Islam is the Arabic word for ’submission’, in the sense of surrendering to God’s will. It is the religion of about 1.6 billion people around the globe as of 2010, according to the Pew Research Center, which also ranks the Abrahamic, monotheistic faith as the fastest growing religion in the world.

How Islam Began

It was in the small desert town of Mecca, located in what is now Saudi Arabia and surrounded by the Byzantine and Sassanian empires, that Islam emerged in the early 7th century through revelations that Muslims believe were made to Islam’s prophet, Muhammad, by the archangel Gabriel – Jibril in Arabic.

Muhammad began receiving revelations in 610 while he was meditating in a cave on the summit of Mount Hira, outside Mecca. Muslims believe that those revelations are the words of God, conveyed by Gabriel, and that they constitute the Koran, Islam’s holy book.

Muhammad only confided in his wife and close family and friends that he had received the revelations, and it was more than two years later that he started preaching publicly.

A Religio-Social Reform Movement

According to certain historians and religious scholars, such as Vernon O. Egger, Islam emerged essentially as a ‘religio-social reform movement’, as its leader grew up an impoverished orphan who lived with his grandfather, then with an uncle after his grandfather’s death.

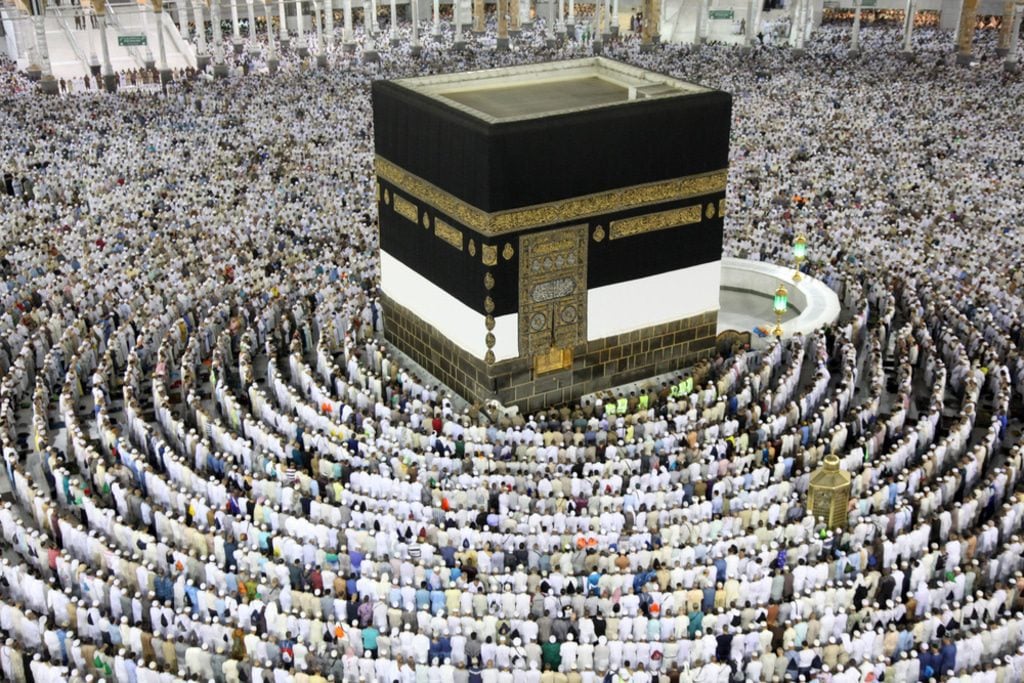

At the time, Mecca was home to the pagan Kaaba shrine and the few hundred pagan idols surrounding it, as well as a regional trade centre with unequal distribution of wealth between a rich elite and poor, underprivileged families and clans. Muhammad called on the people of Arabia “to share wealth and create a society where the weak and vulnerable were treated with respect”, according to Karen Armstrong, who emphasized Muhammad’s social message in her book on Islam’s history. It is little wonder that the early believers – with the exception of a few prominent Meccans such as Uthman ibn Affan – came mainly from among the poor, such as freed slaves and those who belonged to lesser clans and families.

The staunchest opposition to Muhammad’s message came from his own tribe, the Quraysh, which was the dominant tribe in Mecca at the time. Muhammad belonged to the Quraysh’s Banu Hashim clan, a prominent but not the most important clan in the tribe. Scholars and observers have put forward various possible explanations for such opposition. Egger and Armstrong, for example, attribute it to the nature of Muhammad’s teachings.

Egger wrote, ‘Muhammad’s teachings were … particularly galling to the aristocrats of Mecca. On the one hand, he used the traditional value of generosity against them and exposed the fact that they had betrayed those [tribal] values by becoming greedy and stingy; on the other hand, he turned upside down the traditional criterion for status, which was a prominent position in a powerful tribe. According to him, individuals with undistinguished backgrounds who submitted to God and His Prophet would fare better in eternity than the most revered tribal leader who rejected the new teaching.’

The renowned Montgomery Walt highlighted the threat Muhammad posed to the political power and influence of rich merchants: they feared that if he succeeded in attracting a mass following, he would acquire political power and possibly run Mecca’s affairs.

Their fears were eventually realized because Muhammad would indeed later control Mecca and all of Arabia. What’s more, Muslims after his death would form an empire that would stretch over thousands of miles.

Hijra: The Muslim Era Begins

Muhammad’s main protector in Mecca, his uncle Ali ibn Abi Talib, passed away in 619. Following his death, the Quraysh’s persecution (e.g. economic boycott and physical beatings) of Muhammad’s followers intensified. It was in 622 that the early Muslim community took a step that would become a turning point in Islam’s history: the hijra (migration), moving to Yathrib, which is today the Saudi Arabian city of Medina. Medina is located around 220 miles to Mecca’s north.

Islam had already started to make its way to the city by 620, after a group of its people came to Mecca and heard Muhammad preaching. Later, a full delegation representing Medina’s Arabs visited the prophet, expressed their conversion to Islam and invited him to move to their city. Vowing to obey him, they asked him to arbitrate in the city’s tribal conflicts.

The hijra marked the beginning of the ‘Muslim era’. In fact, the year of the hijra (622 in the Gregorian Christian calendar) marks the first year in the Islamic calendar, also known as the hijri calendar.

In Medina, Muhammad’s followers increased and he became recognized as the city’s political leader. He set about organizing the affairs of a new community, which comprised the immigrant Muslims (known in Islamic tradition as muhajiroon), Medina’s converts to Islam (ansar) and the Jewish tribes that were already well established in the city.

The Koranic verses that Muhammad said were revealed to him while he was in Medina focus on rulings and legislations that were relevant to his new role in running the affairs of a growing community.

Yet the city’s Jewish tribes were not always comfortable with this role. Perhaps, according to some sources, the Jewish tribes were unhappy about the new balance of power he created after mediating between the city’s tribes and clansii, who had been engaged in a long conflict prior to his arrival.

Some historians also attribute the Jews’ hostility toward Muhammad to the religious differences between them. The Jews did not accept that the new prophet was not Jewish. Muhammad, for his part, developed a more negative position toward the ‘people of the book’ (Christians and Jews who had scriptures) after the hijra.

According to many sources, members of Medina’s Jewish clans planned to kill Muhammad more than once. Muhammad expelled two Jewish clans from the city. Amid the Battle of Trench between the Muslims and the Quraysh/Mecca, and after the Jewish Banu Qurayzah clan betrayed an agreement with the Muslims and sided with the Quraysh, Muslims in Medina killed the male members of the clan and enslaved the women and children. This went down in history as a particularly controversial incident.

While in Medina, Muhammad engaged in continuous conflict with the Quraysh/Mecca, marked by a series of three battles, until his home town eventually fell to the Muslims in 630, following Meccans’ violation of the bilateral treaty of Hudaybiyah. By the time Muhammad died in 632, the Muslims controlled all of the Hijaz, the region that makes up most of the western part of modern-day Saudi Arabia.

Following his death, four of Muhammad’s early companions succeeded him in ruling the Muslim community, which would continue to expand to include Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Palestine, Iran, Afghanistan and more. These successors were given the title of caliph. During the reigns of the third and fourth caliphs, disagreements broke out among the Muslim leaders, resulting in civil war and the emergence of the Shiite Muslim sect as distinct from the Sunni sect. To this day, Shiites continue to play major religious and political roles in the Muslim world, despite being in the minority.

The Islamic Doctrine

Scholars agree on a number of key fundamentals that characterize Islam. They include, but are not limited to, the following.

Abrahamic Tradition

Muslims believe that Muhammad is God’s messenger, the last in a series of prophets God sent to complete or ‘seal’ God’s message. They believe in the prophets that preceded him, such as Abraham, Moses, David and Jesus. Most scholars agree that Islam belongs to, or is at least in general harmony with, the Judeo-Christian, Abrahamic tradition.

Muslims, however, claim that any rejection of Muhammad’s prophethood and teachings on the part of Jews and Christians is due to ‘distortions’ that accumulated in the Christian and Jewish traditions over time. The three religions have numerous key concepts in common, such as monotheism, the importance of giving charity to the poor, bodily resurrection after death, the last judgement, heaven, hell and Satan.

Tawhid: God’s Oneness

Many scholars have pinpointed tawhid as the most important concept for Muslims. Muslims are required to acknowledge God’s oneness as the only God (al-ilah in Arabic), which is why there are Arabic-speaking Christians who call God Allah as well). Allah Is the greatest, to whom all the virtuous traits are attributed in their utmost, absolute form: he is the most merciful, most generous and the most just.

Allah has no wife or offspring. He and only he may be worshipped. Islam strictly rejects all forms of polytheism and paganism. This particularly distinguished Muhammad’s message when he started preaching in Mecca because the Quraysh already believed in God, but they worshipped him through idols. Subsequently, Muslims believe that there is no religious authority (e.g. a clergy) between individuals and God.

The Koran

In a poetic language and literary style, the Koran tells stories of the past and makes vows about the future, addressing Muhammad and Muslims at times and humankind at other times. It also lays out a number of rulings on how Muslims should live their lives and organize their community, and it describes God’s traits, such as mercy, justice and power.

There is a near-consensus among Muslims that the Koran is the word of God, delivered through revelations that Muhammad received via Gabriel. Many observers have noted that almost all Muslims around the world agree on the authenticity of the Koran, despite their differences and disagreements on scores of issues, both minor and major, and despite their divisions across sects and groups.

Many historians have also agreed on the Koran’s authenticity as a historical source on Muhammad’s life, even if they find it unsatisfactory on its own and in need of supplementary sources. Montgomery Watt describes the Koran as ‘contemporary and authentic’ as a ‘primary source for the life of Muhammad’, even if it is ‘fragmentary’ and ‘difficult to interpret’.

This on the Koran’s fragmentation can be understood in the context of the book’s division into 114 surahs (chapters) that were collected and organized according to Muhammad’s instructions, which is not the same order as the chapters were reportedly revealed to him.

Another historian, F.E. Peters, wrote, ‘There is almost universal consensus that the Koran is authentic, that the text that stands before us is the product of one man.’

Obviously, secularist and non-Muslim historians who consider the Koran authentic do not see it as the word of God, as Muslims do; rather, they consider it as a credible source for what Muhammad said during his life.