Demonstrations to protest the rising cost of living have subsided in the Sudanese capital Khartoum and some other cities in Sudan. The demonstrations did not pose a serious threat to the regime, but they sent a clear message that the Sudanese people’s patience with the economic crisis has ended.

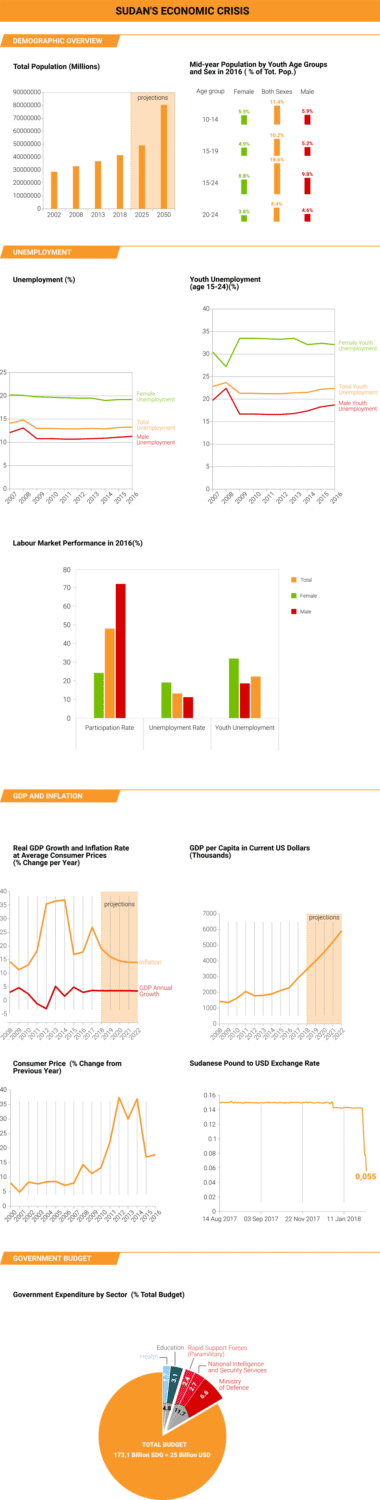

The demonstrations broke out in late January 2018, following the government’s announcement of the new budget in December 2017. This included the scrapping of basic food subsidies, which saw the price of bread rise by 100% overnight (from half a Sudanese pound to one pound or $0.033). The government also devalued the currency to 31.5 pounds to the dollar in February, after raising it from 6.6 pounds to 18 pounds to the dollar in January. The official inflation rate is 34 per cent annually, but many believe the actual figure is much higher. The figures available put unemployment at around 15 per cent.

The budget for 2018 amounts to about 173.1 billion pounds ($25 billion, according to the official exchange rate of 6.9 pounds to the dollar at the time).

About two thirds of that has been allocated to security, defence and presidential expenses, with only 13.9 per cent for education and public health.

The wave of demonstrations began in central Khartoum on Tuesday 16 January 2018, following calls by the Communist Party, which is small but influential among professionals and university students. The police met the demonstration, which was attended by approximately 1,000 protesters, with tear gas and batons. The protestors were dispersed before they reached the presidential palace and dozens were arrested.

Although some criticized the Communist Party’s unilateral call for the demonstration without consulting other parties and opposition groups, most political parties issued statements supporting the move. It also seems that the demonstration has succeeded in achieving its political objectives despite the relatively small number of participants. It received wide media coverage inside and outside Sudan, highlighted the dire economic conditions, broke the barrier of fear, especially after the bloody crackdown against similar protests in September 2013 in which dozens of people were killed.

Moreover, the demonstration presented the Communist Party as an advocate for the poor after it had been weakened by internal divisions and the harsh treatment to which it has been subjected since the Islamists took power in 1989.

The Ummah Party took advantage of the initiative, calling for a subsequent protest rally outside the Omdurman School on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Khartoum. Leaders of all the opposition parties also supported the rally as show of unity of the opposition. However, riot police intervened early, attacking the protesters with tear gas and batons and arresting dozens of women, including Sara Necdallah, the wife of Ummah Party head Sadiq al-Mahdi, three of his daughters and his son al-Siddiq. They were later released although a number of party leaders remained in detention.

The police dispersed subsequent rallies and protests in Omdurman and some districts of Khartoum and other cities such as Wad Madan in central Sudan, Port Sudan in the east and Nyala in the west, even as opposition parties called for continued demonstrations in residential neighbourhoods.

By suppressing the demonstrations, the government has restricted freedom of expression, which is a right enshrined in international law and the country’s constitution. Sudanese researcher Dr al-Nour Hamad believes that the government’s intransigence has ended in two failures.

In an article published online, he said: “The government did not allow the protest march, which disproves claims that it came to power through free elections and that it does not object to peaceful demonstrations.” International media outlets circulated pictures and videos recorded by activists during the demonstrations.

Social media websites also played an important role in mobilizing demonstrators. It could even be argued that social media activities have had a greater impact on the Sudanese authorities than the demonstrations themselves. A week later, President Omar al Bashir announced that he will devote more resources to the ‘‘Electronic Jihad’, a shady hacker group that spearheads the government’s efforts at cyber warfare.

The riot police intervened vigorously to prevent the demonstrations and disperse the protesters, but the intervention was relatively restrained compared with the heavy-handed approach taken in September 2013 that killed dozens. Live ammunition was not used, and only a limited number of people were wounded.

The security forces also took preemptive action. These included occupying Martyrs’ Park in Khartoum, where one demonstration was supposed to begin, and closing the side streets leading to the park. They also carried out a wave of arrests ahead of the announced demonstration.

The arrest campaign focused on journalists and political activists, in a bid to limit the spread of news about the demonstrations and coverage by neutral and professional press and media organizations, including Reuters and Agence France Presse. Moreover, a written circular distributed to Sudanese newspapers banned them from reporting on the demonstrations. Most journalists were released one or two days after the demonstrations ended, with the exception of a few Sudanese reporters who remained in detention for a longer period of time, including journalist and activist Amal Habani, who won the Amnesty International Media Award and had been arrested several times before.

Pro-government activists on social media, likely to be members of the government-funded online defence force or ‘Electronic Chicken’ as the Sudanese like to call them, followed a plan to intimidate citizens and dissuade them from participating in the demonstrations. They repeatedly warned that any action against the government would lead to chaos and lawlessness, as has happened in Libya, Syria and Yemen. The warnings were clearly designed to tap into deep fears in a country that has been ravaged by decades of civil war.

In addition to its online ‘army’, the government mobilized another tried and tested weapon: a fake external enemy. Amid its decisions to eliminate subsidies and in light of the demonstrations, Khartoum announced Egyptian and Eritrean military amassing in the neighbouring Eritrean region of Sawa with the aim of targeting Sudan. A state of emergency was declared in the border state of Kassala and military reinforcements consisting of rapid response forces were sent to the area. However, the talk about the military amassing evaporated once the demonstrations subsided.

Once again, it seems that the Sudanese opposition has been unable to exploit widespread popular resentment against the government because they are weaker and more divided than the government. In addition, peaceful means of opposition such as demonstrations and strikes can no longer mobilize large numbers of citizens in cities, the demographics of which have changed due to the migration of millions of impoverished people from rural areas in the last two decades. These rural migrants have no idea about staging demonstrations and strikes. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of educated urban residents who are capable of organizing protests have migrated to Gulf and Western countries.

Despite this, the economic and political challenges facing the country are too big to be remedied through purely financial means like the ones recently taken by the government.