Child marriage, the act of marrying underage children, often girls, is not a new phenomenon, but takes a critical turn for the worst for victims from countries facing war and extreme poverty. In addition to the short-term damage it inflicts on the young bride or groom, child marriage is also the cause of longer-term suffering, including rape, unwanted pregnancies, lack of access to education and the continuation of poverty in the family.

The multi-organization partnership “Girls Not Brides,” a global network of organizations working to end child marriage around the world, published in 2018 the results of a study on child marriage in Syria, a country that has been devastated by war since 2011. Although 13% of Syrian women aged 20 to 25 were married before they turned 18 even before the conflict began, the study revealed that child marriage is a growing problem for Syrian girls in refugee communities in Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Turkey. In Jordan, for instance, figures show an increase over time, from 12% of registered marriages involved a girl under the age of 18 in 2011 to 18% in 2012, 25% in 2013 and 32% in early 2014. In Lebanon, 41 % of young displaced Syrian women were married before 18 and, given that many marriages are unregistered, these figures may in fact be much higher.

The study emphasizes the fact that parents, by marrying off their daughters early, are not doing so out of cruelty but rather out of fear that they will not be able to provide for and protect them, believing that marriage might protect their daughters from harm while also providing them with a level of financial stability. What often ends up happening, however, is that the young girls face numerous hardships with early marriage, including complications during pregnancy and childbirth, violence, limited educational and economic opportunities, as well as less freedom and the inability to socialize with children their own age. These consequences are likely to negatively impact an entire generation of younger Syrians who, given they will potentially be the ones to rebuild their country in the future, may be inclined to normalize a social system that allows child marriage and family violence.

“It is often difficult to gather accurate data on child marriage, even during times of peace, because of gaps in data or child marriages being concealed due to illegality,” Heather Barr, acting co-director of the Women’s Rights Division at the international organization Human Rights Watch (HRW), told Fanack. “In the context of conflict in these three countries, gathering accurate data is even more challenging. But Girls Not Brides has documented an increase in the number of child marriages among Syrian girls displaced by the conflict and there is every reason to believe that pattern also holds true for Yemen and Libya.”

Some of the research Barr was involved in at HRW revealed that conflict and insecurity, as well as other crises such as natural disasters, can heighten the risk of child marriage. “In a crisis, parents may be struggling to feed and protect their children. They may see marrying a daughter off—earlier than they would have in peace time—as a way to reduce their burden and make it more feasible to care for their remaining children,” she said. “They may mistakenly view marriage as a way to protect a daughter from risks associated with the conflict, including the risk of sexual violence. They may simply be overwhelmed and unable to cope. And in cultures where a marriage involves a financial transaction, like the payment of dowry or “bride price”, a child marriage may offer a parent stressed by the conflict a financial gain or an opportunity to avoid having to pay a dowry themselves. Many parents, faced with the terrible choices imposed by a conflict, genuinely believe that swiftly arranging a marriage for their daughter is their only or best option to try to protect her and the rest of the family.”

Children marriage does exist outside of conflict, including in developed countries like the US and UK. But child marriage occurs the most in unstable, poor countries like Niger, Chad and Bangladesh, while countries at war fall below the rate of 30%. “We know that when families experience great stress due to factors such as a conflict, child marriage can become a coping mechanism, especially in an environment where child marriage already exists,” Barr told Fanack. “This is why conflict or other crises bring a serious risk of an increase in rates of child marriage.”

According to HRW, child marriage stories are remarkably similar from one country and region to the other, with drivers such as discriminatory gender roles, including the expectation in some cultures that sons should support parents in old age while daughters “belong” to their in-laws; lack of access to education, which drives girls out of school and increases the risk of them marrying young; poverty, including food insecurity; efforts to control girls’ sexuality and lack of access to comprehensive sex education, contraception and abortion; financial incentives, driven by dowry and “bride price” practices; and social pressures.

Facing this situation, international organizations such as UNICEF have publicly called for the need to help children, notably because of “the conflicts in the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen, volatility in Libya and upsurges of violence in Palestine that are exposing children to extreme risks, including death, injury and displacement, as well as forced recruitment into armed groups and early marriage.” In Yemen specifically, Amnesty International said that “the protracted conflict has exacerbated discrimination against women and girls and left them with less protection from sexual and other violence, including forced marriage.” The New Humanitarian published several testimonies about child marriage in Yemen, including the one of Safa’a, married at 14, who said, “brides [are supposed to] celebrate on their wedding day. But I was crying when I had to leave my mother’s room, because I knew I couldn’t achieve my dreams. My future would be in my husband’s hands, not mine.”

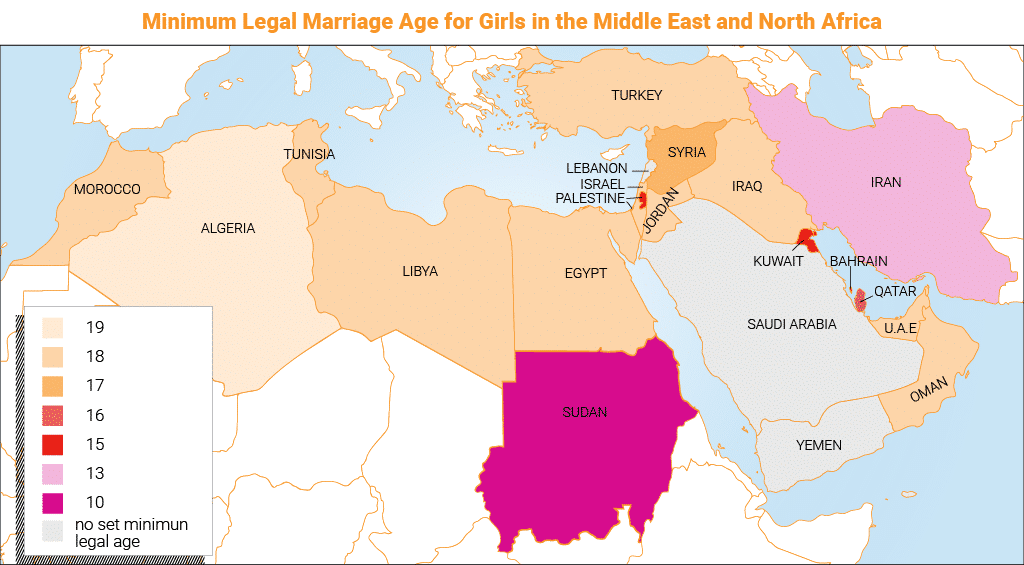

A solution to end this phenomenon cannot come quickly enough to save thousands of girls from an unfortunate fate. It is a topic that is currently being addressed through the UN Sustainable Development Goals, where countries have committed to a target of ending all child marriage by 2030. “Many organizations, including those in the Girls Not Brides network, are working on the ground, country-by-country, to urge and help governments achieve that target,” Barr said. “The response from governments has been varied. Some have taken important steps, such as reforming their laws to bring the age of marriage in line with international law (which says that the age of marriage should be 18, with no exceptions); others have developed national action plans for how to achieve the 2030 target. But some governments have been very slow to prioritize this issue or have ignored it or even pushed back against efforts at reform. In countries experiencing conflict, it can be especially difficult to compel governments to pay attention to the need to end child marriage.”

In countries overwhelmed with challenges, such as wars that spare no civilian, combating child marriage can seem to political leaders like a waste of time and energy regardless of the party they represent; especially when an entire country needs to be rebuilt and stabilized. But without equal rights for girls and women and a safer environment for children, the future will not be bright for any country that allows child marriage.