Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, the grand imam of Egypt’s al-Azhar, made headlines in early March 2019, following remarks in a televised interview regarding polygamy.

“Polygamy is an injustice to women,” he was widely cited as saying, sparking both angry and supportive reactions in the traditional and online media. Some, mostly Salafi, preachers encouraged polygamy whereas others interpreted el-Tayeb’s words as a call to reform the practice. Marrying up to four women is allowed in Islam, although this rarely happens in most majority-Muslim countries and is often socially unacceptable.

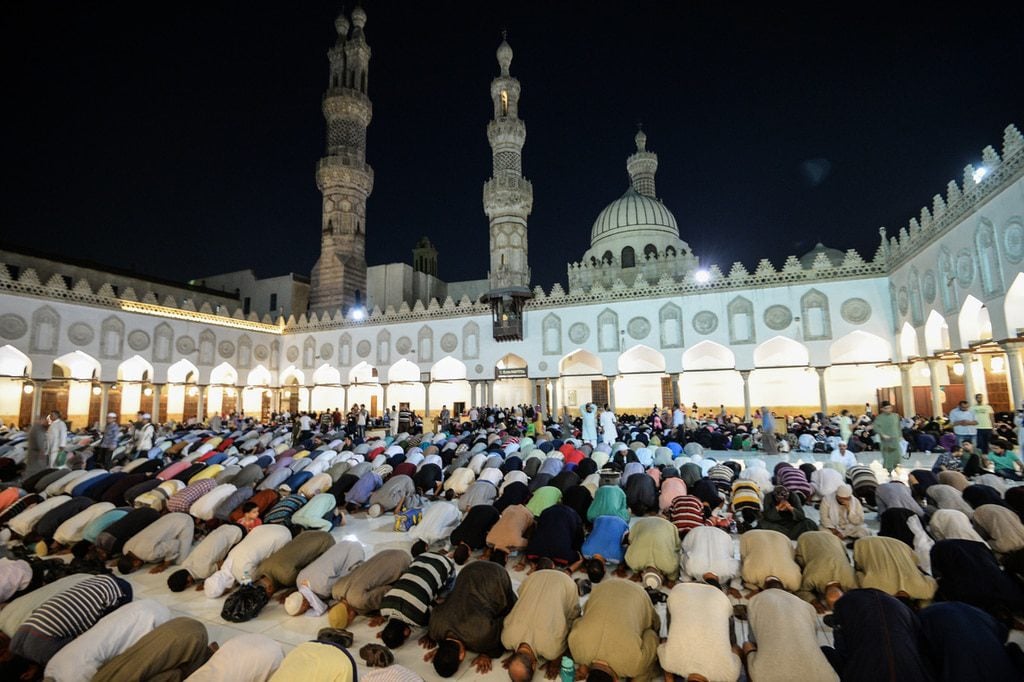

As leader of the world’s leading Sunni Islamic authority – and chosen as the most influential Muslim in 2016 and 2017 – el-Tayeb is an important religious figure. For many, and the Egyptian state in particular, al-Azhar is seen as a counterweight to the extremist thought of groups such as al-Qaeda and the self-proclaimed Islamic State. President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has frequently called for a renewal of religious discourse to counter extremism, for which he sees al-Azhar as an important vehicle.

The significance of el-Tayeb’s polygamy comments appears to have been overstated though.

“What he said wasn’t new, it is the standard position on polygamy,” researcher H.A. Hellyer, senior fellow at the US-based Atlantic Council, told Fanack.

Examining his words more closely shows that he effectively repeated and explained the verse in the Koran dealing with polygamy.

“In most cases, polygamy involves injustice to the wives and children…if there is no justice, polygamy is forbidden,” he said.

The Koran verse reads as follows:

‘… marry those that please you of [other] women, two or three or four. But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one or those your right hand possesses. That is more suitable that you may not incline [to injustice]’.

While multiple interpretations of this verse are possible, the general explanation is that polygamy is conditional on the ability to treat all wives fairly.

“The statement of the grand sheikh follows the traditional opinion on the matter, that being fair is the main condition for polygamy,” researcher Amr Ezzat of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights told Fanack.

In response to the uproar caused by el-Tayeb’s comments, al-Azhar quickly issued a statement clarifying that the grand imam had in no way called for the banning of or legal restrictions on polygamy.

Ezzat believes that certain groups exaggerated the comments in the media out of self-interest. Those pushing for a renewal of religious discourse added more weight to the comments for “propaganda reasons”, he said. The Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamists also highlighted the statements as they fit their narrative that the state is out to “destroy sharia [Islamic law]”, Ezzat said.

In August 2018, el-Tayeb made comments that some also interpreted as showing al-Azhar’s ‘moderate’ view on Islam. He said that sexual harassment was not allowed in Islam regardless of how a girl or woman dresses.

But again he did not divert from traditional Islamic teaching. “[The statement] on harassment is also a normal opinion that conforms to fiqh [Islamic jurisprudence],” Ezzat said. “However, it does respond to popular views that the woman or her clothes are responsible for harassment.”

Ezzat sees a positive development in the media discourse of el-Tayeb showing a “sensibility in dealing with women-related issues, and drawing closer to feminist discourse. But this takes place through relying on traditional fiqh to face popular perceptions and the counter-propaganda of Islamic currents.”

“For him to be so categorical about it is new, but not the substance of it, said Hellyer, adding that the statement followed the same pattern as al-Tayeb’s earlier comments on sexual harassment but is a “bit more blatant”.

Al-Azhar has historically been close to the state, and under el-Tayeb that has not changed. Throughout the volatile post-revolution years since 2011, el-Tayeb has managed to maintain al-Azhar’s key role in Egypt’s power dynamics and strengthen his own position.

Al-Sisi’s call for renewing religious discourse, however, has not been met with enthusiasm from al-Azhar. As Fanack wrote in October 2018, el-Tayeb apparently sees no need to renew Islamic discourse; it needs to be taught better in order to prevent people from using the religion to justify violence and extremism.

The relationship between the state and al-Azhar was tested recently when reports surfaced that the constitutional amendments proposed in parliament in February would include a change in the selection process of the grand imam. Instead of being chosen by al-Azhar scholars, the president would appoint the grand imam. These amendments would have been quickly abolished by members of parliament though, as local website Mada Masr reported in detail, showing that el-Tayeb is managing to maintain his strong position.

In previous cases, al-Azhar has also shown it will not divert from traditional Islamic jurisprudence. When Tunisia passed a law to permit equal inheritance between men and women, al-Azhar said this was not in accordance with sharia. Al-Azhar also denounced a mosque in Germany where women and men are allowed to pray together. The institution has refrained from denouncing Islamic State fighters as apostates, however, as only God can judge who is a Muslim and who is not.

Moreover, al-Azhar is larger than el-Tayeb alone and encompasses different perceptions and opinions within its ranks. Ezzat said that the positive remarks on women’s issues “reflect el-Tayeb’s own strategy, and not the institution or its working teams”.