Dana Hourany

In 2018, Vinda Mohammad, 29, returned to her homeland city of Aleppo, Syria.

Her family had sought safety in Germany after fleeing the crisis that started in 2011. However, Mohammad’s home had always been Aleppo.

“People are curious as to why I returned,” Mohammad told Fanack. “But, to be honest, I didn’t realize how valuable Aleppo was until I had left.”

Mohammad returned to Aleppo and enrolled in a university to pursue a degree in Heritage and Archeology, after which she graduated and began working with “Raha,” an archaeological documentation, restoration, and rehabilitation firm.

Located in northwest Syria near the Turkish border, Aleppo was once Syria’s most populated city – known for its booming economy, historical landmarks, and traditional architecture.

War-torn heritage

Despite various efforts to rebuild and reconstruct critical portions of the city, experts say the process will be sluggish and unreliable, particularly if Aleppians are not fully present to oversee it.

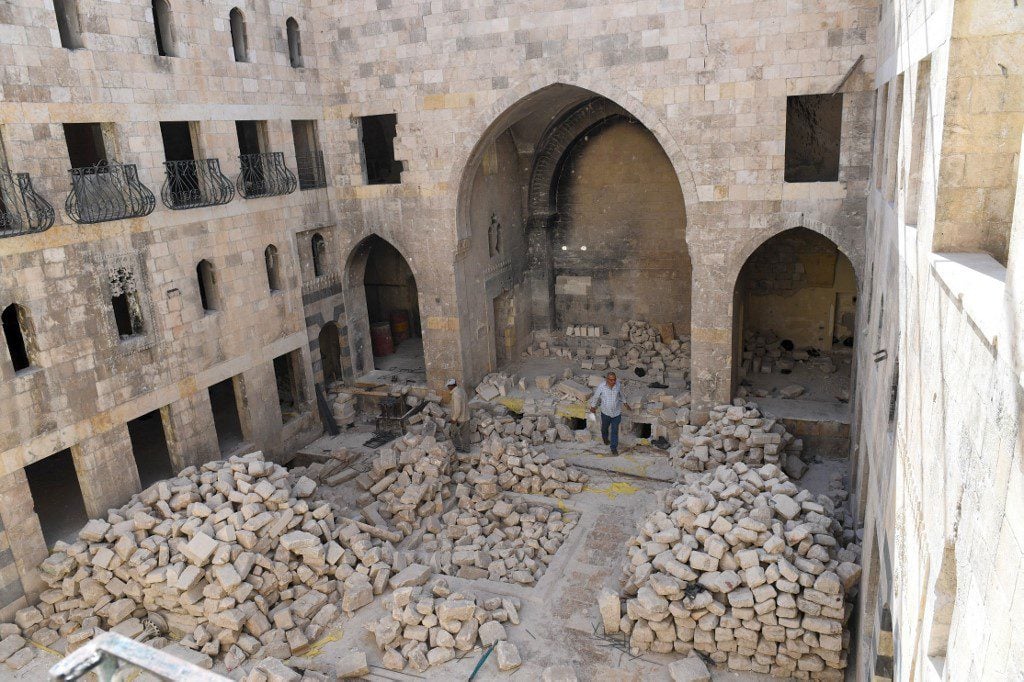

According to a 2019 research by REACH, a humanitarian organization that collects data from crisis situations, Aleppo contains approximately 36,000 damaged structures, while UNESCO believes that 60 percent of Aleppo’s ancient city has been seriously damaged, with 30 percent completely destroyed.

This was due to fierce fighting over the span of four years (2012-2016) when the city fell under the grip of rebel groups. The Assad regime responded by dropping barrel bombs, imposing an all-out siege, and denying even humanitarian aid, relying on military support from both Russian warplanes and Iranian proxy fighters. Overall, the Governorate of Aleppo saw the greatest number of documented killings, with 51,731 named individuals, according to the UN.

All commerce, enterprises, and industries that once made Aleppo Syria’s economic engine, came to a standstill as a result of the protracted conflict.

Rich history, rich city

“Every village has a road to Aleppo” is a common saying amongst Aleppians and “what is sold in Aleppo in a day needs months in other cities” was popularized after author Abraham Marcus noted it in his 1980s book, “The Middle East on the Eve of Modernity: Aleppo in the Eighteenth Century.”

The city was named Halab in Arabic after a four-thousand-year-old village called “Halabu,” and it displayed evidence of wealth from its inception. Cuneiform tablets indicate that the city was a center for clothing and textiles and that it even became the heart of the Silk Road in the wake of the advent of Islam in the medieval era.

According to World Monuments Watch, Aleppo’s souks (markets) had once been the throbbing core of the city for generations. Spices, traditional delicacies, textiles, carpets, and well-known handicrafts like Aleppian soap kept its people prosperous and self-sufficient.

The ancient city, which contains the famed citadel and marketplaces, was inducted into the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1986 due to the architectural marks left by the former empires of Hittites, Assyrians, Greeks, Romans, Umayyads, Ayyubids, Mamelukes, and Ottomans.

Furthermore, the city’s multicultural culture and spiritualism are reflected in a plethora of mosques, churches, Sufi shrines, and medieval Jewish treasures such as the Aleppo codex.

The city, on the other hand, is no stranger to conflict. Aleppo has bore witness to a myriad conflicts, from the Crusaders to the Mongol conqueror Timur, who “piled high a mountain of thousands of skulls outside the city gates.”

“It isn’t the first time Aleppo has been devastated and then resurrected. I have a lot of optimism for our city, as seen by the development that has been made thus far,” Mohammad said.

Slow and steady progress

Individual and group efforts are ongoing to preserve Aleppo’s history in a digital archive that will be accessible to the entire world.

One such initiative is the German Foreign Office’s online toolbox for the project “Urban Cultural Heritage in Conflict Regions,” which aims to assist stakeholders in navigating the needs for conservation and restoration alongside urban renewal for the Middle East’s war-torn ancient towns.

Compiling and displaying historical and contemporary information from different sources can be repurposed as a reference for reconstructing damaged cityscapes and supporting the assertion of ownership/property rights for displaced legitimate owners.

The reconstruction method is mapped out using 3-D photogrammetry, building information modeling (BIM), high-quality scans and 3D sculpting, and 3d visualized reconstruction.

Though online documentation work is active, on the ground restoration is proving slow and costly.

“Most tools used for the restoration works on the ground are general tools that are not advanced. The freefalling economy is also an important factor,” Mohammad said.

The restoration of the Al-Ahmadiyya and Al-Saqtiyya marketplaces, as well as significant churches and mosques, were all locally-led initiatives spearheaded by Raha, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, and local religious groups, with no foreign assistance, Mohammad adds.

“Markets are crucial for the economy … but we also need to restore the surrounding areas so that Aleppians have somewhere to dwell while they restart their enterprises.”

Hope amidst the chaos

Omaya Al-Saghir, a Lebanese architecture professor researching modern technologies for revitalizing destroyed ancient cities told Fanack that her preliminary observations of the city show that tourists are slowly flocking back to Aleppo’s streets.

On restoration efforts, Al-Saghir believes that contemporary materials do not detract from the city’s ancient validity, but rather contribute to highlighting its global significance.

“You may either keep the structures demolished or reconstruct them with other stones,” Al-Saghir told Fanack. “I support restoration so that the place’s meaning and worth be preserved despite the war’s horrors.”

As for the Citadel of Aleppo, Mohammad says that the “slight damage that was documented after the city was liberated was promptly dealt with.” Music concerts and festivals are currently being held at the monument.

The challenge of rebuilding Syria’s largest city will cost tens of billions of dollars, according to the Associated Press, and Western countries are unlikely to provide funding to Assad’s administration owing to US, European, and Arab sanctions prohibiting aid to the regime.

A shell of its former self, Aleppo and its remaining residents struggle with inflation, an unstable currency, and tough living conditions. Many families rely on multiple wages and humanitarian assistance to survive.

“At first it was heartbreaking to look at all the devastations that happened to my childhood home. But now, every time I visit Aleppo’s old city I feel alive again. The city has overcome devastation many times throughout history and I believe it will do so once again,” Mohammad said.