Introduction

Syria is officially a democracy whose President is elected and governed by the rule of law and a Constitution that specifies citizens’ and officials’ rights and duties, including human rights. In reality, Syria is a police state in which the President and his family wield power through ruthless security and intelligence agencies whose key function is to root out and suppress dissent. Detention without charge or trial, torture, and disappearances are routine and practiced with impunity. The cabinet, Parliament, judiciary, and media are all essentially creatures of the regime.

Syria was a parliamentary democracy, albeit a limited one, until 1958, when it merged with Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt to form the United Arab Republic (UAR). In the UAR, the ruling Arab Socialist Union was the only lawful party, and state security agencies wielded increasing power. Syria’s evolution into a full-fledged police state accelerated after the March 1963 coup that brought the leftist and nationalist Baath Party to power, and especially after the coup – officially termed the Corrective Movement – in November 1970 by Hafiz al-Assad, then Defence Minister and a leading figure in the pragmatic wing of the party.

Al-Assad brought all state organs under his and his family’s personal control and greatly expanded the military and the feared security agencies. Even the Baath Party became little more than an agent of the President, shedding all but a rhetorical adherence to its former ideology.

Hafiz al-Assad died in June 2000, having ensured that his son, Bashar, would succeed him. Although the political atmosphere lightened in the period after Bashar assumed the presidency, the repression apparatus remains firmly in place.

While the regime claims to be broadly based, its core comes from Syria’s minority Alawite community. Comprising about 12 percent of the country’s population, estimated at 22.5 million in mid-2012, the Alawis are a heterodox Shiite sect whose members live mainly in the north-western coastal mountains. The regime is, nevertheless, avowedly secular, and, as such, has enjoyed support from minority communities, including Christians and various other Shiite sects (including Druze and Ismailis), who fear rising Islamist sentiment amongst the country’s Arab Sunnis, who comprise perhaps 65 percent of the population.

The Constitution

Despite the realities, the regime assiduously nurtures essentially mendacious narratives to justify its continued relevance: that it represents the people and governs by popular assent, that it is the guardian of national unity and Arab nationalist aspirations, and that it is a bastion against Western ‘imperialism’ and Israeli expansionism.

Central to these attempts to confer legitimacy upon itself have been national constitutions promulgated in 1973 and 2012, which, especially in the 2012 document, were crafted to appear to define and limit regime powers while actually doing precisely the opposite. Syria achieved independence from France in 1946, with a Constitution based on the 1930 Constitution, imposed during the French mandate. New or amended Constitutions or re-adoptions of previous Constitutions were promulgated in 1950, 1953, 1954, 1958, 1962, 1964, 1969, 1971, 1973, 2000, and 2012. These changes closely reflecting changes in the regime in Damascus.

The 2012 Constitution is an amended version of the 1973 document, which was put in place by President Hafiz al-Assad. The 1973 document enshrined the ruling Baath Party, led by the President, as ‘the leading party in the society and the state,’ a clause that first appeared in the 1969 temporary Constitution; it concentrated power in the hands of the President. Echoing Baathist rhetoric, the 1973 document defined Syria as a part of the Arab nation, whose goals were ‘unity, freedom, and socialism.’

It asserted that ‘the revolution in the Syrian Arab region is part of the comprehensive Arab revolution’ and that ‘the march toward the establishment of a socialist order, besides being a necessity stemming from the Arab society’s needs, is also a fundamental necessity for mobilizing the potentialities of the Arab masses in their battle with Zionism and imperialism.

Constitutional Referendum 2012

The present Constitution was one of a series of responses by the authorities to a pro-democracy uprising that began in March 2011 and evolved, in large part, into an armed insurgency.

The new Constitution ostensibly seeks to introduce democracy and pluralism and to end the monopolistic grip on power of the Baath Party and the al-Assad family. It largely drops the revolutionary rhetoric of the 1973 Constitution, instead of defining Syria as ‘a democratic state’ whose ‘people (…) are part of the Arab Nation’ and as a country with ‘multiple religious sects.’

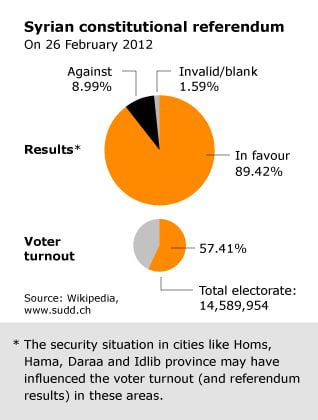

The Constitution asserts that ‘the political system is based on the principle of political pluralism, and the rule is only acquired and exercised democratically, through voting.’ It limits presidents to two seven-year terms. The Constitution was the subject of a referendum on 26 February 2012. Two days later, it was announced that 89.4 percent of the vote had been in favor, and President al-Assad promulgated the document the same day.

Opposition to the Constitution

Syria’s opposition movement, which urged Syrians to boycott the constitutional referendum, is deeply skeptical, condemning the new Constitution as a sham designed to enable the embattled regime to retain power under the guise of democracy. Critics note that the document includes a ban on retroactive legislation, implying that the 14-year limit on presidential terms might enable President Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father in 2000 and whose present term expires in 2014, to remain in office until 2028.

They point to Article 8(4), which stipulates that ‘No political activity shall be practiced. No political party or group formed on a religious, sectarian, tribal, regional, or professional basis or according to discrimination based on sex, origin, race, or color.’ This, they observe, effectively perpetuates the existing bans on the Sunni Islamist Muslim Brotherhood, which is almost certainly the largest political current in the country and various Kurdish parties.

Skeptics also point to Article 60, which stipulates that at least half of the assembly members (Parliament) should be workers and farmers, as defined by law’. They observe that the state rigidly controls Syria’s workers’ and peasants’ associations, ensuring that regime loyalists will dominate parliament.

Also, the President would, under the new Constitution, retain broad powers. He ‘lays down the state’s general policy and oversees its implementation, can draft laws, and assumes legislative authority when Parliament is not sitting. The President can also declare war or a state of emergency: Article 114 of the new Constitution affirms that ‘in case of the grave danger that threatens national unity or the safety and independence of the homeland or hinders the state’s institutions from undertaking their Constitutional duties, the President may take prompt action required by the circumstances to face the danger.’ Skeptics assert that this potentially gives the President carte blanche to act as he pleases when he feels that his regime is threatened.

The Constitution includes a series of ringing commitments to personal freedoms, for example, that ‘freedom is a sacred right, and the state shall guarantee the personal freedom of its people and safeguards their security and dignity; that ‘homes are protected and shall not be entered or inspected except by order of judicial authority and in the cases specified by law’; that ‘citizens have the right to assemble and demonstrate peacefully’; and that ‘it is prohibited to torture or treat anyone in a humiliating manner.

Critics observe that the 1973 Constitution, which did nothing to protect

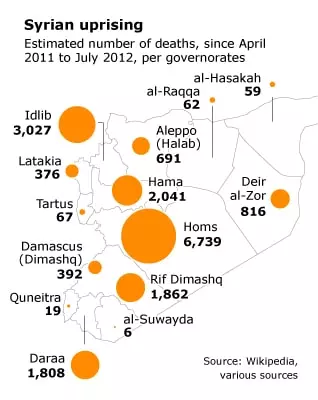

Syrians from the ravages of Hafiz al-Assad’s secret police contained similar high-sounding provisions and that the same regime that introduced the 2012 Constitution had, since March 2011, been murdering, imprisoning, and torturing civilian pro-democracy activists and their families and destroying and looting their homes, with impunity, and that it continued to do so after the Constitution’s adoption. The United Nations envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, stated in April 2016 that 400,000 Syrians had been killed in the war.

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimated in December 2016 that more than two million Syrians had been wounded, and according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, 4.9 million Syrians have fled the country.

If the uprising in which Syria is presently mired ends with President al-Assad’s downfall, it is doubtful whether the 2012 Constitution will outlive the regime that sponsored it.

The Presidency

Since the Baathist coup of March 1963, Syria’s presidents have been dictators, with few checks on their powers. This has been especially so in Hafiz al-Assad, who seized power in November 1970, and his son Bashar, who has ruled since his father’s death in June 2000.

The unchecked power of the presidency and the habitual abuse of those powers to enhance the power and interests – including the President’s family’s economic and financial interests – have been major factors in the uprising and insurgency in which Syria has been engulfed since March 2011.

The President’s powers are ostensibly defined and limited by the 2012 Constitution, which affirms that presidents must be elected and may serve no more than two seven-year terms and that candidates for the presidency must obtain the written support of at least 35 members of the People’s Assembly (Parliament) and be approved by the Supreme Constitutional Court.

The President appoints and can dismiss Vice Presidents, the Prime Minister, and other ministers. He can issue ‘decrees and orders, provided that they accord with ‘the law.’ He oversees state policy and, with the approval of Parliament, he can declare war and states of emergency. He is ‘the military and the armed forces’ chief commander and takes all decisions related to this authority, though he may delegate some of them. The President can dissolve Parliament and issue laws while Parliament is dissolved, although, by a two-thirds majority, Parliament may subsequently amend or annul such legislation.

The President can present draft laws for approval by the People’s Assembly, and he promulgates the laws approved by the People’s Assembly. He may veto these laws but must accept them if the Assembly again approves them by a two-thirds majority.

President Bashar al-Assad was reelected on 3 June 2014 for a third seven-year term, despite widespread local and international criticism. President Bashar al-Assad was re-elected on 3 June 2016 for a third term of seven years, despite widespread local and international criticism. The elections had been run amid a bloody conflict that by 2017 had killed an estimated 400,000 people, internally displaced 6.3 million, and forced 4.9 million to flee.

The opposition, its Western allies, and Gulf Arabs denounced the process as a farce, arguing that no credible vote can be held in a country where great swaths of the territory are outside state control. Millions have been displaced by conflict.

Voting was held only in government-controlled areas, excluding large parts of northern and eastern Syria in rebel hands. At the same time, the war continued on election day, with the air force bombing parts of Aleppo and fierce fighting in Hama Damascus, Idlib, and Daraa.

The Executive

Officially, executive power in Syria is shared by the President and the cabinet. The reality, however, is that power is monopolized by the President and his family, as members of the cabinet and prime ministers are the President’s creatures. The Constitution accords a wide range of powers to the President.

Article 118 of the 2012 Constitution declares that ‘The cabinet is the state’s highest executive and administrative body. It consists of the prime minister, his deputies, and the ministers. It supervises the execution of the laws and regulations and the state machinery and institutions’ work.’

Article 128 stipulates: The cabinet has the following powers:

- Formulating executive plans to carry out the state’s general policy.

- Steering the work of the ministries and other state’s public departments and establishments.

- Drawing up the state’s general budget project.

- Preparing draft laws.

- Preparing the development plan, developing production, and exploiting national resources and everything will strengthen the economy and increase the national income.

- Contracting and granting loans per the provisions of the Constitution.

- Concluding agreements and treaties per the provisions of the Constitution.

- Following up the enforcement of the laws, preserving the state’s security, and safeguarding the citizens’ rights and the state’s interest.

- Issuing administrative and executive decisions following laws and regulations and supervising their implementation.

Article 129 affirms: The Prime Minister and the ministers discharge the duties mentioned invalid legislation, provided they are not in conflict with the powers given to other state authorities by this Constitution. In effect, this means that if there is a potential conflict between ministerial and presidential prerogatives, the President will take precedence.

The Legislative

Syria’s legislative is the single-chamber, 250-seat People’s Assembly, or Parliament. Officially, elections are held every four years ‘by public, confidential, direct, and equal voting,’ in the words of the 2012 Constitution.

Article 75 of the 2012 Constitution affirms that the People’s Assembly assumes the following powers:

- Approval of laws.

- The debate of cabinet policy.

- Withholding confidence in the cabinet or a minister.

- Approval of the general budget and account audits.

- Approval of development plans.

- Approval of international treaties and agreements connected with state security; namely, peace and alliance treaties, all treaties connected with the rights of sovereignty or agreements that grant concessions to foreign companies or establishments, as well as treaties and agreements that entail expenditures of the state treasury not included in the treasury’s budget, and treaties and agreements that relate to granting loans or that run counter to the provisions of the laws in force or treaties and agreements that require the promulgation of new legislation to be implemented.

- Approval of general amnesty.

- Acceptance or rejection of the resignation of a member of the Assembly.

In Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, however, free and fair elections occur only within narrow limits. The 2012 Constitution stipulates that ‘No political activity shall be practiced and no political party or group formed on a religious, sectarian, tribal, regional, or professional basis or according to discrimination because of sex, origin, race, or color.’ This effectively perpetuates the existing bans on the Sunni fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood, which is almost certainly the largest political current in the country; and on a range of Kurdish parties.

Skeptics also point to Article 60, which stipulates that at least half of the assembly [Parliament] members should be workers and farmers, as defined by law’. They observe that the state rigidly controls Syria’s workers’ and peasant associations, ensuring that regime loyalists will dominate parliament.

The Baath Party – defined in the 1973 Constitution although not in that of 2012 as ‘the leading party in the society and the state’ – has overwhelmingly dominated the People’s Assembly for decades, operating as part of a so-called National Progressive Front (NPF), which also includes a handful of leftist and nationalist parties, all of them small and ineffectual. Indeed, no other political parties were legal in Syria. As a result, the Assembly has been entirely ineffective as a check on presidential power. Its main function has been to rubber-stamp and provides a veneer of legitimacy to regime decisions.

The Judicial

Syria’s judicial system dealing with non-political matters draws loosely on Islamic Sharia law (the 2012 Constitution stipulates that ‘Islamic jurisprudence is a major source of legislation’), based on Ottoman legislation and, especially, on the French legal tradition. The Ministry of Justice oversees civil and criminal courts. Defendants are presumed innocent. They may appoint their legal representatives and can confront their accusers in open court. Judgments may be appealed first to provincial courts of appeal and ultimately to the Damascus-based Court of Cassation or Supreme Court.

A separate Administrative Court, located in the Mezzeh district of western Damascus, sits to adjudicate disputes over the country’s bureaucracy’s decisions. Personal and family status matters, including marriage and divorce, are adjudicated by religious courts serving each of Syria’s religious faiths. For example, certain matters – marriage and inheritance – are subject to national law but are regulated through these religious courts. The customs of each religious community are generally respected.

On paper, Syria’s 2012 Constitution guarantees that justice will be dispensed freely and fairly by a judiciary that operates independently of the government administration. Article 132 of the Constitution affirms: ‘The judicial authority is independent. The President of the Republic guarantees this independence, with the Higher Council of the Judiciary’s assistance.’ Article 134 declares: ‘Judges are independent.

They are subject to no authority except that of the law’, and that ‘the honor, conscience, and impartiality of judges are guarantees of public rights and freedoms.’ Article 138 affirms: ‘Refraining from the implementation of judicial decisions or disabling that implementation is a crime punishable under the provisions of the law.’ Article 139 stipulates that ‘the law defines the terms of appointment, promotion, discipline, and removal of its judges.’ However, rather than giving the game away, Article 133 of the Constitution declares: ‘The President of the Republic presides over the Higher Council of the judiciary (…). The Higher Council of the Judiciary ensures the provision of the necessary guarantees to protect the judiciary system’s independence.’

In short, judicial independence is ‘guaranteed’ by the President, despite Syria’s Baathist presidents’ record of acting arbitrarily and unlawfully; and, despite all the assertions of judicial independence, the Higher Judicial Council, comprising senior civil judges, which appoints, transfers and dismisses judges (and which is charged under the Constitution with ‘assisting’ the President in guaranteeing the independence of the judiciary) is presided over by none other than the President.

The US State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Syria 2010 says: ‘The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary, but courts were regularly subject to political influence. According to observers, approximately 95 percent of judges were Baathists or closely aligned to the Baath Party.’ Especially in judicial matters relating to political dissent and regime security, the reality is vastly different from the fictions of regime propaganda. For these matters, a parallel and infinitely more powerful judicial system exists.

At least until April 2011, when it was repealed, at its heart, was a state of emergency that had been in effect, without interruption, since late 1962. It effectively gave the regime and its security agencies carte blanche to behave without even a pretense of due process. Under the state of emergency, violators were tried by military courts, and subsequent legislation built on this. Decree No. 6 (1 July 1965) established exceptional military courts, which had even fewer safeguards for defendants and used mainly as arenas for political causes.

The decree also created vaguely worded categories of crime, including ‘actions considered incompatible with the implementation of the socialist order, whether they are deeds, utterances, or writing’; ‘offenses against the security of the state’; and ‘opposing the unification of the Arab states or any of the aims of the revolution or hindering their achievement.’ In March 1968, Decree No. 47 replaced the exceptional military courts with a Supreme State Security Court (SSSC) to try political and security cases and an Economic Security Court to deal with financial crimes.

The decree explicitly stated that the new courts’ procedural rules would not be ‘confined to the usual measures’ that apply to civil courts. Middle East Watch (a precursor of Human Rights Watch) noted in a 1991 publication (Syria Unmasked: The Suppression of Human Rights by the Asad Regime) that ‘evidence could be introduced that had no ordinary standing in law, such as hearsay or even the opinion of the prosecutor.’ It added that, as there were no procedure rules, ‘there could never be an appeal on procedural grounds. A further type of special court, the military field tribunal, was created by Decree. No. 109 (1968) stated that such tribunals could be established anywhere during ‘armed confrontation with an enemy.

In practice, they have been used almost exclusively to dispose of the regime’s domestic enemies, notably during the repression of the armed uprising of 1976-1982. Middle East Watch (Syria Unmasked, 1991) summed up the progress of Syria’s legal system during the Baathist period: ‘Through a series of steps begun under the initial State of Emergency Law and continued through decrees and administrative action, the regime moved from a modicum of legality to a total disregard for legality; from courts to summary courts, to no courts.’

By presidential decree (21 April 2011), issued in response to the anti-regime uprising, the emergency law was repealed, and the Supreme State Security Court and Economic Security Court were abolished. There appears, however, to have been a scant impact, not least because most of the regime’s repression involves brutal violence that has no pretense of legality and because the military field tribunals, by which civilian dissidents can be tried, persist.

In addition to the normal civil and criminal courts and the security-related courts, Syria has a Supreme Constitutional Court. Like every other entity in the country’s political and administrative system, the Supreme Constitutional Court is a creature of the regime and, in particular, of the President. The 2012 Constitution stipulates that this court, which rules solely on electoral disputes and the constitutionality of laws and decrees, should comprise seven members, ‘all of whom are appointed by the President of the Republic, by decree.’ It sets a four-year renewable term for the court’s members.

State of Emergency

Article 114 of the 2012 Constitution affirms that ‘in case of grave danger which threatens national unity or the safety and independence of the homeland, or hinders the state’s institutions from undertaking their constitutional duties, the President may take prompt action required by the circumstances to face the danger.’

The President’s power to declare states of emergency, whether formally or under Article 114, has a special resonance in Syria. On 22 December 1962, shortly before the March 1963 Baathist coup, the former regime declared a state of emergency. This was reaffirmed in Military Command No. 2 by the Baathist regime on the day it seized power, 8 March 1963, and formalized the following day in Legislative Decree No. 1.

This gave extraordinary powers to a presidential-appointed martial law governor (the Prime Minister) and his deputy, the Interior Minister. They may restrict freedom of movement and assembly, including the preventive arrest of anyone ‘suspected of endangering public security and order’; censor letters and other communications, publications, and broadcasts; seize property; and close media organs. The law lists five categories of offenses: contravention of orders from the martial-law governor; offenses ‘against the security of the state and public order; offenses ‘against public authority’ offenses ‘that disturb public confidence’; and offenses that ‘constitute a general danger.’

The state-of-emergency law was promulgated despite contemporary constitutional requirements that states of emergency be approved by two-thirds of the cabinet and be submitted to Parliament. The state of emergency was justified officially as necessary to counter the military threat from Israel. In reality, its purpose was to protect the regime from internal dissent. It freed the Baathist state’s security agencies to sidestep all constitutional and legal protections and to crush dissent – however mild – ruthlessly, violently, and with impunity.

As one of the so-far futile measures to undermine the uprising that erupted in Syria in March 2011, the state-of-emergency law was repealed on 19 April 2011. The same day, the government issued new laws legalizing peaceful demonstrations, requiring that they receive permission, in advance, from the Interior Ministry – and abolishing state security courts. The measures were the subject of decrees issued by President al-Assad two days later. However, the ending of the nearly 50-year state of emergency has had no discernible effect on the conduct of the regime’s security agencies. They have continued to detain, torture, and kill with impunity.

Corruption

Like all sectors of Syria’s public administration, Syria’s judicial system suffers endemic corruption. For the same reasons: low salaries; appointments resulting from political and family contacts and favoritism, rather than professional merit; and general demoralization. The US State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Syria 2010 states:

‘The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption; however, the government did not implement the law effectively (…). Notwithstanding the investigation and dismissal of mid-and low-level officials’ scores for corruption during the second half of 2010, many other officials continued to engage in corrupt practices with impunity (…). Human rights lawyers and family members of detainees (…) cited solicitation of bribes for favorable decisions and provision of basic services by government officials throughout the legal process in both courts and prisons.’

As Muhammad Aziz Shukri, a former dean of Damascus University’s Department of International Law and a member of the committee that drafted the 2012 Constitution, has stated:

‘Until the United Arab Republic [the 1958-1961 union with Egypt], the Syrian judiciary was one of the cleanest, strictest, most objective judiciaries in the Middle East. Now it is one of the dirtiest, most unskilled, and definitely corrupted (…). I know of some lawyers who know nothing about the law but who win all the cases. And I know that these lawyers – I’ll refrain from mentioning names – receive one million Syrian Pounds [USD 19,230 at the 2002-2003 exchange rate] as a down-payment. These lawyers deal with drug trafficking, murders, conspiracies against the state (…), the massive, heavy cases (…). [Corruption existed in] all the courts, even in the so-called military courts (…). The overwhelming majority of the good judges are either in retirement or they have been released from their work.’

Parliamentary Elections

In the 2007 parliamentary elections, in which the turnout was officially recorded as 56.1 percent, the Baath Party and other parties of the National Progressive Front (NPF) won 169 seats, while 81 seats went to independents. These latter were not members of any NPF party, although their candidacy still had to be approved by the authorities; many of them, including businessmen and professionals, were strong supporters of the President.

The latest parliamentary elections were held on 7 May 2012, following the new Constitution’s adoption the previous month. The legislature’s term had expired in March 2011. Still, elections originally scheduled for May 2011 were delayed until February 2012 and then, again, until May 2012, because of the uprising in March 2011. The May 2012 poll was the first to be held under Syria’s new constitution, allowing political parties other than the Baath and its NPF allies. Nine new parties contested the elections and the Baath Party and the NPF, although their programs were difficult to discern, and their leaders were previously unknown.

None of Syria’s major opposition parties, including the banned Muslim Brotherhood and various Kurdish parties, was able to take part, and the opposition denounced the election as a sham and urged a boycott. Meanwhile, in large areas of the country, voting was impossible because of sieges imposed by the regime and violent clashes between government forces and rebels, and there were allegations of substantial fraud. None of this prevented the authorities from hailing the election as a major step in transforming Syria into a multi-party democracy.

On 15 May 2012, the Election Commission announced that the turnout was 51.3 percent. While the names of successful candidates were given, their party affiliation was not. This was a sharp break with the usual practice, prompting puzzlement expressions even from commentators in the state-controlled media. However, the Election Commission did state to no one’s great surprise that the so-called National unity List, comprising the Baath Party and six allied parties, had defeated the main rival grouping by a large margin Popular Front for Change and Liberation.

Parliamentary Tradition

Syria has a long parliamentary tradition, going back to 1919 and extending through the French mandate period. The country became independent in 1946 as a parliamentary democracy, albeit one in which political life was overwhelmingly dominated by a few traditional notable families from the main cities. In the early years of independence, there were four main seculars, ‘modern’ political parties: the Baath Party; the Communist Party; the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), which advocated the unity of Greater Syria; and the Arab Socialist Party (ASP), formed in 1950 by Akram al-Hourani and drawing support from the Sunni peasantry in the central plains. In 1952 the ASP merged with the Baath to form the Arab Socialist Baath Party.

Parliament was dissolved at the time of the military coups of 1949, staged by Husni al-Zaim on 30 March, Sami al-Hinnawi on 14 August, and Adib Shishakli on 19 December, but was reinstated in 1954 following Shishakli’s overthrow in another military coup, on 27 February that year. In the 1954 elections, the Baath Party won twenty-two seats out of the 142 in Parliament. During the 1958-1961 union with Egypt, a joint National Assembly functioned, with 200 members from the Syrian ‘Northern Province’ of the United Arab Republic. However, Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser monopolized real power, and the Parliament was correspondingly impotent. After the Syrian secession from the unified state in 1961, the Assembly was shut down.

The first Parliament in the Baathist era was a National Council appointed in 1965, two years after the coup, but dissolved after the 1966 counter-coup. That body included key party leaders, representatives of the armed forces and trade unions, the Peasants’ Union, the Women’s Union, and professional associations. It also included ‘progressive citizens,’ some from Baath Party splinter groups and the Syrian Communist Party (SCP), and some acting as individuals.

President Hafiz al-Assad appointed his first Parliament, 173 members, in February 1971, four months after his putsch, or Corrective Movement, as it is officially known. Its composition was similar to that of the earlier National Council. Still, it was broadened to include representatives from the leftist political parties that were later linked in the National Progressive Front (NPF) and from the main religious establishments and chambers of commerce and industry.

Setting the tone for parliamentary life’s style and substance ever since this, Parliament promptly nominated Hafiz al-Assad as the sole candidate for the presidency. His nomination was approved by 99.2 percent of voters in a national referendum on 1 March 1971. The same appointed Parliament overwhelmingly adopted a new constitution on 31 January 1973, which, like the Constitution of 2012, was likewise overwhelmingly approved in a national referendum.

Muslim Brotherhood

There has been a series of violent incidents involving the outlawed Sunni Islamist Muslim Brotherhood and the – largely Alawite – military. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, uprisings held or supported by the Muslim Brotherhood in Aleppo, Homs, and Hama led to heavy-handed repression and much bloodshed. In 1982, in a siege that lasted a month, Alawite troops completely destroyed the historical center of Hama’s city, killing thousands – estimates range from 3,000 to 20,000 – of mostly civilians.

The uprising was not necessarily religiously motivated. Numerous economic problems and strong criticism of Syria’s (foreign) policy also played a role, especially criticism of its conduct in the Lebanese Civil War (the support Syria gave to the Christian (Maronite) dominated government and its attacks on Palestinian resistance organizations). The whole situation led to cracks in the army, with Alawite and Sunni soldiers fighting one another – not only in the barracks in Hama and Homs but even in Lebanon, where Syrian troops were supposed to act peacekeepers.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s membership is punishable by the death penalty, which has been pronounced more than once but never put into practice; it is generally commuted to long prison sentences. Their leader, Ali Sadr al-Din al-Bayanuni (also known as Ali Saddredine al-Bayanouni), fled to London; there, the Brotherhood is trying to negotiate its return to Syria, so far with mixed success. Some ‘brothers’ have been allowed to return – on the condition they swear off their membership – but this has not always protected them from imprisonment.

Legal System and Framework

The Syrian legal system is based on a combination of Ottoman and French civil law. Article 3 of the Constitution states that Islamic jurisprudence is a main source of legislation. Sharia law is not applied except in some Muslim courts for personal status issues. There are different courts for Druze Muslims, Christians, Jews, and people belonging to other religions.

Article 131 of the Constitution states: ‘The judicial authority is independent. The President of the Republic guarantees this independence with the Higher Council of the Judiciary’s assistance. Moreover, Article 133 insists that ‘(1) Judges are independent. They are subject to no authority except that of the law and (2) The honor, conscience, and impartiality of judges are guarantees of public rights and freedoms.’

Finally, according to the Constitution (Article 28): ‘Every defendant is presumed innocent until proven guilty by a final judicial decision. This article also states: No one may be kept under surveillance or detained except following the law. No one may be tortured physically or mentally or be treated in a humiliating manner. The law defines the punishment of whoever commits such an act. The law safeguards the right of litigation, contest, and defense before the judiciary.’

Legal Framework

In February 2008, the International Labour Organization (ILO) wrote that although the Syrian government has sought social protection for its workers, the existing social security system needs to be adapted to the new economic reforms to guarantee future financial sustainability. A further challenge is the extension of social security to the excluded majority in the rural and informal economies. A combination of policy instruments is needed: unemployment benefits for formal sector workers, public works, and a minimum benefit package for all workers, including those in the informal economy. (Source: ILO, Decent Work Country Programme, February 2008)

Indeed, the informal economy’s large number of jobs leaves the majority of workers without basic forms of social protection. However, the new law on social protection adopted in the spring of 2010 (published by Presidential Decree No. 17 and replacing the old laws of 1959 and 1962) is controversial. Its critics say that certain articles of this law lower rather than raise the protection of the workers. Article 65 allows an employer to fire an employee without giving a reason and a limited penalty.

Workers sacked under this article are entitled to compensation of two months’ salary for every year worked, provided the payment does not exceed the equivalent of 150 times the minimum monthly salary (SYP 6,000 or USD 130). Leaders of the General Federation of Trade Unions (GFTU) say most employees will not take their employer to court. Also, the lawmakers assume that sacked employees will find work easily, as the new flexibility is supposed to create jobs.

The critics of the law contend this while recognizing the need to update the country’s outdated labor legislation. MPs were disappointed that suggested amendments that would have strengthened workers’ rights (like the right to strike) were ignored.

On the other hand, the business community welcomes the law and stresses that it improves working conditions. Weekly working hours are now limited to a maximum of 48 per week – eight per day and five days in a row – and employees are also entitled to at least one day off every week. The law also sets annual holidays (fourteen days for staff who have been employed for less than five years, 21 days for staff employed for five to ten years, and 30 for staff employed for more than ten years).

Article 95 defines the workers’ rights and the employer’s responsibilities. Employees are now entitled to a salary raise at least once every two years, although the rate of the increase is to be agreed upon between the two parties in the work contract. Article 95 also says an employee has the right to equal opportunity, equal treatment, and non-discrimination, the right to maintain his human dignity and secure working conditions.

Also, the new law will establish dedicated courts to rule on disputes between employers and employees. The courts, located in each of the country’s fourteen governorates, will be staffed by three members, including a judge and a representative for both employers and employees.

Finally, the law stimulates the transfer of those working in the informal sector (estimated between 40 and 45 percent of the country’s economy) to the formal sector. So far, workers in the informal sector have been excluded from the social security system’s benefits, which provides those affiliated with it with basic health insurance for the worker and his or her family. The new law makes it compulsory for employers to register their employees with the social security system. Employers who do not comply will be fined.

Local Government

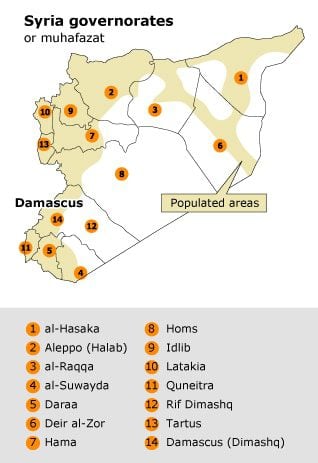

Syria is divided into fourteen governorates (muhafazat, singular muhafaza): al-Hasaka, Latakia, Quneitra, al-Raqqa, al-Suwayda, Daraa, Deir al-Zor, Damascus (Dimashq), Aleppo (Halab), Hama, Homs, Idlib, Damascus Countryside (Rif Dimashq), and Tartus.

Each muhafaza is headed by a governor (muhafiz) and an elected council. Governorates are in turn divided into districts (manatiq, singular mantiqa), headed by a kaymakam, and districts are subdivided into subdistricts (nawahi, singular nahiya), each headed by a mudir. Governors are appointed by the authorities in Damascus and are directly responsible to them.

Article 131 of the 2012 Constitution, dealing with local government, affirms the importance of ‘the principles of decentralization of the power and responsibilities. In much the same way that Syria’s Parliament and general elections are largely an exercise in political cosmetics, the country’s local administrative authorities wield little real power. In reality, this is heavily centralized in the President and his family’s hands and is projected throughout the country through brutal and feared security agencies known collectively as the Mukhabarat (‘intelligence’).

The Military

The Syrian army has traditionally been an important arena for the country’s minorities, offering employment and social advancement opportunities that have historically been denied them. However, minorities – the Alawites, Ismailis, Yazidis, Kurds, Christians, and Druze – have played unequal roles in several Syrian military coups. For instance, Alawites dominate the current Baathist regime and the military ranks, even though the coup that brought the Baathists to power in March 1963 was conducted by a military committee in which Alawites were in the minority. Sectarianism governed the military appointments made in the early days of the Baathist regime, despite claims contrary. Of the 700 military positions that became available following the coup, half of them were filled by Alawites.

The Armed Forces, when fully mobilized, number an estimated 750,000 men. By far, the army is the dominant element, with an estimated standing force of 300,000 men and reserves of 300,000 more. The other main branches are the Navy, Air Force, and Air-defence Force. Damascus has been closely allied with the Soviet Union and, after the USSR’s collapse, with Russia. Moscow has been the largest supplier of weaponry to Syria, providing everything from side-arms to fighter jets and naval vessels.

Illustrating how close the relationship is, Russia maintains a naval base in the Syrian port of Tartus, which is Moscow’s only such facility in the Mediterranean. In September 2015, the government asked Moscow to provide military support by conducting airstrikes inside Syria. Since then, an estimated 4,300 Russian forces have been stationed at the Hmeimim military base in Latakia province. By October 2016, the base had been equipped with the modern S400 rocket system. According to the Kremlin, the costs of Russian military operations in Syria to April 2016 were $0.5 billion.

The great majority of career soldiers, perhaps 70 percent, are Alawites, while most conscripts are Sunnis; the proportion of Alawites in the officer corps is even higher. The elite Republican Guard and 4th Armoured Division, which are the regime’s praetorian guards, are almost exclusively Alawite. Despite that, some notable exceptions exist. One of Hafez al-Assad’s closest allies for many years was Mustafa Tlass, a Sunni Muslim who served as deputy commander of the armed forces, vice president of the Council of Ministers, and defense minister from 1972 until 2004.

The Republican Guard, which Talal Makhlouf and numbers around 10,000 soldiers, is the only Syrian military unit allowed within the capital Damascus center. The 4th Armoured Division, under the de facto command of Maher al-Assad and based outside Damascus, has played an active role in the regime’s brutal efforts to suppress the pro-democracy uprising that has engulfed the country since March 2011. These two units are the best trained and equipped in Syria’s Armed Forces.

The Arab Spring

Since the outbreak of the pro-democracy uprising in Syria in March 2011, defections from the Armed Forces have become a major problem for the regime.

In April 2012 General Mustafa al-Shaykh, one of several army generals who have defected, claimed that some 50,000 soldiers had defected, many of them to join opposition fighters, especially the Free Syria Army (FSA). Official Turkish estimates reported in April 2012 put the number of defectors at 60,000 to 65,000, about 20 percent of the standing Armed Forces. General al-Sheikh also said that tens of thousands of Sunni soldiers had been confined to their barracks because their loyalties were suspect.

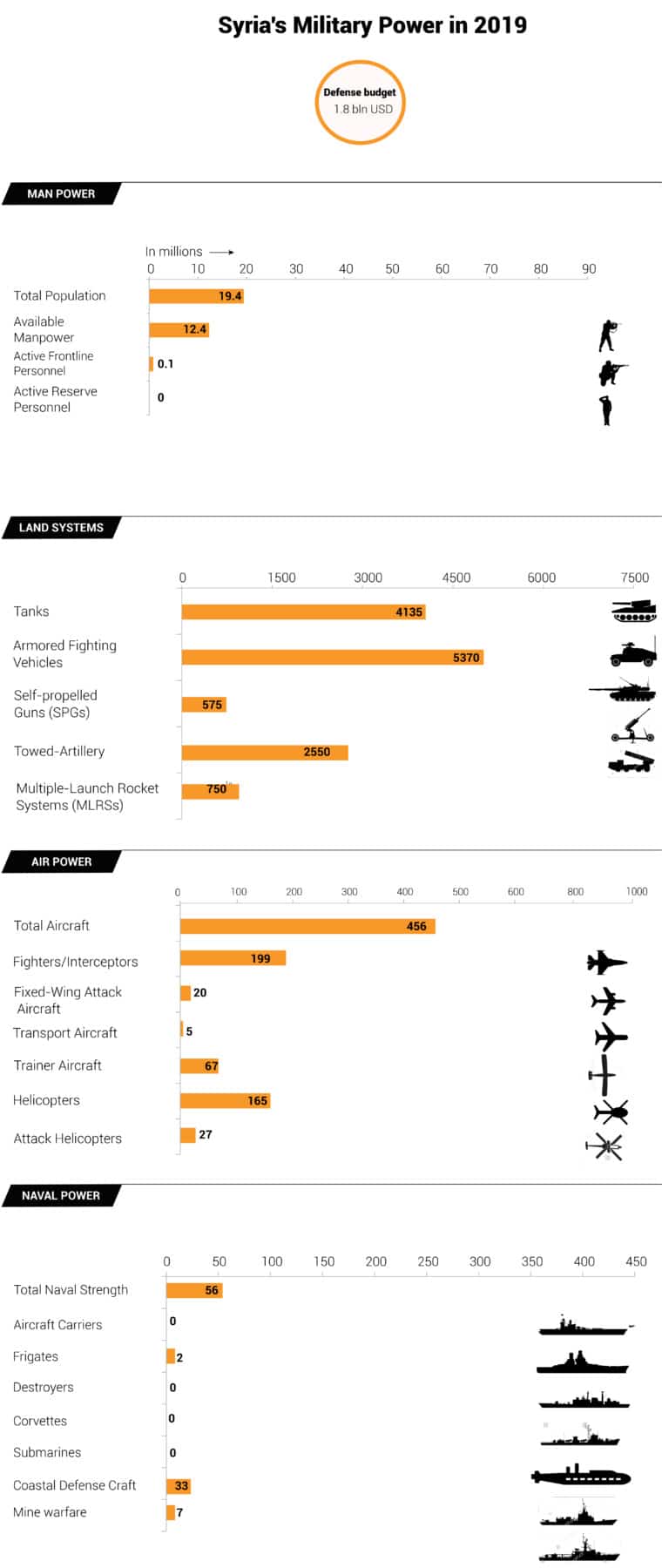

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 142,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 142,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 547 | 29 |

| Fighter aircraft | 200 | 15 |

| Attack aircraft | 133 | 21 |

| Transport aircraft | 4 | 50 |

| Total helicopter strength | 166 | 28 |

| Flight trainers | 67 | 41 |

| Combat tanks | 5,035 | 5 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 5,170 | 14 |

| Rocket projectors | 700 | 7 |

| Total naval assets | 56 | - |

| Frigates | 2 | - |

Syria’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

Defense budget

The magnitude of Syrian defense spending is unknown. As of 2011, the situation was summarized by the UK-based Jane’s organization. The Syrian Defence Minister presented a budget for FY11 that included the FY10 top-line information. The budget was approximately SP89 billion (SP – Syrian Pound) in FY10, growing to SP100 billion in FY11. Depending on the conversion rates, that translates into approximately USD 1.9-2.0 billion for FY10 and USD 2.2-2.4 billion for FY11.

No other details were available. Other estimates from various sources pin the budget to a much higher number (USD 6 billion). Jane’s has taken a slightly higher ground than the official Syrian publication and added about 10 percent to the minister’s proposal. That only equates to about 3.5 percent of the GDP. Some other sources suggest that expenditures are closer to 6 percent of GDP. This is the lowest level of Syrian defense spending since records dating to 1998. Therefore, Jane expects this to be an anomaly that will be adjusted upward over the next ten years.

According to globalfirepower.com, which ranks the world’s major military powers, the Syrian defence budget is $1.87 billion.

Military History

After an UN Commission advised the partition of the British Mandate of Palestine and the State of Israel was proclaimed in May 1948, Arab national armies intervened and joined the Palestinian and Arab militia, which conflicted with their Zionist and Jewish opponents. Syria attacked with some 2,000 men, supported by a handful of tanks and artillery, from the Golan Heights towards Lake Tiberias’ southern banks.

Israeli forces and local militia lightly defended the Syrians’ area, but for an important part, it was easily defensible urban terrain. Syrian forces slowly moved forward, not fast enough to prevent Israeli reinforcements from shoring up the defense. Syrian pinprick tank and air attacks failed to stem the tide of battle – which in any case could be better defined as skirmishes. Another small-scale Syrian offensive north of Lake Tiberias also failed to gain ground.

In the Armistice Agreement that Israel and Syria signed in July 1949, it was established that land east of Lake Tiberias would be Syrian but demilitarized. Syria started to fortify the Golan Heights overlooking rural Galilee and Jewish settlements. From there, now and then, artillery rounds were fired at Israeli targets down below. It is a documented fact this was in response to Israeli provocations.

June War 1967

With the June War outbreak in 1967, the situation of uneasy ceasefire and armed clashes that had existed since 1948 between Syria and Israel also escalated. In the long prelude to the war, the clashes between Israeli and Syrian forces already amounted to an undeclared war. After the Egyptian air force was destroyed on the ground by Israeli aircraft during the opening hours of the war, the Egyptians’ military assessment was less than accurate: they said the Israeli armed forces were mortally wounded. With this moral support, the Syrian military started to shell and bomb Israeli targets. The Syrian army divisions remained in their positions, however.

In the last days of the war, the Israeli army, which had been victorious in the Sinai and on the West Bank, prepared to occupy the Golan. Israeli ground forces attacked the Golan by escalating the escarpments, and the Syrian defenders were surprised by nightly helicopter landings on strategic positions. Threatened by encirclement, the Syrians’ Syrian morale dropped, and their forces started to retreat eastwards. An UN-brokered ceasefire left the Golan occupied by Israel.

October War 1973

The global perception of Arab military impotence based on the Israeli victory in the June War was shattered by the well-timed and coordinated surprise attack in October 1973 by the Egyptian and Syrian armies. It is not exaggerated to say that the Syrian armed forces posed the biggest strategic threat to Israel from the two attacking militaries. On 6 October 1973, the first day of the October War (also called Yom Kippur War or Ramadan War), a few hundred Syrian commandos helicoptered in on an important Israeli listening post on Mount Hermon, north of the Golan, that overlooked both Galilee and the roads leading to Damascus. They quickly overwhelmed the Israeli crew of the monitoring station. An Israeli counterattack on 8 October failed to reclaim the facility.

The Israeli troops on the Golan saw Syrian tanks down below towards their starting lines, and Syrian gunners ready their guns and rocket launchers. After an initial artillery bombardment on important Israeli positions around 800 T-54/55 and newer T-62 tanks started to climb the Golan Heights. Facing them were less than 200 Israeli tanks, mostly Centurions of two Israeli armored brigades. Syrian mobile air defenses succeeded in downing dozens of Israeli jets on attack missions to blunt the Syrian attack. The vastly outnumbered Israeli tanks profited, however from their prepared positions, the higher ground their marksmanship and succeeded in narrowly defeating the Syrian onslaught. They thus bought time for reserve units to arrive.

On 21 October, Israeli troops retook the listening post on Mount Hermon. An UN-brokered ceasefire ended hostilities.

Israeli Air Attack on Nuclear Site (2007)

On 6 September 2007, a strike package of Israeli combat aircraft attacked a northeast of Syria, allegedly a nuclear reactor built with North Korean technical support. Satellite imagery showed a large unfinished building with features reminiscent of the Yongbyon reactor in North Korea. Inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United Nations (UN) nuclear watchdog, visited the site, but they found the building site thoroughly bulldozed. Soil samples contained traces of enriched uranium, which Syria attributed to the Israeli bombardment.

The Military Post-2011

The bloody civil war, which began in 2011, continues to dominate Syrian daily life. The conflict has also left the military damaged and short of personnel. Allied militias fighting alongside conventional forces have played an important role in keeping President Bashir al-Assad’s regime from being toppled.

In 2019, Syria ranked 50 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 535,381 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $1.9 billion.

The “Arab Spring” that flashed through the Arab world beginning in December 2010 reached Syria that same year. Nonviolent demonstrations were followed by armed resistance against government forces, which has seriously degraded the Syrian military capabilities.

This can be attributed, in large part, to the loss of bases and airfields, but the defections of thousands of regular troops and officers have also played an important role. The lack of trustworthy fighters led to the government’s request for 8,000 to 10,000 Hezbollah fighters from neighboring Lebanon in 2013. It is estimated in October 2014 that 120,000 troops, at most, remain loyal to the Syrian government of President Assad.

Much of the fighting focused on Syrian army barracks and air bases, such as Taftanaz, Base 46, Hagana, and Meagh, that contained warehouses filled with weapons, ammunition, and another materiel. The capture of these bases would not only provide rebel groups much-needed weaponry and supplies. Still, it would also prevent government forces from launching airstrikes or artillery attacks from these locations. Fighters from different ideological backgrounds could frequently be seen waving automatic weapons while standing between stranded MiG and Sukhoi fighter-bombers of the Syrian Arab Air Force, making photo opportunities with excellent propaganda value.

In addition to confiscated arms, opposition groups were also supplied with materiel by Western and Arab supporters. The United States and, reportedly, the United Kingdom, among other countries, hesitantly provided “moderate” opposition groups such as the Free Syrian Army with training and (mostly) nonlethal equipment such as all-terrain vehicles, communication gear, and night-vision equipment. By September 2014, a significant influx of Western weapons and other stocks had failed to materialize. However, US President Obama has announced new initiatives in this area, pledging training in the region and weapons supplies to a total value of 500 million USD.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar reportedly did provide the more extremist groups such as al-Nusra Front and forces associated with Islamic State (IS) with sophisticated weaponry, such as Chinese FN-5 man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) and other equipment. Some of this was acquired abroad—for instance, in Croatia—and some of it presumably was taken from own stock, such as TOW wire-guided anti-tank missiles that appeared in videos shot by al-Nusra fighters.

The Syrian authorities, too, are supplied by foreign governments.

Security sources told Reuters at the beginning of 2014 that ‘dozens of Antonov 124 Russian transport planes have been bringing in armoured vehicles, surveillance equipment, radars, electronic warfare systems, spare parts for helicopters, and various weapons including guided bombs for planes’.

Russian military personnel was said to have been operating unmanned aerial vehicles ‘to track rebel positions, analyze their capabilities, and carry out precision artillery and air force strikes against them.’ Russian naval transports unloaded equipment in Latakia and Tartus.

Simultaneously, Iranian Boeing 747 cargo planes were flying supplies and, reportedly, advisors into Damascus airport daily.

Like other government forces in the region, the Syrian armed forces were lavishly equipped, with nearly 5000 tanks, for example, and 500 fighter-bombers. Whether many of these were operable even before the beginning of the current conflict is doubtful. More than half of these have probably been rendered inoperable due to battle damage, desertions, and rebels’ capture.

Chemical Weapons

Another noteworthy military development was the deployment and subsequent disposal of Syrian chemical weapons. After many rumors about their deployment, a large-scale attack with chemical substances took place in August 2013 on opposition-held neighborhoods in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta, leaving at least several hundred people dead and many more wounded.

Although the US president had called the use of chemical weapons a “red line,” whose crossing would mean armed intervention, no US airstrikes materialized, mainly due to negotiations with Russia, which had, in return, arranged that the Syrians would agree to dispose of their chemical stockpiles, which included mustard gas and sarin and VX nerve gases, totaling an estimated 1000 tonnes. Syria became a member of the UN’s Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

The destruction proved to be a difficult task, not least because many warehouses and associated equipment were located in areas no longer controlled by government forces.

A complex logistical organization loaded the most dangerous chemical weapons aboard a Danish vessel in Latakia that then proceeded, escorted by naval vessels, to the harbor of Gioia Tauro in southern Italy, where the chemicals were transferred to the American containership Cape Ray, which had been converted by the US Navy into a floating facility to neutralize the weapons chemically. A Norwegian ship loaded with precursors sailed a few months later to neutralizing facilities in Finland and the United States. The OPCW concluded in July 2014 that the operation had succeeded. However, it remains unclear whether all the stockpiles were taken out of the country—in other words, whether the Syrian government had made a ‘full and final disclosure.’

On 4 April 2017, more than 80 people were killed in a sarin gas attack on Khan Shaykhun, near Idlib. Some activists and eyewitnesses accused the Syrian regime of carrying out the attack. The army denied the accusations, and President Bashar al-Assad described them as “fabrications” to justify the US’s missile attack on the Shayrat airbase three days later.

Despite signing the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), Syria has a secret nuclear program, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. However, a reactor under construction in a remote area near Deir Ez-Zor was shelled by Israeli jet fighters in 2007, which effectively halted the program.

Security Agencies

Power in Syria is strongly centralized in President Bashar al-Assad and his family and is projected throughout the country through elite military units dominated by members of the President’s Alawite sect and brutal and feared security agencies known collectively as the Mukhabarat (‘intelligence’).

There are four main Mukhabarat agencies: the General Security Directorate, the Political Security Directorate, Military Intelligence, and Air Force Intelligence. These have overlapping functions and are all preoccupied less with Syria’s security than with the security of the regime, constantly monitoring the populace and detaining people with suspect loyalties. One Syria specialist has estimated that one in every 153 adult Syrians works for one or another of these agencies (Alan George, Syria: Neither Bread nor Freedom, p. 2). The Mukhabarat agencies, which operate with impunity, outside any legal constraints, are notorious for detainees’ maltreatment and torture.

All four agencies and their numerous subdivisions have been heavily involved in the regime’s bloody efforts to suppress the uprising that has engulfed the country since March 2011. Their directors and many of their senior officers have been subjected to international sanctions for human rights crimes.

In its vain efforts to quell the uprising, the regime has also deployed a ruthless, mainly Alawite militia known as the shabiha (said to be named after a Mercedes car model called shabah, or ‘ghost’). Before evolving into a more formal arm of the regime, the shabiha comprised street gangs, many of them members of the President’s clan, who had been a feature especially of Syria’s north-western coastal region (where the al-Assad clan is based) and who were notorious for their violence and criminality and could act with impunity.

Before the pro-democracy uprising of 2011, the shabiha’s influence had waned considerably due to security operations directed by Bashar al-Assad and his late brother, Bassel, in the 1990s. With the 2011 pro-democracy uprising, the shabiha have grown in numbers and influence and have repeatedly been used by the authorities as a militia to attack anti-regime protesters.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Syria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: