In the final days of 2017, rising prices and ongoing economic problems in Iran sparked a widespread national protest that shocked the political establishment. Although most of the protesters chanted anti-establishment slogans, the dire economic situation was the main cause of the unrest. The uprising has largely dwindled, but the main cause of the uprising has not gone away. As all eyes are focused on President Hassan Rouhani for a swift economic solution, how realistic are his chances of providing a remedy for the country’s economic woes?

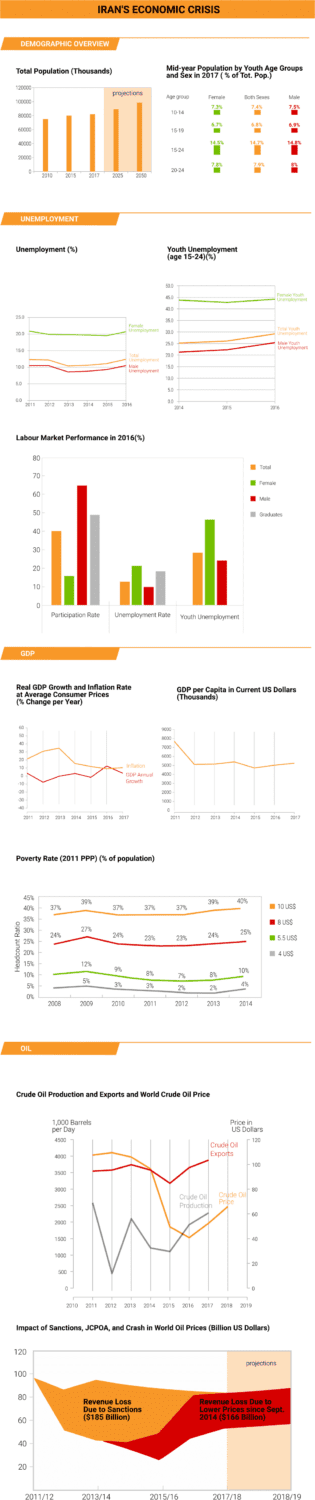

Rouhani inherited a devastated economy from President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2013. Despite high oil prices during Ahmadinejad’s tenure, the economy has been paralyzed by years of international sanctions, endemic corruption, hyperinflation and mismanagement. Since Rouhani’s election in 2013, annual inflation has fallen from 34 per cent to 10 per cent.

Furthermore, growth has returned, with organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projecting that the economy – which was contracting five years ago – will expand by 4.2 per cent in the three months to March 2018. Yet although these figures inspire confidence on paper, their impact has not been felt across the country.

One of the main challenges facing Rouhani is unemployment. Officially, the unemployment rate is around 12.5 per cent. However, the rate among those aged 15 to 29 is well over 24 per cent and is even higher among urban youth and women. The IMF has called Iranian women an ‘untapped source of growth and productivity’.

Youth unemployment is a multidimensional problem, one of which is brain drain, which is costing the country over $150 billion per year. On average, about 150,000 educated Iranians leave the country every year, which has both short-term and long-term consequences for the economy.

Iran’s currency, the rial, was under intense pressure in 2017, dropping to 42,900 against the dollar from 36,000 at the end of 2016. Rouhani could support the currency by spending more of Iran’s foreign reserves, but this could jeopardize foreign investment, which is already under pressure from new sanctions threatened by the United States. Attracting foreign investment has already been difficult for the government. Following the nuclear agreement in 2015, Rouhani said that his country aims to attract at least $30 billion a year of foreign investment.

Foreign direct investment in 2016 was just over $3.4 billion, a 64 per cent increase compared with 2015 but significantly lower than the amount Iran needs to achieve its economic objectives.

In December 2017, the government proposed a budget to parliament for the Iranian year starting on 21 March 2018. The $104 billion budget was up about 6 per cent from the previous year but a decrease in real terms at current inflation rates. In the budget, the government proposed slashing subsidies on basic goods, including food, and services for the poor as well as raising fuel prices by as much as 50 per cent. Religious institutions, over which the government has little authority, are spared the austerity.

This disparity underlines one of the main challenges facing the Iranian economy: powerful economic interest groups are not accountable to the government. These interests, which according to some estimates control over 60 per cent of assets in Iran, generally to not pay tax and stifle competition from small private companies, restricting job creation.

Three main sectors make the Iranian economy: public, private and semi-state. The semi-state sector includes revolutionary, military and religious foundations and cooperatives, and social security and pension funds. As a result of flawed privatization processes in recent decades, the ownership of many state enterprises and businesses has been shifted to the semi-state sector. Therefore, the semi-state sector has gradually become the economy’s largest constituency. When a major segment of the economy is not accountable to the government and does not sufficiently contribute to the state coffers, there is a limit to the economic improvements the government can make.

Furthermore, corruption is endemic. In 2016, Transparency International, a global civil society organization, ranked Iran 131 out of 176, making it one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Both the government and other public bodies acknowledge the problem but have been unable to agree on how to tackle it.

So, what are Rouhani’s options? He won a landslide election victory on his promise to transform the situation, but he lacks the necessary power to make any radical changes. It is hardly surprising then that many people who voted for him now regret their choice.

This sense of disillusionment not only affects the government but could have serious consequences for the rest of the regime. Despite their differences, when it comes to regime survival, both the reformists and the hardliners have a lot in common. Indeed, all factions were shaken by the scale of the recent uprisings, and they know that popular anger is growing even though order has been restored.

A radical economic transformation requires serious compromise from every segment of the establishment – a compromise that those currently benefitting from the corrupt system are unlikely to make. What is certain is that the status quo, which has left many Iranians desperate, will pave the way for periodic outbreaks of dissent that could get out of control at any time.