Dana Hourany

The premiere of Disney’s latest animated feature “Lightyear” was eagerly awaited by “Toy-Story” lovers all around the world.

Fans in the MENA region, however, were disappointed.

The film was banned from theatres in Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates due to a scene involving a kiss between two female characters.

Similarly, Lebanon’s General Security banned the latest Minions film, “The Rise of Gru,” from theaters, with no official justification provided.

Theories circulating online speculated the ban to be related to a “villainous nun” character who uses nun chucks as a weapon, or an embrace between two men in the background.

“The vast majority of people across the Middle East believe that scenes involving LGBTQ+ characters indoctrinate children into switching sexualities,” Yasmin El-Jurdi, freelance Lebanese producer, told Fanack. “This sets a dangerous precedent to how the LGBTQ+ community is perceived, which is why films depicting the reality of the LGBTQ+ community are crucial now more than ever.”

Queerness in Egyptian cinema

Fear of “the gay agenda,” is an international homophobic belief, deployed by religious conservative groups that accuse the LGBTQ+ community of “strategizing to recruit children” into their “deviant lifestyle” or to “convert” them from the heteronormative path.

According to film experts, gay visibility in MENA films has long been entrenched – albeit discreetly – and continues to play a major role in embracing the marginalized LGBTQ+ population.

Long before gay film festivals became popular, Middle Eastern LGBTQ+s could find consolation and sympathetic storytelling in historic Egyptian cinema, according to Abdellah Taia, a queer Moroccan writer and filmmaker.

“Egyptian movies saved me as a queer Arab growing up with little support and encouragement from my environment,” Taïa told Fanack.

Taia and other academics praise famed Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine for his “anti-patriarchal gaze” and not-so-subtle hints at queerness in 1950s Egypt.

Jaylan Saleh, a writer and critic, claims in an essay on the subject that Chahine’s filmography objectifies men and women equally, rejecting the common male gaze that focuses only on female characters as objects of desire.

“Chahine attempted to provide a platform for Arab LGBTQ+s to be seen and heard, but he was primarily remembered as a heterosexual filmmaker with no direct ties to the LGBTQ+ community,” Taïa said.

Cinema as a solace

Taia came out as gay to a Moroccan magazine in 2007. This led to fierce backlash and familial pressures. Settling in Paris after having moved there provided some relief albeit momentarily.

The author credits classic Egyptian film with easing his traumatic upbringing as a lone homosexual person in a difficult environment.

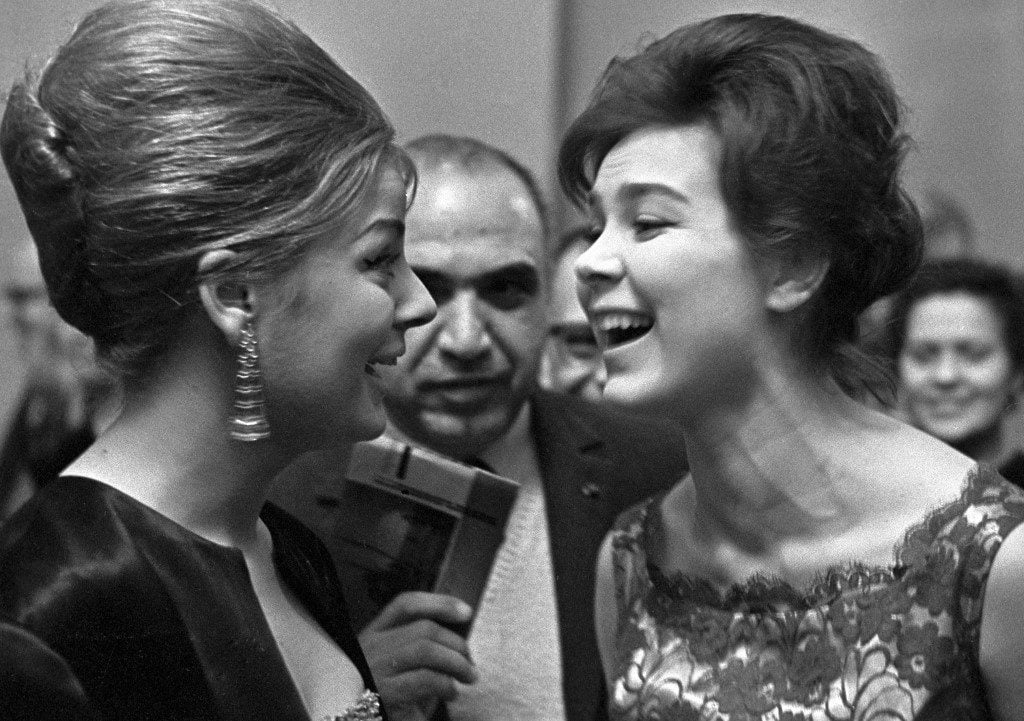

Egyptian golden-era stars such as Soad Hosny, Nadia Lutfi, Faten Hamama, and Hend Rostom played roles to whom young Arab LGBTQ+s could relate, he said.

“Egyptian cinema is profoundly queer, not because of its blatant representation of homosexuality, but because of its capacity to draw out the realities of oppressed communities that face intersectional prejudice,” the filmmaker added.

Films depicting poverty, physical assault, gender discrimination, power conflicts, and persecution communicated to Arab LGBTQ+s that their anguish was shared and understood, according to Taia.

“The rumored bisexuality of Arab icon and singer Umm Kulthum, coupled with the unconventional sensitivity of famous Arab singer and actor Abdel Halim Hafez, defied entrenched gender norms and validated the existence of non-heteronormative individuals throughout modern Arab history.”

Modern progress

In the recent decade, more direct attempts have been made to promote LGBTQ+ themes in Arab cinema.

In her 2007 film “Caramel,” Lebanese filmmaker Nadine Labaki, for example, hinted at the presence of a lesbian character. “Rima” is a non-stereotypical woman who is uninterested in men and has one flirtatious moment with another woman that is only expressed discreetly through their body language.

A more recent example is Netflix’s first Arabic Original Film, “Perfect Strangers,” which features one homosexual character whose sexuality is addressed albeit in a limited manner in the storyline.

The film sparked outrage in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), with opponents accusing Netflix of condoning homosexuality and “moral degradation,” as well as “inserting Western notions into an otherwise conservative society.”

Much of the rage was directed at Egyptian actress Mona Zaki, who removed her underwear in one scene despite the fact that no nudity was displayed.

El-Jurdi sees hints towards homosexuality as a crucial step in laying the groundwork for more developed LGBTQ+ plots.

“You can’t parachute these storylines onto mainstream audiences, they might immediately reject them. At least we’ve reached a point where we can introduce characters that aren’t straight. We can now work toward the next step,” El-Jurdi said.

Filmmakers wishing to illustrate LGBTQ+ topics in the MENA region are faced with a myriad challenges. Since homosexuality is either illegal or punishable by law in many countries, filmmakers are met with financial, social, and legal limitations, El-Jurdi explains.

Overcoming one obstacle after another

To curb state censorship, Arab filmmakers are compelled to show their films abroad. While the West offers the majority of opportunities, film festivals such as “Cinema Al Fouad” in Lebanon and “Mawjoudin Queer Film Festival” in Tunisia challenge the oppressive status quo and create more safe spaces for LGBTQ+ art.

“While Lebanon enjoys broader liberties than other traditional Arab countries, if security officers detect gay sequences in a film, they can shut it down and restrict public viewing. There are several measures that must be taken,” El-Jurdi said.

The producer notes that one of the most difficult obstacles to overcome is obtaining funding for LGBTQ+ films.

“Regional production businesses see LGBTQ+ storylines as harmful to their PR, and Western investors may insist on having a local production company on board for feature film productions,” she says.

Furthermore, the Lebanese government’s recent crackdown on LGBTQ+ gatherings, including film screenings, threatens the margin of freedom earned and fought for by the country’s LGBTQ+s.

A never-ending fight

The obstacles placed before LGBTQ+ projects did not deter El-Jurdi from her profession; rather, they spurred her into battle.

“Western films can’t depict Arab LGBTQ+s the way we can. It’s our job to combat queer stereotypes and one-dimensional depictions of the community. These are humanizing stories that could potentially alter the minds of homophobes,” the producer said.

Similarly, Taïa believes that worldwide LGBTQ+ productions have omitted much-needed narratives that delve into the intricacies of queer realities.

Furthermore, El-Jurdi claims that queer filmmakers from Egyptian and Lebanese origins dominate the scene, while Gulf and war-torn MENA countries have a shier presence.

“It’s crucial to have stories from all over the region so that everyone’s voice is heard and every experience has a chance to express itself,” the producer said.