Experts believe that the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement could pave the way for political reconciliation in Lebanon, but they also note that a straightforward diplomatic agreement will not be sufficient to address the country's fundamental issues.

Dana Hourany

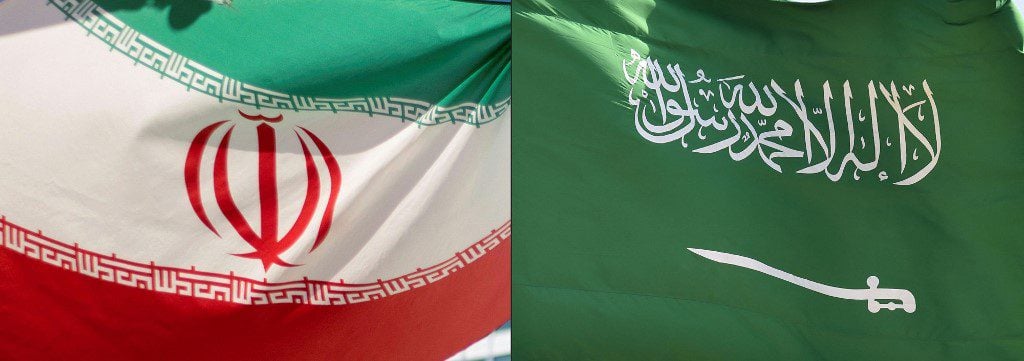

In the wake of the unexpected agreement to normalize relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia on March 10, both countries have been given a two-month deadline to demonstrate their commitment. During this period, they must prove that the collaboration is sincere on both sides.

Prior to any diplomatic relations being re-established formally, the two nations may be contemplating how to put an end to the many years of animosity. This is no small feat given the far-reaching consequences of such a decision, especially in Arab countries such as Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon, which have suffered the consequences by proxy.

In light of Saudi Arabia’s decision to concentrate on diplomacy and economic growth rather than conflict, and Iran’s increasing isolation, this freshly forged reconciliation may therefore be an effective choice for both nations. Experts and observers, however, say that their impact on a regional level – particularly in the Levant — may not be palpable immediately.

With Saudi Arabia supporting Lebanese Sunni politicians and Iran backing the powerful Shiite group Hezbollah, the long-standing rivalry between the two has shaped the political scene in Lebanon. Analysts have argued that reducing tensions between Riyadh and Tehran could pave the way for a possible political reconciliation in crisis-riddled Lebanon.

However, amid severe economic conditions and an unoccupied presidential seat, Lebanese Sunni and Shiite observers say they refuse to be taken in by unrealistic hopes for a quick fix, while experts contend that a straightforward diplomatic agreement will not be sufficient to address Lebanon’s fundamental issues.

The Saudi-Iranian conflict in Lebanon

Though the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has historically had strong ties with Lebanon’s Sunni Muslim community, represented by the prime minister under Lebanon’s sectarian system, its attempt at creating a powerful political proxy within the country never achieved the same level of success as seen with Hezbollah and Iran’s solid alliance.

This is partly attributable to the 2005 assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, once a significant ally of the kingdom and an influential instrument of Saudi sway in Lebanon.

Saudi Arabia made intermittent attempts to impose its influence in the aftermath, led by the assertive and strict strategies of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. However, due to its disjointed approach and unable allies, it was ineffectual to halt Hezbollah’s electoral rise in Lebanon. The Kingdom did not possess the adequate means to take action against the group and was forced to observe as they took over various governments.

Saad Hariri, a former prime minister of Lebanon, was called to appear on television from Riyadh and announce his resignation as a result of Hezbollah’s hegemony in 2017. This was Saudi Arabia’s biggest action to date. According to reports, he was summoned to Riyadh against his will, and forcibly detained.

Although Hariri rescinded his resignation upon returning to Lebanon, he failed to form a government in 2021, opting to resign from politics completely, leaving the Sunni community without a leader and without the strong formal representation that the Hariri-Saudi alliance provided.

In October 2022 strained ties between Saudi Arabia and Lebanon were further exacerbated when remarks by George Kordahi, the country’s then Information Minister, were broadcast. The previous host of a celebrity game show had joined the Lebanese cabinet just one month before his statement that deemed the Saudi-led coalition’s war in Yemen “futile” and argued that the Iranian-backed Houthis are merely “defending themselves against an external aggression.”

In the wake of that incident, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah accused Saudi Arabia of “terrorism” and attempting to start a civil conflict in Lebanon.

Iran, on the other hand, has used a variety of soft power initiatives to exercise control over Lebanon using a multidisciplinary strategy. Cultural, educational, media and informational endeavors coupled with religious and humanitarian activities have been geared towards increasing the ideological and political sphere of influence in Lebanon, particularly among the Shiite population.

According to the Middle East Institute, these actions are undoubtedly meant to bolster Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanon and support Iranian-Lebanese relations while concurrently fueling hostility toward Western powers like the United States and its allies, like Saudi Arabia.

What happens now in Lebanon?

Currently, the presidential elections are a key area of contention between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Prior to the March 10 agreement, Hezbollah asserted its support for Syria’s ally and Lebanese Maronite Christian, Suleiman Frangieh for president, whereas Saudi Arabia has unofficially rejected the candidate.

The Patriarch of the Maronite Church of Lebanon, Bechara al-Rai, received a visit from Walid al-Bukhari, the Saudi ambassador to Lebanon, on March 7 at his home in Bkerke, according to the local newspaper Al-Akhbar, to make it clear that Saudi Arabia was blocking Suleiman Frangieh’s candidacy.

Senior editor at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut and political analyst Michael Young told Fanack that Hezbollah may have been aware of the agreement prior to it being signed. Accordingly, their endorsement of Suleiman Frangieh placed them in a position where they would be able to leverage his candidacy as an advantage during post-agreement negotiations.

“If they knew a Saudi-Iranian deal was coming, and assumed this would impose a compromise arrangement over the presidency, it made sense for them to endorse Frangieh first,” Young noted. “In that way, they would enter possible negotiations over a candidate with a favorite in hand, to ensure they would receive a higher price to give him up.”

Reconciliations, he adds, are nevertheless a positive development. However, it is not likely that immediate results will be realized, since “major shifts cannot be achieved until all sides receive more or less what they desire on the presidential front.”

In his view, the presidential elections will come as a package deal containing an economic and political program, taking into account the views of all political sides.

Saudi Arabia, once a major investor in the country, contributing in large measure to the luxury tourism industry, has reduced its economic assistance in the last few years – a trend Young does not anticipate improving anytime soon.

“Who would wish to invest in a country with a failing financial sector?” Young asked. “The country is facing fundamental issues that must be resolved before large-scale investments return.”

The economic crisis in Lebanon has been described by the World Bank as one of the worst in history and is largely attributed to years of mismanagement by political leaders and corruption. The local currency has lost over 99 percent of its value against the US dollar with banks still locking people out of their dollar deposits.

Political influence in Lebanon

When it comes to shifting political influence in Lebanon, Young does not anticipate that Iran’s role will diminish soon. Rather, the agreement provides a greater opportunity to reach compromises but does not imply that Hezbollah will be ready to give up power.

“Ultimately, neither Hezbollah nor Iran will make any compromises that undermine their interests. So even if a compromise candidate is brought in, they will still safeguard their interests.”

Regarding Saudi Arabia’s role in the country – which has been significantly eclipsed by Iranian influence in recent years – Young does not foresee any significant changes there either.

“Essentially, the Saudis interpret the reconciliation with Iran as a good reason to consider Saudi interests in Lebanon. Riyadh and Tehran could reconcile today over a number of issues, and one manifestation would be to take Saudi interests into account in Lebanon, which would be a middle-of-the-road president that is not allied with either side,” Young noted.

He emphasizes that this does not mean that money will pour in immediately.

The political and social gap Hariri’s departure left in the Sunni community also doesn’t seem to have been substantially narrowed.

Without appropriate economic manifestations, the Sunni community has no interest in the agreement, according to Lara Harb, a 25-year-old erstwhile supporter of Saad Hariri.

“On the political front, I do not believe that a new Sunni leader will emerge, but rather that negotiations for a president may now be smoother.”

According to 28-year-old Ali Khanso*, Hezbollah supporters’ opinions of Saudi Arabia have not changed as a result of the deal.

Instead, he asserts that the news “hit with a sense of disappointment” among ardent supporters of Iran and Hezbollah.

“I doubt full support for Saudi Arabia will be expressed in the near future,” Khanso told Fanack. “To ease some of Lebanon’s political and economic burdens, though, this might be a step in the right direction,” he said.

“This might lead to less local animosity and demonization of Hezbollah because it has been largely blamed for the country’s present issues.”

However, he continues, “Hezbollah supporters in Lebanon will ultimately follow what the group’s leaders say rather than what Iran does on a regional level. Therefore, until Hezbollah openly declares a change of heart toward Riyadh, its proponents will not be easily persuaded.”