Dana Hourany

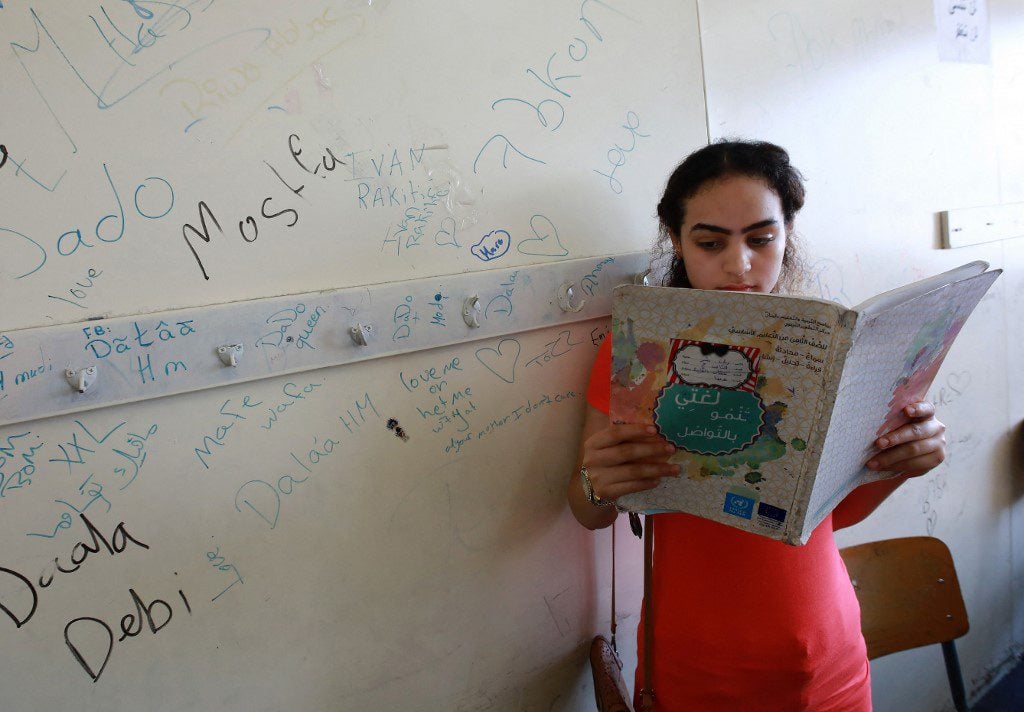

In 2021, one in five Palestinian refugees—including Ghada Daher’s daughter—failed the state-official exams.

Daher, a Palestinian activist in Beirut’s Mar Elias Palestinian refugee camp and an UNRWA school graduate, fears that her daughter is not receiving the same level of education that she once did.

“With the addition of difficulties like packed classrooms, disorganized timetables, and absent instructors, everything has changed. UNRWA schools’ educational programs are in jeopardy,” Daher told Fanack.

In Lebanon, 65 free schools are run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). Fanack was informed by an agency official that donors needed to prioritize the recent outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine and the ongoing crisis in Syria. This, along with Lebanon’s economic meltdown, has had a substantial impact on the organization and its operations. Consequently, the organization has been struggling with a persistent shortage in funds, which has forced a severe scaling back of services.

UNRWA is primarily responsible for providing aid to Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and the West Bank. There are presently more than 479,000 refugees living in Lebanon alone, while actual numbers may be higher. Contrary to popular belief, the organization only offers basic healthcare, infrastructural, financial, and educational services; it neither manages nor oversees refugee camps.

As activists and experts warn of potential escalations that threaten the camps’ internal safety – either by organized protests or hazardous migration routes – the sense of alienation is growing by the day for Palestinian refugees who are wedged in a country experiencing its worst crisis in many years and are forbidden from returning home.

The reality of being Palestinian in Lebanon

Lebanon’s economic crisis is one of the worst financial crises the world has experienced in the past 150 years, according to the World Bank.

More than 90 percent of the value of the Lebanese lira has been lost, unemployment rates have skyrocketed, and around three out of every four of the country’s 6.7 million are now living in poverty. Every inhabitant, whether local or foreign, has been impacted, but not equally. The Lebanese government imposes draconian work restrictions on the most vulnerable populations, such as the Palestinian and Syrian refugees, severely impacting their ability to support themselves and their future.

Palestinians are barred from over 30 professions including engineering, law and medicine among others and are largely limited to the informal economy.

Hairdressers, cosmetics artists, car mechanics, package deliverers, and servers in restaurants are among the most in-demand informal jobs at present, according to Daher.

“Demand for these positions has flooded the market. Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese choose to access these domains, which are rarely profitable – but do bring in some income,” she said.

UNRWA found that 68 percent of the surveyed Palestinian families have been eating fewer meals per day, 62 percent have reduced the amount of food consumed, and 28 percent of the adults are eating less in the best interest of their children in its 2022 report on the livelihood of Palestinians in Lebanon, which was obtained by Fanack.

According to Huda Samra, a spokesperson for UNRWA, “nearly all Palestinian families are living below the poverty line” at a rate of 93%.

“[Private] generator fees have spiked exponentially, so families have ditched electricity. Others do not buy gas canisters anymore so they rely on uncooked basics like bread and thyme. This has unfortunately worsened the health conditions [of residents] inside camps,” Samra said.

In Lebanon, 1,275 Palestinian students dropped out of school during the previous academic year. UNRWA noted in its report that among many other factors, psychological anguish was mentioned as the primary cause by 55% of those students.

“The situation is becoming unbearable for us,” Daher said. “We fear the agency might completely shut down and abandon us. They are our only lifeline; we have no one else to turn to. It’s their responsibility to procure the necessary funds to help us,” Daher said.

Students as the latest victims

Daher’s 15-year-old daughter, who had to repeat 9th grade, reports to her mother bouts of depression, anxiety, and loss of drive to pursue her studies since the beginning of the school year in September.

“Some classes have over 50 students. How can teachers and students focus under such conditions? Some schools don’t even have electricity and running water,” Daher said.

She claims that schools have failed to provide curriculums and that students receive their class schedules on a day-to-day basis.

“Students have lost all motivation to remain in school and disregard any prospect of a career in this country. They even tell us ‘why study when I, as a Palestinian cannot even get a job?” the activist added.

The Palestinian teachers’ union and other activist groups in refugee camps have launched a series of protests in front of UNRWA offices, demanding instant action from the agency.

According to Samra, UNRWA has already hired more instructors and is presently conducting a student census to determine the total number of teachers needed to reduce overcrowded classrooms by half.

“The agency follows a clear plan of action; we wait until the school year has launched before we carry a student count in the first two weeks to ensure we have the correct number of teachers and available classrooms,” the spokesperson said.

“We can’t, however, appoint more teachers than needed,” she continued.” This is why we have to wait. Sometimes the number of registered students differs from the reality on the ground.”

Al Waleed Yahya, editor at the Palestinian Refugee Portal, claims that many parents made the decision to remove their kids from Lebanese public and private schools, leading to a surge of students into UNRWA’s already overcrowded classrooms.

“There is an increasing need for additional schools to be built in refugee camps, and parents are finding it difficult to pay for transportation costs. Therefore, as the crisis intensifies, the demands are increasing,” Yahya told Fanack.

In spite of the UNRWA’s efforts to ease some financial strains by providing stationery, he continues, many families were forced to provide school supplies for their children without any support.

“With the little resources we have, we’re doing the best we can. Although we maintain that service standards fall short of our aspirations, the effects of the conflict in Ukraine, the food crises in Sudan, Yemen, and Libya, as well as the Syrian refugee crisis and floods in Pakistan, have diverted attention from Palestinian refugees globally,” Samra said.

Yahya and Daher both agree that the COVID-19 pandemic was a contributing factor in the education problem and UNRWA’s shortcomings. The activist and editor said that children with one mobile phone for every family and no access to tablets, laptops, or even mobile data and wireless internet were expected to attend classes, prepare for, and pass online examinations under the most difficult circumstances.

Is the worst yet to come?

UNRWA is currently looking to partner with UNICEF to fund an initiative to alleviate the transportation burdens, Samra notes.

Meanwhile, small-scale initiatives such as “A Uniform For You” campaign and other Palestinian diaspora-funded efforts have taken it upon themselves to dispense stationeries and school uniforms.

However, Yahya maintains that temporary fixes for long-term problems are not sustainable.

“UNRWA is the only source of stability for Palestinian refugees. Their work protects camps from collective outbursts of rage and potential security threats,” Yahya said.

The Lebanese crisis have driven cases of violence to soar and has put vulnerable social factions at risk of erupting from despair, Yahya added.

Activists are warning of escalation toward UNRWA, or mass demonstrations that threaten the camps’ internal safety if solutions are not presented immediately.

“Hunger drives people towards the worst. What do you expect this neglected generation to do? It seems like there are only two options; to die at sea or commit suicide,” Yahya said.

This summer, sea migration from the Middle East to Europe reached alarming levels, turning nations like Lebanon into a launchpad for desperate migrants, including Palestinians, Syrians, and its own citizens who are risking death in the Mediterranean Sea for a better chance at life in Europe.

“This is a form of revolt in my opinion. It’s like the Palestinians are crying out ‘either you notice us or we kill ourselves.’ Some even entertain the idea of marching toward Palestine and risking death at the hand of Israeli soldiers,” the editor said.

Israel has not allowed the right of return for Palestinians who were forcibly uprooted from their homes in 1948. As their host nation, Lebanon, becomes more hostile to all of its citizens, the ambiguity has thus kept the refugees in a perpetual state of limbo and intense grief.

“I tell my daughter that being Palestinian means resisting, in an effort to inspire her. We oppose wars, assaults, and economic conflicts,” declared Daher. “I try to reassure her that there’s a chance we’ll go back to our country someday. But for now, we must continue to remain resolute.”