Introduction

The World Bank has classified Syria’s economy as having a lower middle income level within the region Middle East & North Africa. Syria’s economy is essentially state-run, although it has remained partly private, as for example the retail trade businesses.

Bashar al-Assad, who became President in 2000, started to privatize more sectors of the economy. Until recently, Syria had trouble attracting foreign investors, as 51 percent of a business’ capital had to be Syrian. In 2009, more reforms were announced, opening up the financial sector as well.

In many respects, Syria is still a poor country that relies heavily on help, mainly from rich Arab states but also from the European Union or from UN organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Its Human Development Index (HDI), though rising over the years, is lower (0.648) in view of Syria’s GDP. In this respect, Syria ranks 116 out of 186. When compared to other countries in the region, it ranks below Egypt, leaving only Morocco, Iraq, and Yemen at the bottom.

For decades, Syria’s international economic policy was subordinate to its foreign policy. Until the outbreak of the Syrian conflict, it was however slowly coming out of its isolation vis-à-vis the West.

In 2003, Syria signed an agreement with the EU, one of the last Mediterranean countries to do so. In 2010, negotiations started to join the World Trade Organization.

Basic Figures

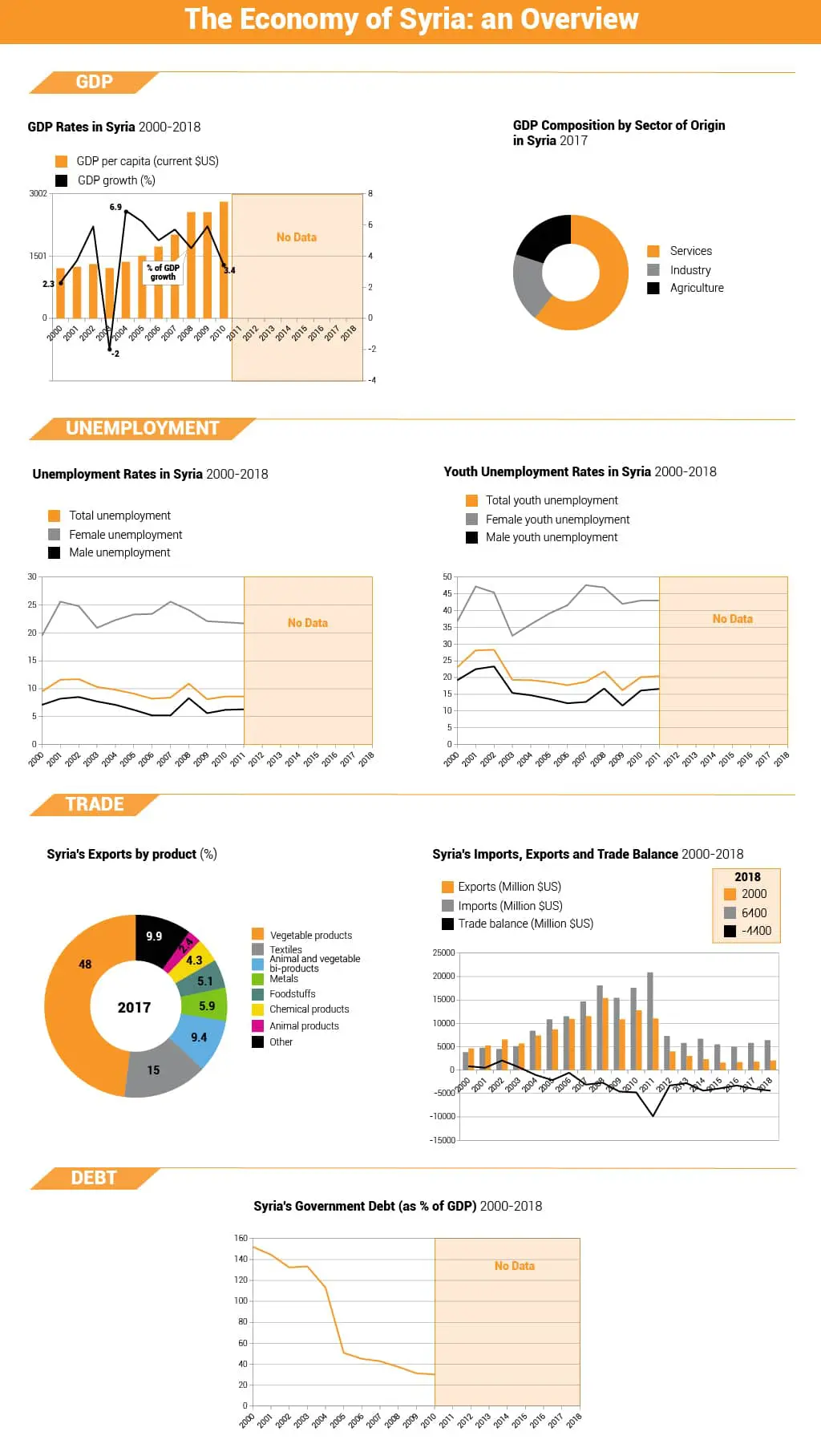

Syria’s GDP was 57.2 billion USD in 2010, 45.8 in 2011 and 32.9 in 2012 (MEED estimate). The GDP growth (annual percentage) was 3.2 in 2010, and 5.0 in 2010 (projection). According to MEED, GDP growth was -6 in 2011 and -14 in 2012 (estimate). GDP per capita was 2,892 USD in 2010 (Atlas method) and USD 4,350. Agriculture contributes 23 percent to the GDP, industry 30 percent, services 46 percent (2009).

Workers’ remittances and compensation of employees numbered USD 850 million. Foreign Aid in 2007, Official Development Assistance (ODA) and official aid was 113 million USD (against 1,698 million in 1980) in 2011; the three main donors were the European Commission (36.55 million), France (22.2 million), and Italy (3 million). Total aid is 0.1 percent of GDP. Grants, excluding technical cooperation, amounted to USD 332 million (World Bank 2011).

The ongoing conflict in Syria has had a major impact on the economy. Unemployment is thought to be as high 60 per cent (around 3.5 million people), and those living in absolute poverty was 83 per cent in 2014, up from 12.4 per cent in 2007. Most Syrians are unable to meet their basic needs. According to the World Bank, the main reasons for poverty in Syria are the loss of property and employment, the inability to access public services, including health care and clean drinking water, and rising food prices.

The conflict has damaged or destroyed large numbers of public and private facilities, including hospitals, schools, water and sewage systems, agriculture, transportation, housing and infrastructure. The World Bank put the total damage in the cities of Aleppo, Daraa, Homs, Hama, Idlib and Latakia at between $5.9 and $7.2 billion dollars in March 2016. Total infrastructure damage is around $75 billion dollars, according to the Syrian Center for Policy Research.

The United Nations estimates that investments of between $150-200 billion dollars are needed to return gross domestic product (GDP) to pre-conflict levels. The value of the Syrian lira has declined since the war broke out in March 2011, dropping from 47 Syrian pounds to the dollar in 2010, to 517 Syrian pounds to the dollar in August 2016.

Inflation in 2016 was 25 per cent, as a result of the declining exchange rate and restricted commercial movement. According to the World Bank, the prospects for the macroeconomy in the medium term are dependent on containing the war and finding a political solution, and the reconstruction of the infrastructure and social capital. Research carried out by the Syrian Center for Policy Research shows that cumulative economic losses since the start of the war amounted to 229 per cent of GDP in 2010.

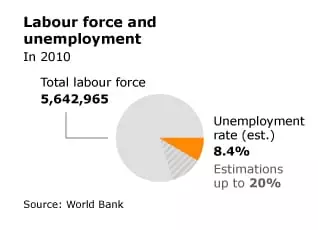

Labour force

The labour force was 5,642,965 in 2011. The unemployment rate in 2010 was estimated at 8.4 percent (World Bank). However, in the absence of accurate figures, it may be much higher, even closer to 20 percent, according to Western sources.

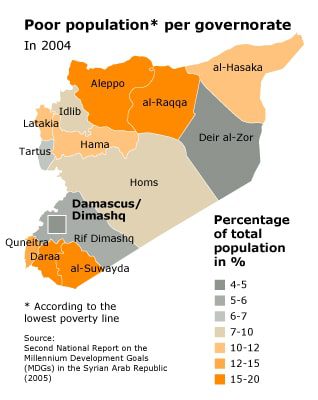

In 2007, 30 percent of the Syrian population still lived in poverty and 12.3 lived below the subsistence level. Although Syria is trying to bring down the proportion of people below the poverty line of 1.25 USD, this number is no longer an appropriate measure for extreme poverty (see the UNDP Third National Report on the Millennium Development Goals, 2010).

Inflation

The impact of the global financial crisis on Syria has been relatively moderate and mostly indirect, through linkages to trading partners in the region and Europe. Non-oil growth was estimated to have declined by 1.5 percentage points in 2009 to 4.5 percent (IMF Country Report 10/86, March 2010).

The inflation rate (consumer prices) was 2.5 percent in 2009 it increased to 4.75 percent in 2011. As a result of the continuing conflict, inflation soared to 33 percent in May 2012, according to MEED. The industrial production growth rate was 2.5 percent in 2007; investment (gross fixed) 21.5 percent of GDP (2007 estimate).

Budget

The total government revenues (excluding grants) was 21.8 percent of GDP in 2010 (International Monetary Fund, World Economic Database). The total government debt was 29.4 percent of GDP, total gross external debt is 10.4 percent of GDP (2009).

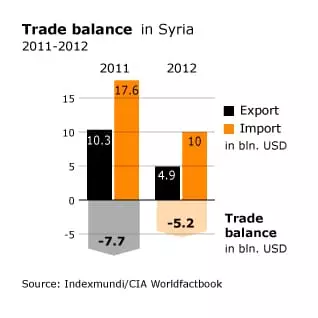

Exports of goods and services was 35 percent of GDP (2010); or USD 20.9 billion in 2010. Gross official reserves were USD 20.6 billion.

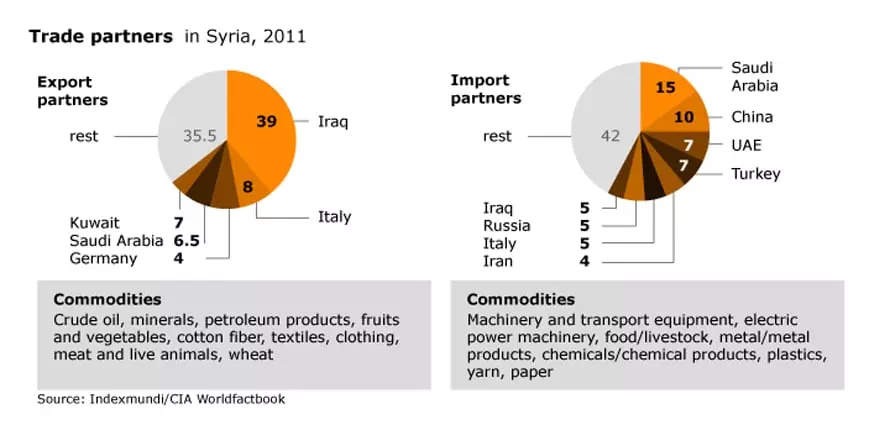

Syria exports mainly fuels (crude oil, petroleum products), iron ores and metals, and some agricultural products (fruits and vegetables, cotton fibre, clothing, meat and live animals, wheat), but their value is small (see table: Structure of merchandise exports).

Imports were 35.8 percent of GDP in 2010; import value index was: 492.8 in 2011 (2000=100):, worth USD 26.3 billion. Syria imports mainly machinery, transport equipment, and chemicals (EUROSTAT (Comext, Statistical regime 4) DG TRADE, 22 September 2009).

Current account balance: USD -1.72 billion or -2.87 percent of GDP; Average MENA 1.8 percent of GDP (2009), 5.2 percent of GDP (2010, projection) (World Economic Outlook Database 2013).

Syria’s fiscal balance has been negative for years. Due to the 2008 credit crisis, it was down to as much as -5.5 percent of GDP in 2009 (IMF Middle East Outlook 2010). However, due to the continuing violence in Syria and the fast-eroding economy, the fiscal balance turned out worse than ever. While tax revenues have been falling, the government’s spending levels remained high, which

resulted in a widening fiscal deficit of around 14 percent of GDP, according to MEED.

Economic Downturn

Since the start of the uprising in the Spring of 2011, Syria’s already weak state-run economy has been severely affected by the slowing down of economic activity, large-scale destruction, as well as by the effects of international sanctions.

Unsafe trade routes and a lack of liquidity, as a direct result of the violence, have severely harmed trade with neighbouring countries. However, informal cross-border trade and smuggling have continued. There is no economic activity along the border area with Turkey.

Tourism, 10 percent of GDP in 2010, took a nosedive: within a year average hotel occupancy in Damascus had declined from 90 to about 15 percent. While the sector experienced steady growth until 2010 (with 8.5 million visitors in 2010, a 40.3 percent increase compared to 2009), the number of tourists decreased in 2011, with 5 million visitors in 2011 (a fall of 40.7 percent compared to 2010) and 2.9 million in 2012 (UN World Tourism Organization, World Travel & Tourism Council). While travel and tourism directly generated almost 8 percent of total employment in 2010, the figure for 2012 reveals a worrying trend: the sector only covered 4 percent of employment. Around 190,000 jobs were lost over the course of two years (the sector accounted for about 200,000 jobs in 2012, compared to 390,000 jobs in 2010) (World Travel & Tourism Council).

According to IRIN, unemployment in general almost doubled from 9 percent in 2010 to 15 percent in 2011. The situation has only worsened since then. Rural areas and centres of protest such as Homs and Idleb have been particularly hard hit. Businesses in the private sector have closed down or have drastically lowered employees’ wages.

Official sources put the number of workers who have lost their jobs since the uprising began, at 90,000. Other sources estimate the number to be around three million. The already low purchasing power of the average Syrian has further decreased due to rising living costs and devaluation of the Syrian pound. Inflation stood at 30 percent as of June 2012.

Sanctions

The options for the Assad-regime to face this dramatic economic downturn are limited. Due to the opening of the Syrian market to the world market over the last decade, the economy has become more vulnerable to international pressure, such as the sanctions imposed by the European Union, the United States and the Arab League. Since oil exports are a major source of foreign currency and since more than 90 percent of Syria’s oil exports went to the EU, the Syrian government was severely hit by the EU ban on oil import. Between September 2011 and June 2012 it lost around USD 4 billion in income. Furthermore, the sanctions imposed prohibit transactions with state-owned as well as private companies. The same applies to transactions with the Central Bank of Syria. Government assets in foreign banks have been frozen. Investments by foreign governments (like Qatar) in large projects have been terminated. These projects now depend on the limited Central Bank reserves. However, the severe foreign currency crisis has hampered the ability of the Central Bank to step in. Syrian banks in general have become isolated since foreign money is no longer accessible. Because of the sanctions, Syria has had to import fuel from other countries due to limited refinery capacities, resulting in fuel shortages and increased energy costs.

As a result of all of this the government’s deficit has risen sharply. Plans to gradually remove government subsidies on items such as petrol and electricity, announced before the uprising began in a bid to ease pressure on government finances, have been reversed. For political reasons public sector wages have been raised. To tackle a growing cash problem, new money has been printed in Russia.

For the government external support has become essential to prevent a collapse of the economy. Sanctions have pushed Damascus to strengthen trade ties with Russia, importing wheat, machinery and other goods that it used to buy from Western countries. Damascus increasingly depends on a small number of countries to absorb its exports and find funding. Between March 2011 and March 2012, Iraq has increased its imports by 40 percent and Iran increased imports by 100 percent. Russia has provided Syria supplies for the industry sector and steady shipments of diesel fuel. Syria has furthermore found financial support from Russia to complete major infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure

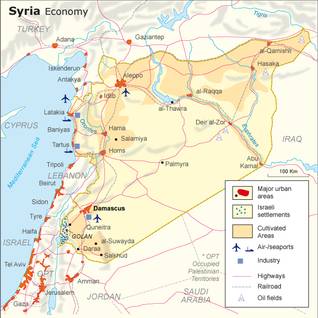

Syria is one of four countries on the Mediterranean Sea to hold oil and gas reserves (which total 8,200 Mt and 8,900 Gm3 respectively). Syria’s reserves are smaller than those of the other three countries: 400 Mt oil and 300 Gm3 gas. It has a well-developed infrastructure, as do Libya, Algeria and Egypt, for the production of oil and gas and the export of hydrocarbons, mainly to Europe (State of the Environment and Development in the Mediterranean 2009, UNEP/MAP).

Syria also has a well-developed road network, with a total of 69,873 kilometres, of which 90.3 percent is paved (World Bank 2010). It also has a railroad network, with some 1,771 kilometres of railroads, linking the main Syrian cities (State of the Environment and Development in the Mediterranean 2009). Railway lines to Tehran and Amman, however, have been suspended indefinitely.

There are three seaports on the Mediterranean Sea: Banyas, Tartus, and Latakia. Goods are also transferred via the seaports of Aqaba in Jordan, Beirut, and Tripoli in Lebanon, and Iskenderun in Turkey. 3,161 kilometres of gas pipelines and 1,997 kilometres of oil pipelines run across Syria (2010, CIA). World Aerodata lists 23 airports, 14 of which are for military use only; six are used both by military and civil air traffic (Aleppo, Damascus, Deir al-Zor, Latakia, Palmyra, and Tabaqa), and three are operated by the civil government. All civil airports have paved runways. Aleppo, Damascus, and Latakia are international airports.

In the 2012 Logistics Performance Index, Syria ranked 92 out of 155, with a score of 2.6 (down from 2.74 or 80 out of 155 in 2010). This is slightly higher than the average score for the Middle East & North Africa region (2.58) and the average score for lower middle income countries (2.55). As regards the ICT development, Internet users are a rapidly growing group, yet in 2012 they are only 17.722.5 percent of the total population (as compared to 1.45 percent in 2001), according to Internet World Statistics.

Position in the Global Market

According to the Index of Economic Freedom, Syria ranked 118 out of 179 in 2012, with a score of 51.2. In Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2012, Syria ranks 144 out of 176.

Syria’s main trade partner is the European Union (20.2 percent), followed by Iraq (17.2 percent), Saudi Arabia (11.7 percent), China (6.5 percent), United Arab Emirates (5.9 percent) and Turkey (5 percent). Its main exports partners are Iraq (38.9 percent), the EU (26.3 percent), Saudi Arabia (6.5 percent), Kuwait (4.2 percent), United Arab Emirates (3.7 percent), Libya (2.8 percent) and the United States (2.3 percent). Lebanon (9.9 percent), Egypt (5.5 percent) and France 4.9 percent. (2011) Syria’s main imports partners are the EU (16.6 percent), Saudi Arabia (14.8 percent), China (10.3 percent), United Arab Emirates (7.3 percent), Turkey (6.8 percent), Iran 5.3 percent, Russia (4.5 percent) and Iraq (4.4 percent) (2011) (EUROSTAT 2013). Syria’s trade with the biggest regional economy, that of its northern neighbour Turkey, had been growing. Turkey as a trade partner ranked sixth overall in 2011, fifth as import partner, but only eleventh as export partner.

State and Private Sectors

Syria’s economy is essentially state-run, although parts have always remained private – such as retail trade businesses. Bashar al-Assad, who became President in 2000, started to privatize more sectors of the economy.

Nowadays, the private sector provides a larger part of the GDP (about two-thirds) and employs a larger part of the workforce than the state sector. The productivity of the state sector is much lower than that of the private sector. In 2009, new reforms were implemented to open up the financial sector; until 2009, foreign investors were not allowed to own more than 49 percent of a business’ capital. However, the state still handles foreign exchange.

The country opened up to private banks in the early 2000s, the first one opening its doors in 2004. In 2005, there were six privately owned banks, in 2010, fourteen ones as well as six state-owned ones. Insurance companies remained largely state controlled until September 2009, when the first Syrian Islamic Insurance Company, a Syrian-Qatari joint venture, opened its doors – as did the heavy industry (in particular the fuel sector) and most electricity plants and the railways.

Energy

For an in-depth overview of Syria’s energy sector click on the button below.

Trade, Banking and Services Sector

Services made up 46.5 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2009 (World Bank).Trade businesses are mostly privately owned (at least the retail trade), while the financial sector, until 2000, was run by the state. At that time, the banking system in Syria consisted of the Central Bank of Syria and six state-owned banks. Reforms aimed at opening up the financial sector led to the opening of a first private bank in 2004. In 2010, the number of private banks has risen to fourteen, including three Islamic banks and ten branches of Lebanese and Jordan banks. A vast programme of modernization of the banks – including the establishment, in 2005, of a Bank Training Centre – was financed by the European Union (source: Euromed/Eurojar).

The private banks’ total deposits have grown by about 12-16 percent annually since 2006. The establishment of private insurance companies – including an Islamic insurance company – was the next step.

Total foreign assets of the Central Bank and domestic banking system rose to about USD 20 billion in 2006, and the government strengthened the private sector foreign exchange rate by about 7 percent

Overall, banking intermediation has increased substantially, although it still remains low by regional standards. Despite the achievements made thus far, considerable challenges remain, including establishing indirect monetary instruments, reducing the role of the government in credit allocation, and removing the large excess liquidity in the banking system.

The impact of the global crisis on the financial sector has been limited due to the low degree of its global exposure and CBS’s prudential requirements. The Syrian pound appreciated by about 7 percent against the dollar in 2008 in nominal terms. This contributed, along with the high domestic inflation that year, to a real effective appreciation of about 14 percent. About half of that real appreciation was reversed during 2009 with the substantial depreciation of the dollar against the Euro and the decline in Syria’s domestic inflation. Econometric estimates, which suffer from serious data shortcomings, suggest that the real exchange rate of the pound may be moderately overvalued relative to its medium-term equilibrium level. The authorities have stressed that the exchange rate reflects market forces and that it is competitive as evidenced by the rapid growth of exports prior to the global recession of 2009 (source: IMF Country Report 2010/86).

Agriculture

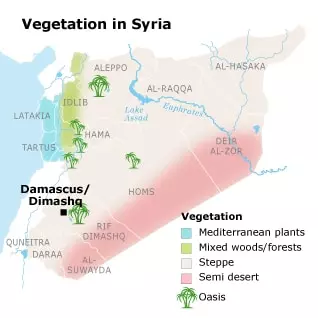

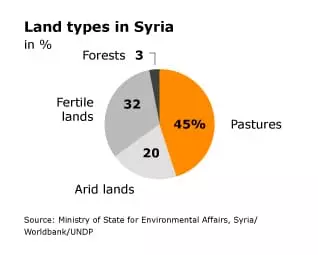

Agriculture is a relative important part of Syria’s economy, accounting for 22.9 percent of the GDP in 2009. About three quarters of the total land area is agricultural land, most of which is used as pastures. About 25 percent of the total land area is arable land, but large areas lie waste because of lack of water. In most cases, irrigation is necessary, as most of the rain falls outside the growing season.

Agricultural land extends over an area of 13,864 hectares, of which 10 percent is irrigated land, 67 percent is rain-fed land and 11 percent is fallow land (FAO-MAAR, 2001). Irrigated lands mostly concentrate along the Euphrates River, in the coastal areas and in the central regions. The size of the irrigated holdings is substantially smaller than the size of the rain-fed holdings and varies distinctively across governorates. At the national level, the average holding size is 9.2 hectare, whereas for irrigated farms it is 3.6 hectare.

The irrigated area, however small, has been increasing steadily over the last decades, almost doubling since 1985. As it is, the agricultural sector in Syria uses up to 85 percent of all the available water resources in the country. Total expenditures for irrigated agriculture accounted for almost 70 percent of all expenditures in agriculture. Yet severe droughts remain a recurrent problem (Food and Agriculture Organization, Syrian Agriculture at the Crossroads, 2003).

Pastures form 45 percent of the land. This percentage includes the Syrian Desert, providing there is sufficient rainfall (SNEAP report).

Extensive cattle breeding is mostly practiced. Syria’s top agricultural products are (in decreasing order as to value and volume) olives wheat, indigenous sheep meat, cow’s milk, tomatoes, almonds, sheep milk, anise and similar herbs, chicken meat, cotton lint, grapes, pistachios, cattle meat, cottonseed, hen’s eggs, oranges, apples, potatoes, and citrus fruits (source: FAOSTAT).

Syria’s exports of agricultural products equalled a total of USD 1.9 billion in 2010. Among its main export agricultural products are olive oil, tomatoes, anise and similar spices, wheat, and cotton products. Yet Syria is also an importer of wheat, flour and milk, among other agricultural products. Fisheries are little developed, and boats are small or medium-sized. Captured fish include sardines, tuna fish, groupers, and red and grey mullet, for a total of 18,000 tonnes in 2007 (source: FAO Statistical Yearbook).

Since 2007, Syria has been suffering from drought and harvests have failed. The World Food Program considers the north-eastern part of Syria as extremely vulnerable.

Unless stated otherwise, these data are from the World Bank or the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization.

Tourism

Tourism is an underdeveloped sector in Syria, although it was, until the recent conflict, fast growing. Many potential tourist attractions – historic or archaeological sites and museums – lack maintenance or the necessary facilities (such as transport or professional guides) to attract tourists. The continuing violence has severely affected the tourism sector in Syria. While the sector experienced steady growth until 2010 (with 8.5 million visitors in 2010, a 40.3 percent increase compared to 2009), the number of tourists decreased in 2011, with 5 million visitors in 2011 (a fall of 40.7 percent compared to 2010) and 2.9 million in 2012 (UN World Tourism Organization, World Travel & Tourism Council).

While travel and tourism directly generated almost 8 percent of total employment in 2010, the figure for 2012 reveals a worrying trend: the sector only covered 4 percent of employment. Around 190,000 jobs were lost over the course of two years (the sector accounted for about 200,000 jobs in 2012, compared to 390,000 jobs in 2010) (World Travel & Tourism Council).

Shiite Holy Places

There are three holy Shiite shrines in and around Damascus. Firstly, there is the shrine of Imam Husayn – son of Imam Ali and grandson of the Prophet – in the Umayyad Mosque. Close to the Umayyad Mosque is the mausoleum of Imam Husayn’s daughter Ruqayya. In 1985, the Iranians built a mosque on this second holy spot, the Sayyida Ruqayya Mosque. Thirdly, about 10 kilometres south of the city centre, the Sayyida Zaynab Mosque – again, Iranian-built – hosts the shrine of Zaynab, granddaughter of the Prophet and sister of Hasan and Husayn. Every day, busloads of Iranian tourists arrive in Damascus to visit these places. Most of them stay in their own hotels, financing their trip by selling Iranian products in Syria and Syrian products back home.

Informal Sector

The informal economy, or ‘extra-legal’ sector as some prefer to call it, is omnipresent in Syria. In popular perception, the informal economy is associated with street vendors and micro-businesses but, in fact, it is all-pervasive. ‘In Syria, when you think about the informal economy you need to think about supply chains, levels of employee registration – and the subsequent social benefits that go with it – and legal tenure of property and businesses,’ writes Syria Today in a special issue on poverty (Issue 61, May 2010). The magazine quotes Amer Husni Lutfi, director of the State Planning Commission, as saying: ‘Estimates vary greatly on the size of this sector, but the practical truth recognises that it is an important part of the national economy which is not counted in the GDP or the government’s plans.’ In September 2008, at the launch of the National Programme for the Informal Sector, Professor Hernando de Soto, Nobel Prize winner for Economics, who was to head this programme, estimated the informal sector at 40 percent of the economy (source Syrian Enterprise and Business Centre, SEBC).

Informal workers – often children – are omnipresent in Syria: as domestic workers, as street vendors or even shop assistants, in the agricultural sector, and also on building sites. ‘In Damascus, up to 50 percent of buildings have been built illegally and their owners consequently find themselves without the legal documentation needed to use property as collateral for a loan to start or expand a business,’ Syria Today wrote in May 2010. The workers in the informal sector are much more vulnerable than people employed in the public sector or by formal companies; they are denied social benefits and protection and what is more, they receive lower wages.

Since 2009, the SEBC – created with the help of the European Union – has been organizing trainings for workers of the informal sector in Damascus and Aleppo, in order to teach them business skills (see International Labour Office).

Regional Development

There are many regional disparities concerning standards of living and quality of life.

To begin with, rural regions are generally poorer than urban zones, the poorest rural governorates being located in the north (governorate of Aleppo) and north-east of the country (governorates of al-Hasaka, al-Raqqa and Deir al-Zor), close to the Turkish and Iraqi borders, and inhabited by (among others) poor Bedouins and Kurds. Of the latter, many have no legal status (see Relations between groups and Socio-economic composition).

Development programmes (literacy, women empowerment, trainings) are principally targeted at these regions.

Workforce and Labour Migration

The labour force represents about a fourth of the Syrian population (20.8 million in 2011, World Bank) and less than half of the working age population (44.5 percent in 2011). About 55 percent of the employed populations are wage earners, followed by self-employed (about 25 percent of the employed population). The percentage of unpaid workers (mainly engaged in family work) is significant, whilst employers constitute the smallest proportion of the working population.

Unemployment is estimated at 8.4 percent in 2011, and is much higher among the younger generations. The labour force is growing at a rate of 5 percent or 200,000 people each year, due to the high birth rate. Syria is facing an increasing youth unemployment problem. Young people aged 10-24 constitute 34.2 percent of the total population of Syria, whereas youth aged 15-24 constitute 22.2 percent. In 2011, youth employment was 19.2 percent, according to the World Bank. High population growth combined with slow increase in employment opportunities produce rapidly diminishing prospects for the growing number of young entrants.

As the State Planning Commission put it: ‘Newcomers to the Labor Market were 196 thousands. Opportunities were made for 140 thousands.’

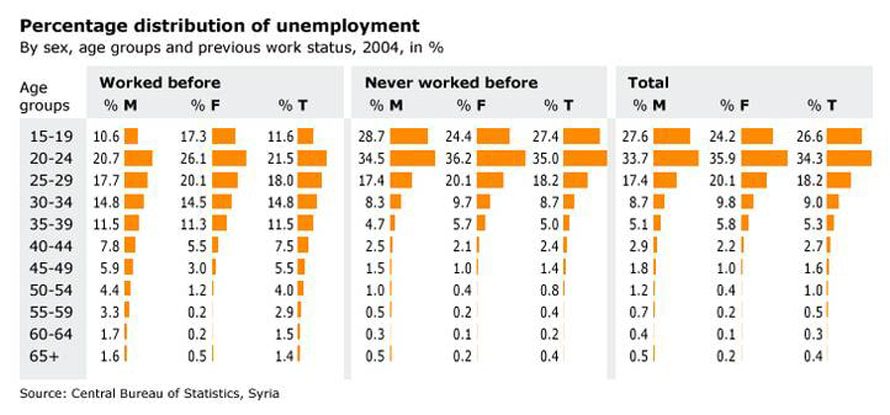

There is an important gender dimension to the unemployment in Syria. Female unemployment is estimated at 22.5 percent (2010). Unemployment rates among young women are almost twice as high as those among young men. In addition, 50 percent of young women in Syria (aged 15-29) are neither part of the labour force nor in school, suggesting potential barriers to labour market entry (see Table below).

Despite many official efforts over the years, women still lag behind in matters related to education, health, employment, political participation, and access to resources.

Workers’ vulnerability is an important issue. The structure of the Syrian labour market and the large number of jobs in the informal economy leaves the majority of workers without basic forms of social protection, and the majority of these are women, who are often exposed to financial, economic, and social risks and vulnerability resulting from their need to find employment and generate income.

The number of migrant workers increased following the adoption of the law for the employment of migrant domestic workers in 2006, which allowed Syrians to employ foreign domestic workers. They have very little protection under Syrian law, however, as their employment, although legal, is not regulated (source: International Labour Organization, Decent Work Country Programme, February 2008).

Unless otherwise stated, these data were provided by the International Labour Organization.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Economy’ and ‘Syria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: