“If communities in Iraq and Syria cannot return to normal life, we risk the return of conditions that allowed IS to take and control vast territory,” US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said at the donor’s conference. “We must continue to clear unexploded remnants of war left behind by IS, enable hospitals to reopen, restore water and electricity services, and get boys and girls back in school.”

Also speaking at the conference, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said, “Reconstruction and development programmes must go hand in hand with a strategy to prevent the recurrence of violent extremism and terrorism in Iraq.”

The UN is appealing for $482 million for the first year of its Recovery and Resilience Programme in Iraq and another $568 million to help stabilize high-risk areas. The programme aims to complete small-scale projects quickly to “help ensure that people see tangible improvements in their daily lives at the start of the reconstruction process, rather than waiting years to benefit from large-scale infrastructure projects and structural reforms”.

Analysts also pointed out the dangers of a stalled reconstruction effort. ‘We should keep in mind that extremist groups like IS emerged from the failure of the government in providing basic services to its people and from the failure to maintain an attachment between the state and parts of society,’ wrote Mesut Ozcan, a senior associate fellow with the Istanbul-based think tank The Sharq Forum.

Some have accused Baghdad of having sectarian motives for moving slowly on the reconstruction of former IS-held areas, which are primarily Sunni, while the central government is largely Shia.

“We haven’t received a single dollar in reconstruction money from Baghdad,” Ahmed Shaker, a council member in Ramadi told CBS News. “When we asked the government for money to rebuild, they said: ‘Help yourself, go ask your friends in the Gulf,’” referring to the primarily Sunni demographics of the Gulf countries.

Ozcan added that a worsening of sectarian tensions and a perception that the central government is passing over the Sunni-dominated areas could lead to another round of conflict. ‘Currently, there is a widespread understanding among Iraqi politicians to avoid a sectarian agenda,’ he wrote.

‘But if the future governments of Iraq fail to create a comprehensive plan for the reconstruction of the cities and fails to address the expectations of its citizens with different ethnic and sectarian backgrounds, then there will be similar problems in the future.”