Mahjoubi Aherdane, a controversial but generally liked figure, is not one man but four: politician, poet-writer, artist-painter and the oldest living icon of Morocco’s Amazigh ethnic group. He was married to Mireille de Gasquet (Meryem Aherdane), of French origin, who died in 2015, and is the father of two.

Born in 1924 in Oulmès, a village in the Middle Atlas Mountains, Aherdane embarked on a military career to “go beyond the tribe, go higher with feet rooted in my culture”, as he put it. During the French colonial era (1912-1956), he was a member of the National Council of Resistance and one of the leaders of the Liberation Army. After independence, he served as governor of the Province of Rabat. Just one year after independence, he founded the Popular Movement and became its leader. This political party was the first Amazigh organization in a position of authority and is still functioning. Aherdane served in eight Moroccan governments (from 2 June 1961 to 1 April 1985) as minister of national defense, minister of agriculture, minister of state for national defense, minister of telecommunications, minister of state responsible for cooperation and finally minister of state without a portfolio. As a politician, Aherdane is known to be a great and seasoned visionary.

He is the symbol of Amazigh culture par excellence. He embodies authenticity in all its dimensions: his clothing, his gestures, his words and his way of life. He has remained loyal to his inner ‘peasant’ and ‘small citizen’. He founded the Amazigh Civilization and History Review, which was censured after its tenth edition due to the opposition of conservatives, who saw in the Amazigh social movement a political threat. He helped to establish the Tifinagh magazine and the Agraw Amazigh and Tidmi weeklies, all of which are dedicated to the promotion and protection of Amazigh culture.

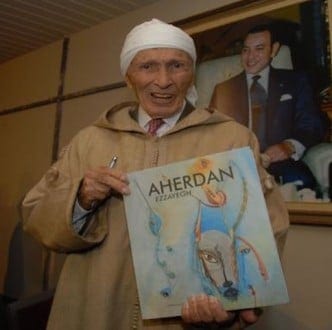

Aherdane is also a gifted artist. Painting for him is a way of both growing and relaxing. He likes to remind Moroccans that a politician can paint and that art makes better politicians. As an artist, he releases himself from the divisions and hierarchies of policy-making, freely expressing emotions and thoughts without obeying any ‘political’ censorship which, he says, “always disturbs the playing of the actors on the chessboard of power”.

Perhaps remarkably, Aherdane was successful before technology reached Morocco. Despite the technological gap, he communicated with the world through his paintings, which began to circulate in exhibitions worldwide in 1957 (USA). Thereafter followed Paris (1962), Montreal (1967), Geneva (1969), Copenhagen (1969), Algiers (1969, 1974), Rabat (1971, 1976, 1981), Dakar (1974), Baghdad (1974), Cairo (1983), Grenoble (1985), Laâyoun (1985), Fez (2005, 2007) and others.

Aherdane’s art fascinated many intellectuals, including Fatema Mernissi and Zakia Daoud. Mernissi saw in him the perfect reflection of the tenth-century Andalusian scholar and imam Ibn Hazm. Ibn Hazm wrote a book about love, the famous Tawq al Hamama (Dove’s Necklace), in which he not only described his own feelings, but also encouraged Muslims to become more rational by studying their irrational feelings, starting with the incomprehensible attraction and repulsion of love. When asked by Mernissi, Aherdane acknowledged the role of his mother (a carpet weaver and artist) in his creativity. According to him, the women weavers of the Upper and Middle Atlas have for millennia been reproducing signs that preceded writing, and he wonders why the United Nations and the World Bank classify these women as illiterate. For him (as well as Mernissi), these women are the only remaining guardians of knowledge that goes back to the Neolithic period and which exists only on carpets and at pre-historic sites.

For Daoud, Aherdane’s artworks are “drawings, bizarre shapes, based on but transcenders of animals, horses, birds, swans, eyes, and lines sometimes become monsters, herbal material, trees”.

Aherdane is a poet who couches his verse in both Amazigh and French. His poems are less political than his paintings. They are concrete. They express everyday life. Aherdane is the author of It Remains That (published by Julliard); Aguns’n Tillas (poetry collection); The Mass will… (1976); Iguider, or the Myth of the Eagle; A Poem for Standard (novel); Fire Irons (novel); and Baraka Khlass or Sign of the Times.

Finally, Aherdane is a true symbol of the cultural mix that defines the Moroccan landscape. He is a man faithful and loyal to himself, to his principles, to his country, to his friends, to his culture, a brave man, equal to himself in his words and deeds. It is this integrity that makes Aherdane a force for all Moroccans, Arabic- and Amazigh-speaking alike. As Moha Khettouch put it in his book Aherdane or The Passion of Liberty (2000), Aherdane is an extraordinary person, with an objective, the multiple aspects of a political actor often overshadowed by the chronic and again hurt including, for wearing a personal style that roots his logic in his Amazigh territory: a land rich with Moroccan identity but also ancestral plurality and diversity.