Introduction

Iran is an Islamic Republic, combining elements of an Islamic theocracy with democracy. The highest power lies with the Supreme Leader (Rahbar) of the Islamic Revolution, currently Ayatollah Sayyed Ali Khamenei. Iran’s human rights record is poor, and freedom of the press severely curtailed. Civil society is developed but is under great pressure from the government. Although foreign relations have improved since the late 1990s, tensions between Iran and the West – especially the United States – and Israel remain great.

Iran’s complex political system is, in many ways, an experiment, combining elements of a modern Islamic theocracy with democracy. According to the Constitution, the Islamic Republic of Iran is a republic with separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Ultimate political authority is vested in a learned religious scholar referred to commonly as the Supreme Leader, who, according to the Constitution, is accountable only to the Assembly of Leadership Experts. In practice, he is answerable to no one.

Iranians elect the President and the Parliament every four years. The Assembly of Leadership Experts is elected every eight years. Candidates for elected office (i.e., the presidency, Parliament, and the Assembly of Leadership Experts) are scrutinized by the Guardian Council, which consists of 12 jurists, including six clerics appointed by the Supreme Leader (Rahbar), and six jurists elected by the Majles (Parliament). The voting age was fifteen until January 2007, when it was raised to eighteen.

The Executive

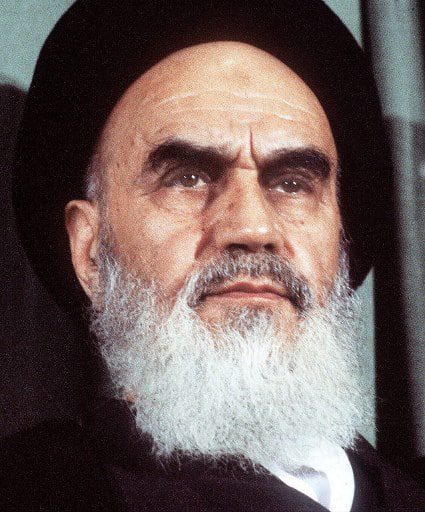

The most important figure in the Iranian political system is the Vali-ye faqih, an expert in religious law, who is referred to in the Constitution as the Supreme Leader (Rahbar) of the Islamic Revolution; he is the highest-ranking political and religious authority of the nation. Ayatollah Khomeini was the first Supreme Leader. The Assembly of Leadership Experts, an 86-member body of senior clergymen, elects the Supreme Leader by a majority vote. On 4 June 1989 Ayatollah Khomeini was succeeded by Ayatollah Khamenei, who has held that position since then.

The Supreme Leader has many executive powers. He sets general state policy and chooses the head of the judiciary and military commanders. He commands the armed forces, including the intelligence and security agencies, and can declare war and peace. He can initiate and supervise amendments to the Constitution. Directors of the national television and radio networks and heads of major religious and economic foundations are appointed by him and report directly to him.

The Assembly of Leadership

The Assembly of Leadership Experts (or Assembly of Experts) is an 88-member body of senior clergymen, who are elected by popular vote to 8-year terms. The Assembly evaluates the work of the Leader and is authorized to dismiss the Leader. The current chairman of the Assembly is Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi (since 10 March 2015).

The President

The executive branch is headed by the President, who is elected by universal suffrage for a term of four years and is limited to two consecutive terms. The President is the highest state authority, after the Supreme Leader. According to the Constitution, the President must be an Iranian national and a Shiite. Although the Constitution does not specify the sex of the President, female candidates have so far been banned from running in presidential elections. The President selects several Vice-Presidents (currently twelve) and a cabinet of 21 ministers. The ministers but not the Vice-Presidents are subject to approval by Parliament.

The President is responsible for the implementation of the Constitution and for the exercise of executive powers, except for matters under the control of the Supreme Leader. The Supreme Leader can dismiss a President if two-thirds of the Parliament votes to impeach him. The relationship between the President and the Supreme Leader is of great importance to the executive power of the President. During his tenure Rafsanjani (1989-1997) wielded considerable power, but Khatami’s power (1997-2005) was often curtailed by conservative opponents in favour of the Supreme Leader.

The Legislative

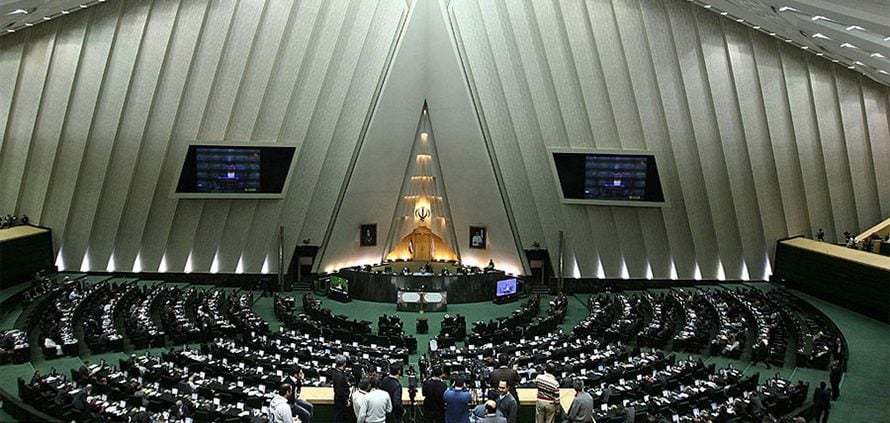

The legislative branch consists of the Parliament and the Council of Guardians. The Expediency Council was created to solve disputes between the two legislative bodies.

The Majles-e Shura-ye Eslami (Islamic Consultative Assembly), consists of 290 members, who are elected for four-year terms. The Majles approves the national budget, drafts legislation, and ratifies international treaties. All Majles candidates and all legislation from the assembly must be approved by the Guardian Council. Five seats are reserved for the representatives of the officially recognized religious minorities: two for Armenian Christians and one each for Zoroastrians, Jews, and Assyrian Christians. The Majles can propose and pass legislation and cannot be dissolved by the executive branch. Cabinet ministers can also present bills. The current speaker is Ali Larijani (since 3 May 2008).

Guardian Council

All bills passed by the Majles (Parliament) must be reviewed by the Guardian Council (in full, Council of Guardians of the Constitution) for consistency with the Constitution and Islamic principles. The council consists of twelve jurists, including six canonist clerics (experts in Islamic law) appointed by the Supreme Leader and six jurists (experts in civil law) elected by the Majles from a list of twelve nominations given to it by the head of the judiciary, who is appointed by the Supreme Leader. The council interprets the Constitution and Sharia (Islamic law) and may reject bills from Parliament. If a bill is found compatible with the Constitution and Islam, the bill is passed; if the council finds a bill partially or wholly unconstitutional or un-Islamic, the bill is sent back to the Majles for revision.

The council has been chaired by Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati since 29 August 1988.

Expediency Council

In 1988 the Expediency Council (in full, the Expediency Discernment Council of the System) was established to resolve disputes between the two legislative bodies. The Expediency Council can either uphold or override the Guardian Council vetoes, or send back vetoed legislation with instructions that the Majles and the Guardian Council work out an acceptable compromise. It also serves as an advisory body to the Supreme Leader, which makes it one of the most influential bodies in the country. After the sudden death of Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani on 8 January 2017, Ayatollah Mohammad Ali Movahedi-Kermani took over as interim head of the Expediency Council on 1 February 2017.

The Parliamentary Elections of 2012

The parliamentary elections for the Ninth Islamic Consultative Assembly (or Majlis), were held in Iran on 2 March 2012, with a second round on 4 May 2012 in those 65 districts where no candidate received at least 25 percent of the votes cast.

More than 5,000 candidates registered, but more than a third of those were disqualified by the Guardian Council, leaving about 3,400 candidates to run for the 290 seats representing the 31 provinces.

In the elections, pro-Khamenei supporters won a large majority of seats over pro-Ahmadinejad candidates. Although the Parliament has no direct control over key foreign-policy and security matters, it does have some influence over those policies and coming elections. In the wake of the crushing of the reformist protests against the 2009 election results, the Guardian Council allowed few if any reformist candidates to run. The new Parliament was opened on 27 May 2012.

The second round of elections in April 2016 saw the reformists win 129 seats while the conservatives won 83 seats. The remaining seats were distributed between the independents and minority parties.

The Judiciary

The head of the judiciary is appointed to a five-year term by the Supreme Leader. He appoints the members of the Supreme Court, the highest judicial authority, and approves the candidate list from which the President chooses a minister of justice.

The legal system is based on Sharia (Islamic law). The judges of all courts must be experts in Islamic law. There are public courts, which try conventional civil and criminal cases; revolutionary courts, for cases involving political offenses and national security; special courts, for members of the security forces and government officials; and a clerical court, which deals with crimes committed by members of the clergy, including ‘ideological offences’.

Political Parties

Formal political parties are a recent phenomenon in Iran. The Islamic Republic Party was Iran’s ruling political party – for some years its only political party – until its dissolution in 1987. It was not until 1994 that a new party, Implementers of Development, was formed, mostly by close allies of the then President Rafsanjani.

After the election of Khatami as President of Iran in 1997, more parties started to operate, and political parties were legalized in 1998. Nonetheless, coalitions based on special interests and patronage, rather than parties, still dominate Iranian politics. These coalitions – usually including political parties as well as less formal groups and organizations – are often formed before elections and disbanded soon afterwards. Only groups that accept the Constitution and the principle of velayat-e faqih are permitted to operate.

The 2nd of Khordad Movement, which was formed in 1997 and is named after the day and the month of Khatami’s election victory as President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, consisted of eighteen reformist groups that supported Khatami’s election and his policy. The coalition was successful in the 2000 parliamentary elections, but internal differences erupted over specific economic policies, and these hampered the coalition’s effectiveness.

The Alliance of Builders of Islamic Iran (Abadgaran), a new conservative group, won a majority of the seats in the 2004 parliamentary elections. Conservatives also prevailed in the 2008 parliamentary elections. Hardline conservatives, among them former President Ahmadinejad, have attempted to close ranks under the United Front of Principlists.

Many candidates belonging to the Islamic Iran Participation Front (IIPF), one of the reformist groups that formed the 2nd of Khordad Coalition, have faced disqualification since the 2008 parliamentary elections and the IIPF was banned altogether in June 2010.

After the Revolution, the new government harshly suppressed opposition groups critical of the new state. Many active members of the opposition were executed or forced to flee the country. Most opposition parties that were suppressed inside the country were reorganized abroad. More than fifty political parties are active in Iranian exile communities, including monarchists, democrats, socialists, Islamists, Marxists, and ethnic nationalists.

Armed political groups that were repressed by the government include the Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK or MKO); the People’s Fedaian (or Fedayeen); the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (usually abbreviated KDPI); and the People’s Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK).

Opposition groups

After the Revolution, the new government harshly suppressed opposition groups critical of the new state. Many active members of the opposition were executed or forced to flee the country. Most opposition parties that were suppressed inside the country were reorganized abroad. More than fifty political parties are active in Iranian exile communities, including monarchists, democrats, socialists, Islamists, Marxists, and ethnic nationalists.

Armed political groups that were repressed by the government include the Mojahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK or MKO); the People’s Fedaian (or Fedayeen); the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (usually abbreviated KDPI); and the People’s Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK).

Politicians

Grand Ayatollah Sayyed Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini

Grand Ayatollah (usually referred to as Ayatollah) Sayyed Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini (24 September 1902–3 June 1989) was the leader of the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the first Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran. He had a long history of conflict with the regime of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. In the 1960s Khomeini was repeatedly arrested for his criticism of the pro-Western regime of the Shah. In 1964 he was exiled, living in Turkey, Iraq (in Najaf), and then France, from where he continued his opposition to the Shah. His outspoken criticism, arrests, and exile elevated him to the status of national hero. On 1 February 1979 Khomeini returned from Paris to Iran in triumph. After the proclamation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Khomeini was appointed Iran’s political and religious leader for life.

Ayatollah Sayyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei

Ayatollah Sayyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei (born 15 July 1939) has been Supreme Leader of Iran since the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989. Born into a minor clerical family, he studied theology in Mashhad and in Qom with Khomeini. He was a hojatoleslam, a middle-ranking cleric, and served as President of Iran from 1981 to 1989. After Khomeini’s death, the Assembly of Leadership Experts elevated him to the rank of ayatollah and elected him the new Supreme Leader.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (born 28 October 1956) was the sixth President of Iran. He was the mayor of Tehran between June 2003 and August 2005, served as governor general of Ardabil province, and was a member of the Revolutionary Guards during the Iraq-Iran War.

He is the son of a blacksmith and grew up in poverty, a theme he often mentions. He won the June 2005 presidential elections by campaigning on populist themes: emphasizing his own modest life-style and promising to ‘put the petroleum income on people’s tables’, revive Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolutionary ideals, and root out poverty. He is the first non-clerical President in 24 years. He is regarded as a hard-line conservative politician and enjoys the support of some of the most conservative and hard-line clerics. His reappointment after the June 2009 presidential elections was marred by controversy and prompted charges of election irregularities by reformist candidates Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. Massive protests during the summer of 2009, led by reformist politicians and civil society activists and widely known as the Green Movement, were harshly suppressed.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

Hojatoleslam (later Ayatollah) Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (born 15 February 1934) has been a leader of the Islamic Republic since its inception. He is widely regarded as the most influential person after the Supreme Leader. Rafsanjani studied theology in Qom with Khomeini, becoming a fervent adherent of his ideas. During the 1960s Rafsanjani was jailed several times for dissident activities against the Shah’s regime. After the Revolution he held several high positions, including first speakership of the Majles (Parliament) (1980-1989), the presidency (two terms, 1989-1997), head of the Assembly of Leadership Experts (2007-2011), and the chairmanship of the Expediency Council (from its inception in 1989 to the present).

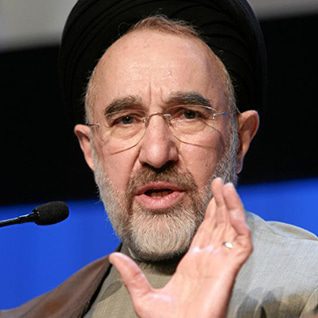

Mohammad Khatami

Ayatollah Sayyed Mohammad Khatami (born 29 September 1943) was President for two terms (1997-2005). Running on a reform agenda, Khatami won the 1997 and 2001 presidential elections with landslide victories. Before serving as President he was Minister of Culture, during which period he relaxed censorship on books and films, angering conservative forces. As President, he advocated civil society, freedom of expression, and the rule of law.

Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rouhani (born 12 November 1948) was elected president on 14 June 2013. Among his previous positions was Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council from 1989 to 2005. In the latter capacity, he was the country’s top negotiator with the EU three (the United Kingdom, France and Germany) on nuclear technology in Iran. As a defender of the reformist Green Movement, Rouhani secured more than 50 per cent of the vote to win the elections.

Corruption

In the 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Iran ranked 130th among 180 countries that were surveyed. Iran’s performance is far below the world average and holds one of the lowest ranks in the Middle East region. Only Yemen, Syria, and Iraq rank lower. Although Iran has been a signatory to the United Nations Convention against Corruption since 9 December 2003, it has not yet ratified the convention.

‘Where do all the oil dollars go?’ is a question frequently debated. Many Iranians see corruption and mismanagement as major causes of the country’s dire economic situation. In the summer of 2008 a fierce debate arose when the little-known government functionary Abbas Palizdar accused senior religious leaders and politicians of deep involvement in corruption.

He was arrested and charged by a Tehran prosecutor with ‘propagating lies’ and ‘confusing public opinion’. To many Iranians the accusations only proved what they had known already – that the establishment is corrupt at the highest levels.

While running for President, Ahmadinejad portrayed himself as an incorruptible man of the people, who would fight corruption. He has blamed Iran’s economical problems on ‘economic mafia’ and has replaced many officials accused of corruption in ministries. According to the International Crisis Group, Ahmadinejad’s policy has not resulted ]in far-reaching changes, and he himself has been guilty of political favouritism.

Bureaucracy

The bureaucracy in Iran is as complex as its government, and it is, in practice, often a maze of form-filling and stamps. Decision-making is blighted by complexity and a lack of transparency. The state controls almost all public services in Iran. Patronage and corruption of the bureaucracy are pervasive, resulting in the dissatisfaction of the public.

Changing money, buying a house, or setting up a business – everything in Iran takes a mountain of paperwork, hours of waiting in lines, and going from office to office. Bureaucrats often lack experience and training. Civil servants are generally poorly paid, and a small extra payment can usually speed up the process.

This everyday corruption is not just frustrating, it is highly discouraging for setting up businesses and attracting foreign investors.

During his presidency, Khatami pledged to tackle the problem, and some efforts were made to fight corruption and reduce bureaucracy.

President Ahmadinejad also announced reforms. On his personal blog he writes, ‘Our slogan should be: Bureaucracy at the people’s service, not the people serving bureaucracy.’ But, although some progress has been made, an oversize bureaucracy and widespread corruption remain major problems.

Foreign Relations

In the years following its establishment in 1979, the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran was dominated by a confrontational ideology. Non-alignment and the export of the Revolution were its leading concepts. ‘Neither East nor West’ was Iran’s slogan in foreign relations, as it distanced itself from both superpowers, propagating the view that it would never become an instrument in the political game of the Cold War.

Although relationships with the Soviet Union, and later Russia, improved greatly over time, relations with the United States have remained tense. Since the 1980 hostage crisis, diplomatic relations between Iran and the United States have been severed.

The Shah’s maintenance of diplomatic and commercial ties with Israel, seen as a state hostile to Muslims and Islam as a whole, was a thorn in the side of many Iranians.

During his exile Khomeini issued numerous declarations in which he attacked the State of Israel. The Islamic Republic’s policy towards Israel was therefore directed mainly at supporting the fight against the Israeli state. Not only does Iran support Hezbollah in Lebanon politically, economically, and militarily, but members of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Pasdaran) have been active there as well.

Since its establishment, the Iranian leadership has attacked the institution of the monarchy in various Persian Gulf states as an un-Islamic institution and denounced Persian Gulf rulers ‘as corrupt men who depleted the valuable oil resources of their countries to satisfy the ever-growing demands of America, the Great Satan, and who denied their subjects any role in policymaking’. Over the years, Iran’s relations with its neighbours have been improving, although Iran and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) still dispute sovereignty over three islands in the Persian Gulf – Greater and Lesser Tunb and Abu Musa.

Khatami’s tenure improved relations with Iran’s neighbours and with many Western countries, except for Israel and the United States. Stressing a ‘dialogue among civilizations’, Khatami sought to improve commercial and geopolitical relations with Western Europe and Japan. In the early 2000s, the Khatami administration also attempted to find common ground with the United States.

In 2002, however, the George Bush administration declared Iran part of the ‘Axis of Evil’. Relations deteriorated further in 2004 because US officials believed that Iran intended to develop nuclear weapons. Relations with Europe also declined because of disputes over Iran’s nuclear programme. Former President Ahmadinejad’s confrontational attitude in foreign policy has not helped to normalize international relations. But with the coming into office of Obama administration, the Iranian presidential elections in June 2009, and the need for cooperation in the region (because of the on-going crisis in Afghanistan and delicate balance of power in Iraq) hopes for direct diplomatic relations surfaced.

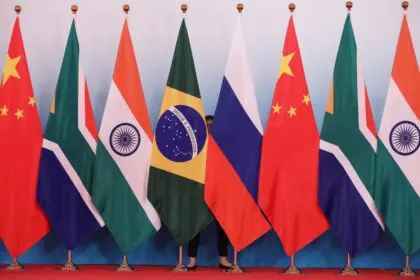

On 14 July 2015, Iran reached an agreement with six world powers (the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, France and Germany) to limit Iranian nuclear activity in return for the lifting of international economic sanctions.

Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war in March 2011, Iran has supported Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, with thousands of Iranian Revolutionary Guards deployed to fight alongside regime forces.

Political History

In 1921 Reza Khan, a military officer in Persia’s Cossack Brigade, led a coup against the government, and in 1925, by terminating the Qajar Dynasty, he declared himself Shah (king) of Persia and founded the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah set out to modernize the country. The country’s pro-Axis allegiance in World War II led to the Anglo-Russian occupation of Iran in September 1941. Reza Shah abdicated in favour of his son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, and went into exile.

In the early 1950s a struggle for control of the Iranian government developed between the Shah and Mohammad Mosaddeq, a charismatic Iranian nationalist and political leader. Iranian desire for nationalization of the oil industry had been growing since the 1940s. In April 1951 Mosaddeq secured passage of a bill in Parliament to nationalize British petroleum interests in Iran. Mosaddeq’s popularity and power grew rapidly. By the end of April the Shah was forced to appoint Mosaddeq premier.

In August 1953 he tried to dismiss Mosaddeq but was unsuccessful and, in the face of widespread opposition by Mosaddeq’s supporters, decided to leave the country. Several days later, however, Mosaddeq’s opponents, supported and funded by the British and US governments through their secret services, brought down the government (on 19 August 1953) and restored the Shah to power.

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi’s authoritarian rule and uneven Westernization programmes led to rising discontent. Massive demonstrations and strikes erupted during the late 1970s. The broad opposition forces included nationalists, leftists, and Islamists. The Shah and his family fled Iran on 16 January 1979.

On 1 February 1979 a leading opposition figure, Ayatollah Sayyed Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, returned from France, where he had been exiled for his opposition to the Shah’s regime. In his writings and preaching Khomeini developed the theory of velayat-e faqih (the guardianship of the jurisconsult), which included theocratic political rule by Islamic jurists and provided the theological basis for Khomeini’s rule of Iran.

Islamic Republic

On 1 April, under Khomeini’s leadership and following a nationwide referendum, Iran was declared a theocratic republic guided by Islamic principles and was renamed Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran (Islamic Republic of Iran). The senior figure in the system became the leading faqih (jurisconsult, legal scholar), who is referred to in the new Constitution as the Supreme Leader (Rahbar) of the Revolution. The Constitution named Ayatollah Khomeini the first faqih to lead the Islamic Republic.

A day after the death of Khomeini on 3 June 1989, the Assembly of Leadership Experts promoted the acting President, Hojatoleslam Sayyed Ali Khamenei, to the status of Grand Ayatollah and elected him the new Supreme Leader. Hojatoleslam Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, then speaker of the Majles (Parliament), was elected President.

In June 1997, a reform-minded cleric, Sayyed Mohammad Khatami, was elected President by a landslide. Pursuing political reform, liberalization, the normalization of relations with the West, and the reduction of tensions in the region, Khatami was supported by broad sectors of society. But when his promised reforms did not materialize, public disappointment and disenchantment grew. While some suggest Khatami had never really set out to reform Iran, others believe that he did not have the necessary power to do so and that he was blocked by hard-line conservative elements in the clerical establishment.

Leading up to the 2004 parliamentary elections, the hard-line twelve-member Guardian Council disqualified more than 2,500 reformist candidates, including over 80 sitting members of the 290-seat Parliament. In February 2004, conservatives won a landslide victory in parliamentary elections, a setback for Iran’s reformists. In June 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the former mayor of Tehran and a hard-line conservative, won the presidential election with 62 percent of the vote.

After the reformists’ most prominent members had been barred from running by the Guardian Council, religious conservatives secured a comfortable majority in the parliamentary elections of March 2008.

The presidential elections of June 2009 were marred by controversy: Ahmadinejad’s claim of victory with 62.6 percent of the vote was rejected by the main opposition candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi.

The country was thrown into turmoil after supporters of the presidential opposition candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi took to the streets to protest the election results and were met with harsh security crackdowns. And in June 2013, the reformist Hassan Rouhani won the presidential elections.

Armed Forces

Introduction

Restricted by years of international sanctions, Iran has been unable to source many weapons from abroad, forcing it to grow its military through a robust domestic defence industry. Iranian forces, particularly the elite al-Quds brigade of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp, have played a key role in the fighting in both Syria and Iraq. Tehran has also provided support to Houthi rebels in Yemen.

In 2019, Iran ranked 14 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 1.4 million personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $6.3 billion. In 2018, military expenditure accounted for 2.7 per cent of GDP, compared with 3.1 per cent in 2017 and 3 per cent in 2016, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Occupied during both world wars, Iran developed its military capabilities to defend itself. Part of the country’s pre-1979 military doctrine was based on the same history: to protect itself from the neighbouring Soviet Union, Iran should be backed by another superpower, the United States (US).

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 873,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 523,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 350,000 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 509 | 24 |

| Fighter aircraft | 142 | 17 |

| Attack aircraft | 165 | 18 |

| Transport aircraft | 89 | 7 |

| Total helicopter strength | 126 | 34 |

| Flight trainers | 104 | 29 |

| Combat tanks | 1,634 | 18 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 2,345 | 31 |

| Rocket projectors | 1,900 | 4 |

| Total naval assets | 398 | - |

| Frigates | 6 | - |

Iran’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

The military doctrine following 1979’s Islamic Revolution, which saw the introduction of the foreign policy motto ‘neither East nor West’, sought to establish a domestic military industry that did not rely on any of the superpowers of the time to fend off threats. The Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, which is called the ‘Imposed War’ in Iran to indicate Iraq’s aggression, added a new dimension to that military mindset: Iran cannot count on international support even if it falls victim to regional aggression. As such, a focus on further building internal military capabilities started in the late 1980s and has continued to this day. Iran’s ballistic and cruise missile programmes and its regional alliance-building mechanisms are significant parts of these efforts.

Iran’s armed forces are made up of three military institutions: the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Law Enforcement Force. These institutions operate under the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the head of which is appointed by the commander-in-chief of the armed forces who is also the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Two other important bodies with regards to the armed forces are the Ministry of Defence, which is tasked with planning and providing military equipment for the three military institutions, and the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which is responsible for coordinating the armed forces through the Khatam al-Anbia strategic headquarters in times of war.

Islamic Republic of Iran Army

The army was established before the Islamic Revolution. Although it was subsequently reshuffled and renamed (it was previously called the Royal Army), it continued functioning with almost the same tradition of military training and strategic planning and doctrine. Reza Khan, who later became Iran’s first Pahlavi shah, established the Royal Army in 1921. The Royal Army became one of the Middle East’s main military forces after the oil boom in the early 1970s under the second Pahlavi shah, who was obsessed with the Soviet threat on Iran’s northern borders and growing Soviet influence in the region. When he was forced out of the country, it was the Royal Army’s decision to embrace Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini that ended the Pahlavi era. After the revolution and the establishment of the IRGC, the army ceased to be the main military institution, a position it now shares with the IRGC.

According to Article 143 of the Iranian constitution, the army is responsible for ‘safeguarding the independence and territorial integrity of the Islamic Republic of Iran’. The army consists of four forces: the land force, air force, navy and air defence force. The head of the army, currently Seyyed Abdolrahim Mousavi, is appointed by the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

From the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s to the war against the Islamic State in the 2010s, the army has always been part of Iran’s military confrontations. There are seven military colleges affiliated with the army. One of the main changes in the army in the post-1979 period was the establishment of a political guidance branch tasked with overseeing and training army personnel in line with the Islamic Republic’s political ideology. This, over time, led to the army’s growing loyalty to the Islamic Republic and, as such, a shift in its pre-1979 doctrine.

Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The IRGC was established three months after the Islamic Revolution on Ayatollah Khomeini’s order. Thereafter, the IRGC Command Council was established to organize the new military institution. The army and police were in a state of collapse at the time. Indeed, the liberal interim government brought up the issue of the need for a functional and effective military force, which Khomeini endorsed.

However, that did not mean that the IRGC was to be a temporary organization. According to Article 150 of the constitution, the IRGC was to continue to play its role in guarding the revolution and its achievements. The corps was initially established to secure cities and villages, prevent the sabotage of state institutions, public properties and embassies, prevent the penetration of opportunistic and counter-revolutionary elements, enforce the interim government’s orders and execute the rulings of extraordinary Islamic courts. Its duties, however, were soon to expand and involve many other areas.

The IRGC comprises five branches: the land force, navy, aerospace force, Quds Force and the Basij volunteer paramilitary organization.

Though all of these forces have been crucial through the ups and downs of the post-1979 period, the Quds Force has been central to Iran’s regional influence. Established as the IRGC’s transborder unit during the Iran-Iraq War, the Quds Force gained prominence after the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. It was responsible for confronting the US in both countries and, according to many accounts, under the leadership of Qassem Soleimani, who was assassinated in Iraq by a US drone on 3 January 2020, was able to outmanoeuvre the US forces in many cases. The Basij, which is the most popularly present force within Iranian society, is tasked with recruiting, training and organizing volunteers in line with the overall goals of the Islamic Republic.

The current head of the IRGC is Hossain Salami, whose known anti-US rhetoric and credentials suggest that his appointment soon after Soleimani’s death is a response to the US’ so-called maximum pressure campaign of crippling sanctions.

Law Enforcement Force

The Law Enforcement Force was established in 1991 through the integration of two of the oldest military organizations, the Gendarmerie and the Shahrbani, both established during the Qajar era in the 19th century. The force’s main duties are related to internal security, notably sabotage, terrorism and internal turmoil. As such, it is not involved in the country’s military strategy in the region and beyond. The head of the force is Hussain Ashtari, who assumed his post in March 2015.

Iran’s total number of military personnel is 513,000, of which 420,000 are in the army and 123,000 are in the IRGC. The Law Enforcement Force has 150,000 personnel. Iran’s armed forces are, therefore, among the biggest in the region. Despite this, Iran’s military expenditure has for years been the lowest in the Middle East. In 2019, the military budget was only 3.2 per cent of the national budget, compared to over 10 per cent in neighbouring countries. Nevertheless, because of its flourishing domestic military industry, Iran is believed to have one of the most powerful armed forces in the region.

It is also important to note Iran’s regional strategy of ‘forward deterrence’, aimed at facing and mitigating threats abroad. Because of the asymmetry in Iranian-Israeli military capabilities, with the latter armed with nuclear warheads, Iran set about assembling a group of like-minded allies to deter Israel conventionally. Over time, this alliance-building effort grew to include many states and movements in the region, called the axis of resistance. The common ideology of this alliance is to resist US domination and Israeli occupation. Though this has burdened Iran’s military, the forward deterrence argument is perceived positively in Iran. This was made clear after the assassination of Soleimani, the architect of the strategy, with millions of Iranians mourning his passing and painting him as a national hero.

Iran’s effective support of its allies in Lebanon, Iraq and Syria against common rivals and enemies has elevated the country’s military position across the region. Its show of power in the Persian Gulf in June 2019, which saw its down a US spy drone, signalled its military capabilities and development. Although the numbers of missiles and other military equipment at Iran’s disposal remains undisclosed, many sources indicate they are on the rise.

In remarks to graduates at the military University of Imam Hussain, Ayatollah Khamenei underlined the need for the continued development of the armed forces to tackle the challenges posed by Iran’s enemies, suggesting Tehran will continue to bolster its military capabilities in the face of the maximum pressure campaign.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Iran’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: