Hatay has long been at the crossroads of Middle Eastern history. Nestled between Anatolia and the Levant and skirting the Mediterranean, the province in modern-day Turkey was a staging post for Alexander the Great’s campaigns and has borne witness to much of the region’s upheaval in the centuries since.

Although it now sits along the Syrian-Turkish border, Hatay’s geography is a point of contention. For nearly a hundred years, the two countries have disputed the province’s sovereignty, although the internationally recognized border puts it in Turkey.

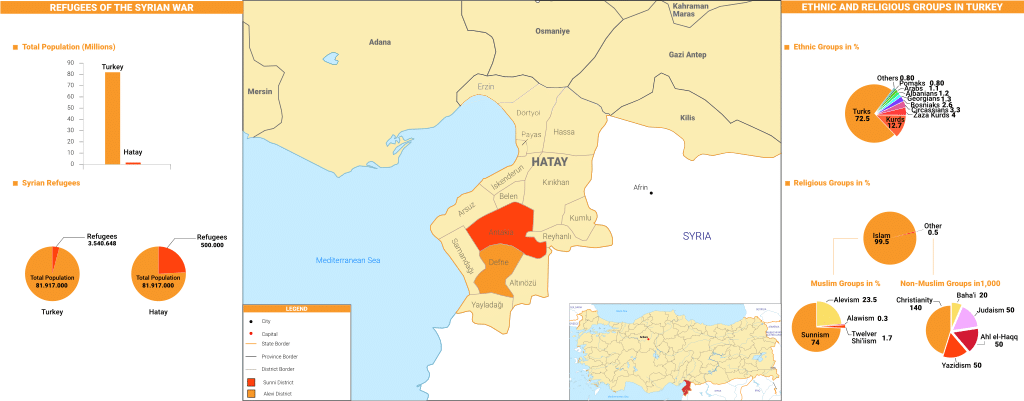

Today, the province is one of the country’s most ethnically diverse, counting Arabs, Turkmen, Turks, Christians and Kurds among its population. In recent years, hundreds of thousands of refugees from Syria have also made it home. Although the border has largely protected the province from the violence in Syria, it has not been spared the sectarian blowback from the war.

Loyal to al-Assad?

Hatay has long had a reputation for being one of Turkey’s most tolerant regions and is home to nearly a third of the governorate’s Alevi Shiites. The Alevis are often conflated with Syria’s Alawites, and although they are by no means identical, they both stem from the Shiite branch of Islam. As such, when the war in Syria broke out, ethnic tensions in Hatay flared as Sunnis, Turkey’s dominant demographic, denounced the abuses of the Alawite regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Some in Turkey began to question the loyalty of the Alevis, who have long been discriminated against by Ankara.

That said, the Alevis typically support Syria’s Alawite regime over the largely Sunni insurgency. Several pro-al-Assad groups are active in Hatay, even organizing rallies for the Syrian president, ostensibly under the banner of ‘anti-imperialism’. One such rally in late 2012 drew more than 10,000 people.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has helped to fuel these divisions. As the war in Syria spread and Sunni-Alawite tensions in Turkey grew, he repeatedly accused Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the opposition People’s Republican Party (CHP) and an Alevi, of being a supporter of al-Assad, whose Alawite family has dominated Syrian politics for decades.

Admittedly, the CHP has had warmer ties with the Syrian regime than Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) and has championed a stance more akin to the ‘zero problems with neighbours’ policy of the early AKP government.

A poll of the 2011 election showed that some 83 per cent of Alevis in Hatay voted for the CHP, adding weight to the suggestion that it is in the AKP’s interest to destabilize the current balance of political power in the province.

Political Meddling

Ankara has appeared to do just that. In 2013, it redrew the governorate’s boundaries, grouping the Alevi districts together under one name, Defne, with the remaining Sunni districts falling under Antakya. The grouping, which the authorities explained as merely bureaucratic simplification, was widely criticized as an attempt to stoke sectarian tensions.

Erdogan has also drawn criticism on numerous occasions in the wake of terror attacks for highlighting the Sunni faith of the victims. In May 2012, after two car bombs exploded in Reyhanli in Hatay, he denounced the killing of “53 Sunni citizens”, angering locals in the mixed-ethnicity town with his explicit sectarian message. Sectarian divisions, even with the country’s Kurds who make up some 15-20 per cent of the population, will almost inevitably benefit the Sunni majority, and Ankara is evidently not above using these divisions to its advantage.

Many Alevis in Hatay have been suspicious of Ankara’s meddling in the province and feel that the settlement of thousands of Sunni refugees in the area is a calculated attempt to curb their political influence, particularly since the AKP does not have a strong ideological base there.

Not that Hatay locals do not already feel they have a reason to dislike their new neighbours. As is the case in Lebanon and Jordan, the public services in Hatay have struggled to cope with the influx of refugees. Schools and hospitals have both suffered, and tensions between locals and refugees has become wide-spread. In Hatay, which is far from the industrial centres spurring Turkey’s economic growth, a common complaint among locals is that Syrians receive cash each month from the United Nations or via the Turkish government while they get nothing.

Yet even with such fertile grounds for sectarian violence, Hatay has largely escaped the instability that has affected much of the region. The closest the province has come to war has, ironically, been the result of the Turkish government’s own actions.

A Province under Threat?

Aside from its internal dynamics, Hatay has attracted undue attention from Ankara for other reasons. Increasingly, the province has been seen as a new front in the war against the militants of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Typically, most of the fighting in this insurgency has taken place further east, especially towards the border with Iraq. However, as the war in Syria allowed Kurdish groups to take control of territory in their own name, the flow of arms across the border became much easier.

The Kurdish-controlled canton of Afrin sits just across the border from Hatay, raising fears of PKK incursions. In 2017, Ankara declared Hatay a special security zone, as the Turkish army conducted raids against Kurdish militants holed up in the Amanos Mountains. The threat posed to Hatay by the PKK and its Syrian affiliates was highlighted again in January 2018, when the Turkish army and Turkish-backed forces attacked Afrin. Whether the threat was exaggerated to justify the Afrin operation is difficult to say, but once again Hatay has found itself, through no fault of its own, on the sidelines of war.