Introduction

Political instability prevailed in Sudan throughout the sixty years of national independence that began in 1956. The country has witnessed three military coups that set up authoritarian regimes that ruled for 48 years. The democratic periods lasted for a total of only fifteen years. Another feature of Sudan’s instability is the civil wars that have continued since independence, except for eleven years of peace, from 1972 to 1983. Sudanese political crises have manifested themselves in coups, wars, economic decline, administrative chaos, and corruption.

Instability may be explained by the lack of the ability to reach consensus, to find a compromise. The elites who have long been in power offered nothing to address the country’s crisis except a recourse to the military coup as a remedy to political disagreements or military solutions to remedy the demands of marginalized areas, such as the south and Darfur.

There was likewise no solution for the aggravated economic inequality and uneven development. In the face of organized opposition that sought to restore and consolidate democracy, peace, equality, and the rights of citizens, these ruling elites, in addition to resorting to repression, mouthed the slogans of political Islam – in contrast to democracy – as the only solution to the problems that faced the country.

The first civil war between the north and south ended in 1972, but another broke out in 1983. The wars had profound effects on the lives of the people; they suffered famine, and more than four million people were displaced. According to some estimates, over the course of two decades, more than two million were killed or died indirectly because of the war.

Peace talks began in 2002 between the Sudan government and the rebel movement of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and ended successfully with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in January 2005. A period of autonomy culminated in a referendum that resulted in the south’s separation from the north to form an independent country.

Another war broke out in Darfur in 2003, displacing nearly a million people and causing hundreds of casualties. Until at least June 2016, the United Nations, in cooperation with the African Union, still has a large peacekeeping operation in Darfur; UNAMID, established on 31 December 2007, struggles to stabilize the situation.

Under various governments, there has been constant, intense political conflict over the constitution. The federal system dominated the debate before and after independence, as it demanded Southerners for their region. Even though the military government of the 1958 regime suppressed freedoms, discussions on constitutional issues continued. The October 1964 revolution reopened the door for that discussion after the restoration of democracy.

The post-1964 discussion focused on what sort of constitution the country should adopt, Islamic or secular? The constitution committees of the first and second constituent assemblies dealt intensively with that issue.

The right-wing parties traditionally adhere to the Islamic constitution option, in opposition to the secular camp, which has been associated with modern forces and urban elites and a better-educated population led by leftist intellectuals. The decision to dissolve the Communist Party and expel its deputies from parliament in November 1965 can be understood as an expression of the Islamists’ growing power.

They aimed to diminish the influence of the Communist Party and other modernist forces that emerged strongly after the October 1964 revolt, backed by professionals and educated people who had gained representation through graduate constituencies – created in response to demand for more representation for people with secondary education.

The parliament decided to abolish these special constituencies in 1968. The advocates for an Islamic constitution were also those who had rejected a federal system for the south, which had been promised at the declaration of independence. They belonged to the political parties who preferred a centralized rather than a decentralized system and a presidential system with extensive powers for the president and limited powers for a prime minister, rather than a parliamentary system.

On 25 May 1969, Colonel Gaafar Numeri led a coup against the supporters of an Islamic constitution. The country entered a new era, and the regime issued its own secular constitution, which restricted freedoms and political action under a one-party system. In 1983, however, Numeri turned his back on secularism, announcing “the application of Islamic Sharia laws” and began to impose harsh Islamic penalties. These laws threatened national unity; civil war broke out again in the south in 1983.

Numeri was overthrown in April 1985 by a popular uprising supported by the army. The democratically elected government of Sadiq al-Mahdi endeavored to reach a peace agreement with the rebels in the south. Still, those efforts were halted by the Islamist military coup in June 1989. Since then, Omer al-Bashir has ruled the country in coalition with various Islamist groups.

The Executive

Executive power consists, at the national level, of the president and the Council of Ministers. On the state level, the executive branch consists of governors and state councils of ministers and other appointed officials at the national and state levels.

The executive power in a presidential system is vested in the president; the Council of Ministers assists the president in executive matters but does not share power with the president. The present amended Interim Constitution of 2015 makes Sudan a federal presidential state. Nine constitutions had governed Sudan since the independence in 1956. The protracted political instability had made it difficult for the various political parties and ethnic groups to agree on a permanent constitution.

The present (interim) constitution gives the president broad powers. Article 58 states that the president is the head of state and the head of the government and represents the people’s will and the power of the state.

The president safeguards and protects the country’s security and safety, supervises the constitutional institutions, guides foreign policy, represents the state in foreign relations, appoints ambassadors, endorses the credentials of foreign ambassadors, ratifies international treaties and agreements (with the consent of the national legislative body), appoints persons to be constitutional and judicial offices, heads the sessions of the Council of Ministers, calls, postpones, or ends national legislative sessions, declares war following the provisions of the constitution and the law, declares and ends states of emergency following the provisions of the constitution and the law, initiates constitutional amendments and legislation, approves laws, ratifies death sentences, grants amnesty, and remits convictions and commutes sentences by the provisions of the constitution and the law. The vice president shares with the president the responsibility for declaring war and the proclamation of the end of states of emergency.

The president appoints, among other officials, the vice president, the Council of Ministers, state ministers, judges of the Constitutional Court (with the consent of two-thirds of the Council of States members), the chief justice, who is the president of the Supreme Court.

The approval of the president is required before draft laws come into force. The president has the right to veto bills, but the national legislature can override this veto with a two-thirds majority of both chambers. The national legislature is empowered to impeach the president or vice president by a three-quarters majority of both chambers. Anyone can challenge any action by the president or the Council of Ministers before the Constitutional Court or any other court.

The Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir abolished the prime minister’s position after the military coup that brought him to power in 1989. He finally reinstated the position in March 2017, appointing Vice-President Bakri Hassan Saleh. The appointing of a prime minister and the delegation of some of the president’s powers are in line with reforms proposed by a year-long national dialogue between the government and several opposition groups. However, few observers believe the decision will loosen al-Bashir’s grip on power.

The Council of Ministers’ decisions prevail over any other executive body; a simple majority takes decisions; all ministers and other officials are jointly and collectively responsible for the Council’s decisions. The Council of Ministers’ powers includes planning state policies and the initiation of national bills and the national budget, international treaties, and other bilateral and multilateral agreements. The Council receives reports on the national ministerial performance to review and take action and the regional executive performance of states for informational or logistical purposes.

On the state level, the executive branch consists of the governor appointed by the president, according to the amendments to the Constitution passed in January 2015, and not directly elected, as before. The governor appoints the Council of Ministers of State. The state Legislative Council has no power to depose the governor; the president holds this power. Before the amendments, the state legislature could remove the governor by a vote of no confidence with the consent of three-quarters of its members after the governor spent at least twelve months in office. A state minister can be removed by a two-thirds majority of members of the State Council of Ministers.

The amendments to the constitution in 2015 bestowed on the president the power to appoint governors of the states instead of their being elected. In practice, that annuls the federal system itself, which was introduced mainly to resolve disputes and eliminate regional grievances. The amendments undermine the federal government’s basis and turn it into what is simply a local government within the highly centralized state.

Although the interim constitution does not provide a political representation of specific regional or marginalized groups in the executive branch, the Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement and the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur provide the representation of regional interests. These agreements are, however, temporary arrangements negotiated with certain regions.

The Judiciary

The judicial system includes regular courts (criminal and civil), military courts, tribal courts, and special national-security courts. These courts are exempt from certain legal requirements, particularly regarding the rights of the accused. The chief justice of the Supreme Court heads the entire judiciary and is accountable directly to the president. Civil justice is administered by the Supreme Court, courts of appeal, and courts of the first instance. Criminal justice is administered before high courts, which are a part of regular courts. The Sharia division of the judiciary includes several courts headed by the Grand Qadi. The judiciary, however, remains largely subject to the executive branch; the president appoints the members of the Supreme Court.

Legal System

The Sudanese legal system is a mixed system that includes Islamic law and the traditions of the British common law. The many years under British colonial rule left the country under the British legal system’s influence because of the weight given to British legal precedent and most lawyers and judges having been trained in Britain. In 1970, an attempt was made to revise the legal system, and a new civil law was drafted, which copied, in large part, the Egyptian Civil Code of 1949.

This significant change in the Sudanese legal system was controversial because it ignored existing laws and customs and used many terms and legal concepts borrowed from Egyptian law. This caused serious problems in legal education and training. In 1973 the government abolished this law and returned to the legal system that prevailed before 1970.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s demand that the country’s laws be based on Islam led to the formation of a special committee during the rule of Numeri that was charged with reviewing laws to make them consistent with the Sharia. This was the origin of the “September Laws,” essentially Islamic law, which was still in effect when the Muslim Brotherhood party held power in 1989.

Sharia Law

Following national reconciliation in 1977, Dr. Hassan al-Turabi, the secretary-general of the Muslim Brotherhood, assumed chairmanship of a committee entrusted with reviewing secular laws to make them consistent with Sharia. The committee drafted seven bills, including the Zakat Fund Bill (zakat; obligatory alms-giving/tax) and the Sources of Judicial Decisions Bill, but the only bill that became law was the Liquor Prohibition Bill. The committee also called for the application of Hudud (Islamic punishments, including amputation and death) and prohibited interest on loans.

During the following six years, no Islamic laws were issued, except the Zakat Fund Bill. But after the appointment of Dr. al-Turabi as attorney general in November 1981, Islamization proceeded and reached its peak in September 1983, when President Numeri issued the proposed Islamic laws by a republican decree. These September Laws made Sharia the country’s law after the People’s Assembly passed the laws, in November 1983, without discussion, including the Sources of Judicial Decisions Law and a new criminal law that included Hudud provisions.

The application of Hudud aroused resentment among secular Muslims as well as non-Muslims. There was concern about the imposition of religious laws on a multi-religious society and concern for the Islamic religion’s reputation. The Hudud application raised strong opposition to the Nimeiri regime, and several judges refused to apply the new provisions. They were discharged, and others, who were ineligible for work in the judiciary, were appointed to continue the Hudud application. This contributed to a reign of terror in the courts. At the same time, many moderate Muslims were excluded from discussing the issue of Islamic law.

In 1985, there was a growing rejection of these laws, and belief in these laws’ injustice continued to grow. Following the overthrow of Nimeiri in 1985, the application of the harsh Islamic penalties was halted. Still, neither the military government that then took power nor the democratically elected Umma party government that followed could abolish Sharia laws. However, that was a key demand of the opposition and the armed movement in the south.

When Sadiq al-Mahdi’s government took steps to respond to these demands, Dr. al-Turabi’s party, fearing this new development, launched a coup and took power just before the government began its session to vote on repealing the September Laws. Stoning, flogging, crucifixion, and amputation remain legal punishments in Sudan. After the Naivasha agreement with the SPLM in 2005, Islamic laws no longer applied to the south. Since the secession of South Sudan, while it remained applied in the North.

Local Government

During Egyptian-British condominium rule, Sudan was divided into eight provinces under the authority of the governor-general. From 1937 to 1942, native administrations were established to provide social services in their areas.

In 1943, provincial councils were formed to oversee activities outside the scope of local administration. City councils and municipalities were set up based on the pattern of the British councils. In 1951, the Local Government Act was passed in a serious attempt to adapt the British local government’s principles to the circumstances of a developing country such as Sudan. It relied on the traditional native-administration system consisting of local tribal sheikhs and other dignitaries. Under this system, local tribal leaders enjoyed limited judicial power. District councils were established in 1960. After the 1964 October Revolution, the native-administration system was abolished in some areas. Sudan has now divided administratively into eighteen states, divided into 133 localities.

Political Parties

The establishment of Sudanese political parties was linked to the Graduates’ General Congress’s differences, the first all-inclusive national organization established in 1918. In the mid-1940s, Congress ceased to exist, and political parties emerged. Despite the liberal origin of these parties, to enhance their popularity, some sought to link themselves to religious sects, which were a prominent feature of these parties. The so-called ‘Independence’ political orientation was sponsored by Imam Abdel-Rahman al-Mahdi, the Ansar sect leader. The other religious sect, Khatmiyya, led by Ali al-Mirghani, supported unification with Egypt.

By the early 1950s, there were two clear political blocs in Sudan, the Unionist and the Independence. The independence parties called for complete independence from both colonial states (Britain and Egypt). They include the Umma Party, founded in 1938, which relied initially on its slogan “Sudan for the Sudanese” rather than adopting a specific party program. The Nationalists’ Party, founded in 1944, called for self-determination and a specified transitional period before gaining independence from the condominium.

The Republican Party, founded in 1945 by Mahmoud Mohamed Taha, was the first pro-independence party, which published a program in which the two religious sects (Ansar and Khatmiyya) were criticized for collaborating with Britain and Egypt. The party’s program was based on Islam. The Socialist Republican Party, founded in 1951 by some of the leaders of the native administration (tribal sheikhs), called for the independence of Sudan and full, immediate self-rule. Today, only the Umma party (with its many factions) remains popular and one of the country’s largest political parties.

The unionist parties were several parties organizationally different but with a common political vision, which called for a union with Egypt. The Ashiga (Brothers) Party, founded in 1943, won the support in 1944 of Sayid Ali Mirghani, leader of the Khatmiyya sect. The Federal Party, founded in September 1944, called for a union similar to the Commonwealth; the party’s principles provided for a democratic system of government based on social justice and national unity. The unity of the Nile Valley Party, founded in 1945 after a dispute with the leaders of the

Ashiga Party was the most radical, calling, as it did, for unity between Sudan and Egypt. The Liberal Party, known since 1944 as the Liberal Unionists party, called for the establishment of a free Sudanese government in confederation with Egypt. The party split into two wings called for full independence and merged later with the Umma Party. The other wing kept the name of the Liberal Unionists and adhered to its principles.

The National Front Party, founded in 1951, called for unity represented by one head of state. The National Unionist Party was founded in Cairo in November 1952, when the unionist parties were invited by Mohammed Naguib, the former Egyptian president, to discuss Sudan’s constitutional developments. The unionist leaders announced the dissolution of their parties and the establishment of the National Unionist Party (NUP), presided over by Sayyid Ismail al-Azhari, who later became the first Sudanese prime minister. The NUP also split: the Khatimiya sect separated into the People’s Democratic Party for some time but reunited with the NUP in 1967 under the name Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Today the DUP has broken into many factions, despite efforts to reunite the party.

Present-day Sudanese political parties, particularly those that participated in governments, can be classified into three main groups. First, the Umma and the Democratic Unionist parties represented the religious sectarian parties (with all factions and mergers). Second, ideologically radical parties, such as the Sudanese Communist Party, the National Islamic Front (National Congress and the People’s Congress), and the Arab Baath. Third, the regional parties including the Liberal party (from the south), the Sudan African National Union, and the Sudanese National Party (from the Nuba Mountains).

More than 70 political parties participated in the National Dialogue Conference held in Khartoum in October 2015. More than ten others boycotted the dialogue conference. Many factors cause divisions among both the old established parties and the newly founded parties. For example, the Umma Party, the Democratic Unionists, the Communists, and the Baathists all split into several factions. Even the armed movements in Darfur and the East split.

Islamists

Classification into Islamists and secularists must take into account the special circumstances of the country. The vast majority of registered parties, which are constantly changing, the state in their political programs adherence to the Sharia. For example, the Muslim Brotherhood Party calls for the “realization of the Sharia of God in various aspects of life.” The Umma Party calls for “stabilization of the principles of Islamic Sharia as doctrine and lifestyle.” The Democratic Unionist program calls for “adherence to Islamic Sharia and values of the other religions.” The National Islamic Front calls for “the realization of God’s Sharia and the Islamic religion’s ideals.” This refers to the “maqadis al-shariah,” meaning five foundational goals focused on preserving faith, life, lineage, intellect, and property/wealth.

Islamists in Sudan are divided between two trends; a moderate one represented by the traditional parties based on religious sects and a radical one represented by the Muslim Brotherhood, with its various groupings. The extremists currently hold power.

The Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan was formed in April 1949 and has changed its name several times. In 1968 it was called the Islamic Charter Front, an Islamic alliance between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists (aspiring to live as did the early Muslims). Dr. Hassan al-Turabi chaired the Brotherhood in 1969 when some members broke away to form, in 1979, the nucleus of the current party led by Sheikh Sadiq Abdalla and Dr. al-Hiber Yousif.

Again the name was changed to the National Islamic Front (NIF). During the short-lived democracy of 1986-89, Dr. al-Turabi was its secretary-general. The NIF organized the 1989 coup against the democratic regime and established a new political organization called the National Congress, which is now Sudan’s ruling party. When the party split in a conflict between al-Turabi and President Bashir, Dr. al-Turabi founded his own group, the Popular Congress Party, in 1999. On March 5, 2016, Dr. Hassan al-Turabi passed away in a Khartoum hospital after having suffered a stroke.

Opposition parties allied against the Islamic militant regime are more or less secular. They express their goal as a “civil state.” The leftists, the regional parties, and some factions of the traditional parties comprise this trend.

Leftists

The Sudanese Communist Party was formed in 1946 as the Sudanese Movement of National Liberation. Other leftist trends include parties influenced by the Arab National socialism, such as the Baath party, which split into the Sudanese Baath Party, the Arab Socialist Baath Party –Country of Sudan (the Iraqi Baath Party regional branch in Sudan), and the Arab Socialist Baath Party – Organization of Sudan (the Syrian Baath Party regional branch in Sudan). The Nasserist Party (founded 1980) and the Sudanese Socialist Democratic Party (founded in 2002), and the Liberal Democratic Party 9founded 2003) also appeared on the scene.

The Military

The military has long dominated Sudanese politics. In a landmark deal signed in August 2019, following months of pro-democracy protests, the ruling military council and civilian opposition alliance agreed to share power, paving the way for elections and civilian rule.

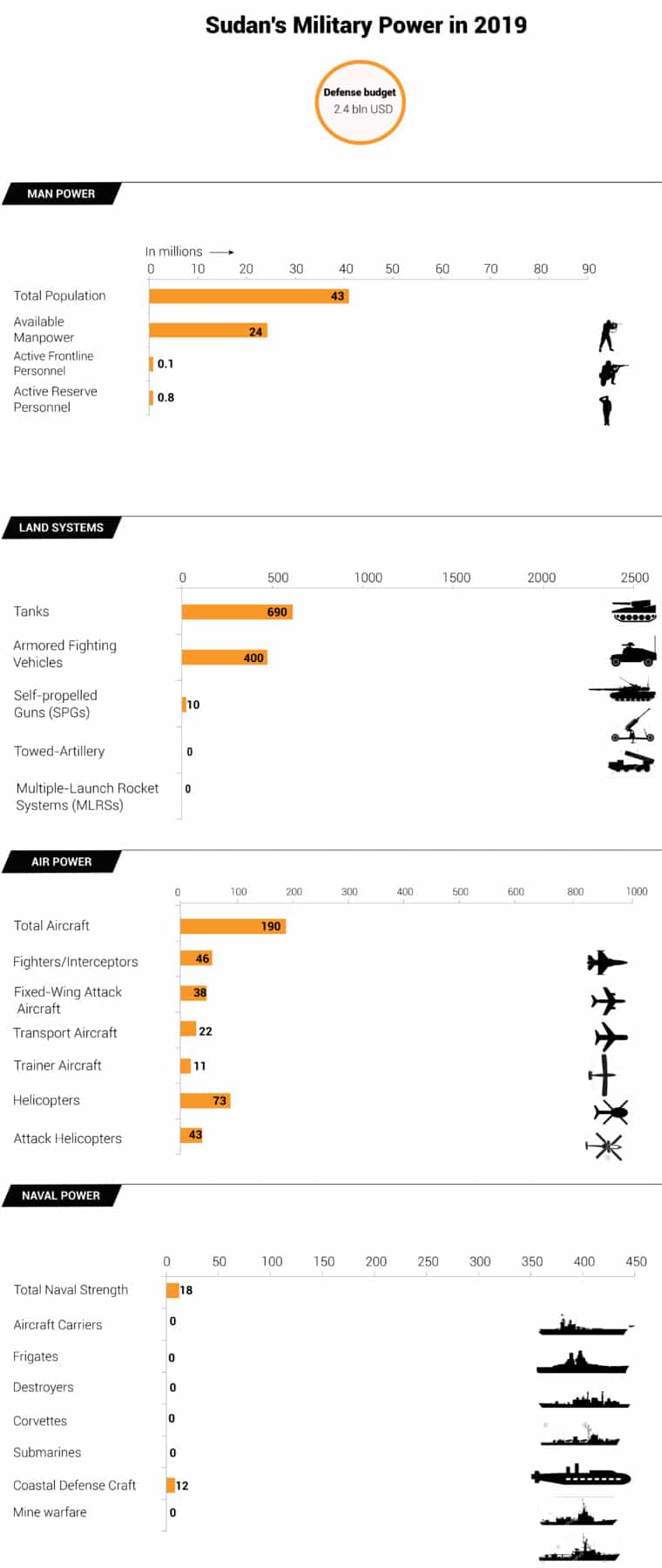

In 2019, Sudan ranked 69 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 1.2 million personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $2.5 billion. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2018, military expenditure accounted for 2.3 percent of GDP, compared with 3.9 percent in 2019 and 3 percent in 2016.

The Sudan Defence Force was established in 1925 to protect Sudan’s borders under the British. After independence in 1955, it became the Sudanese army.

The army was heavily involved in the civil wars that ravaged the country from 1955-1972 and again from 1983 to 2005. Fighting also broke out in the western Darfur region in 2003 when rebel groups began attacking government targets, accusing Khartoum of oppressing Darfur’s non-Arab population.

The Sudanese Armed Forces branches are land forces (200,000 troops), navy, and air force. Military service is compulsory for men 18-30 years of age and lasts for two years. Sudan’s military expenditures are estimated at 4.7% of GDP and more than 20% of the government budget.

Several other paramilitary groups fight alongside the Sudanese army, under its command, and with its support. The Popular Defense Forces (PDF) is a paramilitary group established in 1989 to assist the army in the war in South Sudan and defend the regime. The PDF, which is ideologically more loyal to the government than the army, has about 10,000 active fighters and 50,000 reserves. The paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, officially established in June 2013, is operated by the Sudanese Army to fight rebel movements in Darfur and the Nuba Mountains.

The roots of the RSF can be traced back to the Janjaweed militias used by the Sudanese government in Darfur since 2003. Sudan is self-sufficient in the manufacture of light weapons, armored vehicles, and ammunition, developed with Iran’s help during the last two decades.

The main suppliers of the Sudanese army recently have been China and Iran. The armed forces, especially the air force, also have old Russian military hardware.

In September 2016, the Russian newspaper Izvestia reported a Russian-Sudanese deal to provide Khartoum with 170 T-72 tanks. In November 2016, Sudan ordered six Chinese FTC-2000 training planes.

Several high-level meetings were held between Sudanese and Saudi officials, most noteworthy between al-Bashir and King Salman in May 2015.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 189,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 104,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 85,000 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 191 | 50 |

| Fighter aircraft | 46 | 39 |

| Attack aircraft | 81 | 31 |

| Transport aircraft | 23 | 33 |

| Total helicopter strength | 73 | 48 |

| Flight trainers | 11 | 71 |

| Combat tanks | 410 | 43 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 403 | 86 |

| Rocket projectors | 20 | 57 |

| Total naval assets | 18 | - |

Sudan’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

The Sudanese Army has taken part in many missions abroad, from symbolic participation in the Egyptian-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973 to the Arab Peacekeeping Force in Lebanon in 1977. In 2015 it joined the Saudi-led coalition to fight Houthi rebels in Yemen.

The Sudanese military has a long history of direct involvement in politics. It took power for the first time in November 1958, led by Ibrahim Aboud, until October 1964, for the second time in May 1969, led by Jaafar Nimeiri, until 6 April 1985, and for the third time, led by General Omar al-Bashir, from 30 June 1989 to the present.

Foreign Policy

Sudan’s foreign policy during the last 25 years has been in a state of continuous tense and apprehensive relations with almost all neighbors and the international community. When it became clear that Sudanese Islamists led by Hassan al-Turabi were heavily involved in the military coup of 30 June 1989, the world turned a cold shoulder to Sudan. The new regime in Khartoum isolated itself further by supporting Kuwait’s widely condemned Iraqi invasion in 1990.

The United States, Europe, and the Arab Gulf states immediately scaled back their relations and eventually cut back badly needed economic aid to Sudan. The country emerged isolated and empty-handed from this regional crisis, which turned its neighbors against it. However, the Khartoum government’s deviant policies continued; the Sudanese capital became a haven for radical Islamists from all over the world, including Osama Bin Laden, who moved to Sudan in 1991 and stayed there until 1996.

The United States and most European and Gulf states accused the government of Sudan of supporting international terrorism and destabilizing neighboring countries. Relations with Egypt reached their lowest ebb with the attempted assassination of former president Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa in 1995. Khartoum was charged with facilitating the attack.

The human rights records of Khartoum’s government and its harsh crackdown on its opponents invited additional foreign criticism and sanctions. On 3 November 1997, the US government imposed a trade embargo on Sudan and a total freeze of the assets of the government of Sudan under Executive Order 13067.

The Sudanese government failed to capitalize on the peace deal signed with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army rebel movement in southern Sudan in 2005, ending two decades of civil war. The outbreak of civil war in Darfur in 2003 and the atrocities allegedly committed by the government of Sudan further devastated the nation’s foreign relations. In March 2009, al-Bashir became the first sitting president to be indicted for crimes against humanity, for the government’s actions in Darfur.

Meanwhile, Khartoum worked hard to compensate for its damaged relations with the west and most of its neighbors by strengthening trade and political relations with Iran, China, southeast.

Asia, and Russia, having remarkable success in that endeavor. Chinese and Malaysian companies played a vital role in producing and exporting oil from Sudan, beginning in 1998.

After 2011, with a changing political atmosphere in the region and the world and as alliances within the Middle East shift continuously, Sudan is exploring other options and mending its fences with its neighbors and the rest of the world.

Joining the Saudi-led coalition against the Houthi rebels in Yemen in 2015 is an excellent example of this new trend. The move is intended to make up for the grave mistake of siding with Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in 1990 through reconciling with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, simultaneously sacrificing its close ties with Iran.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Sudan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: