Introduction

The population of the Kingdom of Morocco was estimated at 36.87 million in 2020, with a population growth rate of 1.1%, compared to 1.22% in 2019. And a gender ratio estimated at one male for every female.

According to World Bank data, the population of the Kingdom in 2019 was estimated at about 36.47 million, with males accounting for 49.61%, and females 50.39%, with a gender ratio of 98.5 males for every 100 females.

The last census took place in September 2014 and put the population at 33.8 million. The census highlighted the changing structure and size of Moroccan households between 1982 and 2014. The average family size declined from 6 in 1982 to 5.8 in 1994, and from 4.8 in 2004 to 4.2 in 2014.

Between 2012 and 2017, the total population growth rate was 6.96 percent, with an average annual growth rate of 1.4 percent over the five years.

Muslims – predominantly Sunnis – make up 99 percent of the population as per The World Factbook. The remaining 1 percent is made up of Christians, Jews, and Bahais.

Arabic is the official language of the country along with several Berber languages. French is mostly used in business, government, and diplomacy.

During the second half of the twentieth century, Morocco became one of the largest immigration countries in the world, creating large and widely dispersed immigrant communities in Western Europe. The Moroccan government has encouraged immigration since its independence in 1956, to secure remittances to finance national development and as a breathing space to prevent unrest in rebellious (often Berber) regions.

A wave of family immigration followed in the 1970s and 1980s, with an increasing number of second-generation Moroccans choosing to become naturalized citizens of their host countries. Spain and Italy emerged as new destination countries in the mid-1980s, but the imposition of visa restrictions in the early 1990s led Moroccans to increasingly migrate either legally by marrying Moroccans already in Europe or illegally to work in the underground economy.

Women have begun to form an increasing proportion of these migrant workers. At the same time, some highly skilled Moroccans went to the United States and Quebec, in Canada.

In the mid-1990s, Morocco developed into a transit country for asylum seekers from sub-Saharan Africa and illegal migrant workers from sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia in an attempt to reach Europe via southern Spain, the Spanish Canary Islands, or Spanish enclaves in North Africa, Ceuta, and Melilla. Forced expulsions by the Moroccan and Spanish security forces did not deter these illegal immigrants or assuage security concerns in Europe.

However, thousands of other illegal immigrants have chosen to remain in Morocco until they have earned enough money to continue traveling or permanently as a “second best” option. The launch of the Regularization Program in 2014 legalized the status of some immigrants and gave them equal access to education.

Age Groups

Estimates of the age structure in 2019 AD reveal that the Moroccan population is classified as young. 26.3% of the population is under the age of fourteen, 43.1% is under the age of 25 years, and 46.32% of the population falls in the age group (25- 59) years old, but those 65 years of age and over estimate only 10.9% according to official social indicators.

The average number of family members in Morocco in 2019 was 4.4 individuals (4 members for an urban family, and 5.2 members for a rural family).

The fertility rate in Morocco was estimated at 2.38 children/woman (2.12 in urban areas and 2.8 in rural areas) (2018 estimates).

The average life expectancy of the population per year in 2021 AD is approximately 73.56 years (71.87 years for males, 75.34 years for females).

Areas of Habitation

In 2020 AD, the United Nations estimated the population density at 82.7 people / km2. Casablanca is the largest city in Morocco and is the main commercial and industrial center. Casablanca is a city of French colonial rule. It began to develop as a port in the mid-nineteenth century, and by 1913 it had become a sprawling city of 12,000 people.

However, the first French Resident-General in Morocco, Louis Hubert Leoti, determined to make Casablanca the center of trade and business and launched a massive urban planning campaign to turn it into one of the most luxurious cities. By 1921 AD, its population reached 110,000, and that number rose to 965,000 by 1961 AD. In 2018 AD, the population of Greater Casablanca was estimated at 3.684 million (CIA World Factbook), and this number includes satellite cities, such as Mediouna, Mohammedia, and Nouaceur.

Casablanca is not the country’s political capital: it seems that Leoti found it fragile and lacking in majesty and history, making Rabat, which lies in the north of the country along the coast, the administrative center of the country. Consequently, he shifted the focus on urbanization away from inland cities, such as Fez and Marrakech, to coastal cities, even though the population of the main Moroccan cities is very large (in 2018, the population of the capital, Rabat, reached 1.847 million, Fez 1.184, Tangiers, 1.116 million, and Marrakesh) 976 thousand, and Agadir 888 thousand).

46% of the population lives in the governorates of the Atlantic coast between Tangiers and Settat, and in some of these governorates, especially Greater Casablanca and the area around Rabat and Salé, where most of the population is urban (92% and 84% respectively). Despite the dense urbanization of these regions, they are still considered one of the most productive areas in terms of agriculture – the majority of the arable lands in these regions and in the interior parts of the country (inhabited by 50% of the population), such as the urban areas of Fez and Marrakech Nevertheless, some governorates are predominantly rural and sparsely populated, especially in the far northwest and south. The percentage of the population of the areas that formed the former Spanish Sahara does not exceed 3% of the total population, which is largely urban (94% in El-Ayoun).

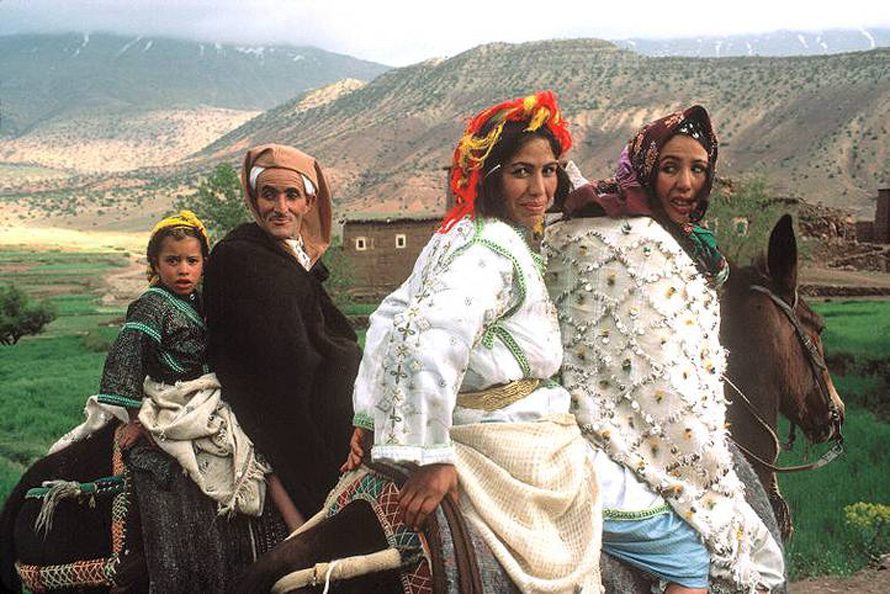

Ethnic and Religious Groups

The raw statistics would suggest that Morocco is a remarkably homogeneous society culturally and religiously. Muslims form 99 percent of the population and Christians 1 percent, and Jews number about 6,000. The population is 99 percent Arab-Berber, though three main languages are spoken, Arabic, Berber or Tamazight (both official languages), and French (as the language of business, government, and diplomacy). In reality, this apparent homogeneity is misleading: both linguistic and religious identities are contested.

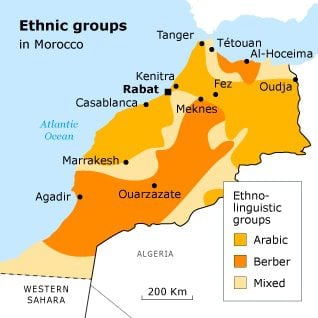

The essential difference between the Arab and Berber peoples in Morocco is linguistic. Berber was the language of the mass of the population until it became Arabized through religion, trade, and urban-based government. Arabic is a Semitic language, but Berber is a non-Semitic language of the Afro-Asiatic group and has many variants (variously considered languages or dialects) across North Africa.

Berber activists generally refer to their community as Amazigh, though that is an expression derived from one of the three distinct dialects of Berber: Tashlhit (spoken in the High Atlas), Tamazight (spoken in the Middle Atlas, and Tarifit (spoken in the Rif). According to the Moroccan Census Office, 89 percent of the population aged over five in 2004, spoke a dialect of Arabic, 14 percent spoke Tashlhit, 9 percent spoke Tamazight, and 5 percent spoke Tarifit.

The picture is further complicated by the annexation of the Western Sahara, whose people speak a distinct Arabic dialect known as Hassaniya (0.7 percent of the total population of post-1975 Morocco).

Historically, the Berbers and Arabs resembled each other in tribal and kinship organizations. In times when the central government of the state was weak, as it was before colonial rule in the first half of the 20th century, kinship-based systems, real or fictitious, provided the basis of a functioning economic and social solidarity. Whether a tribe’s members spoke Berber or colloquial Arabic was a matter largely of contact with state officials.

In neither case were these literary languages. Historically, literary Arabic was confined to official and religious business, and both Berber and colloquial Arabic were spoken according to what was needed in a particular environment. The linguistic boundaries shifted: over time, Berber tribes were increasingly Arabized.

During the colonial period, Berber-speaking tribes posed a much stronger armed resistance than did the Arab-speakers of the plains and cities. The French (and to a lesser extent Spanish) authorities attempted to deal with this by co-opting the Berbers as a socio-ethnic group, recognizing their particularities, and emphasizing their differences from the Arab speakers.

This led to the famous Berber Dahir of 1930, a decree that established a separate legal system for areas that the French determined were culturally Berber. This was the main impetus to the early nationalist movement, which was connected ideologically to similar movements in the Arab East, so the nationalist movement identified itself in terms of Arabic.

After independence, literary Arabic was emphasized in education, and the national educational system marginalized the Berber languages. French retained a prestigious position in administration, government, and culture, and vernacular dialects of Arabic and Berber remained in use for everyday purposes. As a result, the linguistic distinctions cannot be mapped cartographically with any certainty, beyond a very general assertion that some areas are predominantly Arab-speaking and some predominately Berber. The same person may use different languages and different forms of the same language on different occasions.

There is essentially a complex system of triglossia, that is, alternative uses of the same language. A variety of vernacular Moroccan Arabic is used in intimate, informal, everyday purposes; an ‘educated’ variety, exclusively spoken, Middle Moroccan Arabic is used between strangers for formal, official purposes (an estimated 40 percent of the population can use this variety, and greater numbers can understand it); written, literary Arabic, is, of course, confined to those who are literate.

Side by side with this triglossia, is a functioning trilingualism, in spoken Berber, Arabic, and French. It is estimated that 10 percent of people can use French effectively for reading, writing, and speaking, but many more can use a more or less pidginized form.

To complicate matters further, a diglossia is emerging in Berber as well, the result of Berber identity politics since the early 1990s. In 1994, King Hassan II declared that Amazigh ‘dialects’ were ‘one of the components of the authenticity of our history’, and the government began to accommodate demands for Berber to be recognized, by setting up broadcasting in each of the three main dialects. The preamble to the 1996 Constitution made it clear that Arabic was the official language of the state and made no mention of Berber.

Berber activists nevertheless set up associations and newspapers, and militants proposed a redefinition of Morocco harking back to its pre-colonial and pre-Islamic heritage. After Mohammed VI came to the throne, a Berber cultural revival began, and the government in 2001 set up the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM), with a huge budget (over USD 100 million) to be spent on cultural development. Music helped cultural growth through cassette tape recorders, CDs, and then the Internet. In 2010, a Tamazigh TV station was set up, broadcasting nationally.

The 2011 Constitution continued this process: its preamble speaks of Moroccan unity as founded on the convergence of its Arabo-Islamic, Amazigh (Berber), and Saharo-Hassani components, nourished by African, Andalusian, Jewish, and Mediterranean currents. Article 5 states that Arabic is ‘the official language of the state’ (‘la langue officielle de l’État’, emphasis added) while Tamazight constitutes ‘an official language of the State’ (‘une langue officielle de l’État’, emphasis added).

As an official language, there is a growing movement for Berber to be formalized and written, based on the Tifinagh script, the historic consonantal script used by the Tuareg people of the Sahara. A modified version of that script is used in a few elementary schools, but it serves more as a marker of cultural purity than as a practical alternative to the Arabic or Latin scripts.

Religion

Constitutionally, Morocco is not only a Muslim country – 99 percent of the population is officially described as (Sunni) Muslim – but its King is specifically the leader of a religious community, the ‘Commander of the Faithful’ (amir al-muminin). This title is based on a claim of direct descent from the Prophet Muhammad: the King’s legitimacy is therefore defined by both faith and descent in a way that the legitimacy of secular presidents, even those of religious republics, is not.

The regime emphasizes its religious aspects, but Moroccan Islam is not homogeneous and has not been historical. Moroccan Islam is Sunni, of the Maliki school of law, yet there are great differences in practice across the population. Traditionally, Moroccan Muslims have paid great respect to the tombs of holy men and women, known in Morocco as marabouts. Although Islam has no concept of canonization, marabouts possess the quality of baraka (blessing), a mixture of personal holiness and inherited worth that can pass from father to son and to other members of the family.

Sometimes this inherited prestige was based, like royal legitimacy, on the descent from the Prophet Muhammad, whose descendants are known as sharifs in Morocco. The tombs of marabouts and sharifs dot the Moroccan countryside; living marabouts who stood outside both state and tribal political authority provided mediation in disputes and sanctuary for fugitives. Some marabouts were adepts of forms of Islam’s mystical path, Sufism. The great Sufi brotherhoods (tariqas), which were founded in the Middle Ages, exercised considerable power and enjoyed great wealth.

Both marabouts and the leaders of tariqas played a generally conservative role during the colonial period and lost political influence in the post-independence period, but mass pilgrimages to important tombs still attract many people, particularly women. The Islamic movement that developed in Morocco in the late 1980s and early 1990s criticizes these phenomena as irreligious innovations because they speak of intercession between God and believers which, Islamists say, has no place in a strict interpretation of their faith.

Jews have a long history in Morocco. Their communities predate the coming of Islam, and their residents were later joined by many waves of Jewish refugees.

There were two main groups of Jews: those who originated in the Moroccan countryside, particularly in the High Atlas, and a sort of upper class, often descended from families expelled from Spain after 1492. By the 19th century, some Jews had left the countryside for the cities, although rural communities remained well into the 20th century, speaking the local language, Berber or Arabic.

Refugees from Spain continued to speak a dialect of medieval Spanish among themselves and even had Spanish names. These educated men were part of a Jewish network across the Mediterranean that enabled them to make fortunes from trade. They often acted as commercial representatives of the sultans. Consequently, the sultan extended protection to the Jewish communities and in every town, the Jewish milla (quarter) was close to the walls of the royal palace or the residence of the governor. On the other hand, there were rigorous restrictions on dress and behaviour imposed on them, and Jews were sometimes the object of mob violence, especially in times of economic difficulty. During the French Protectorate, the Jewish population of Morocco thrived, at least until World War II, when, under Nazi pressure, the Vichy authorities mistreated them, while King Mohammed V protected them.

As a result, during the nationalist movement and the early independence period, Jews were both favoured by King Mohammed V and, on occasion, reviled by nationalists, who resented the creation of the State of Israel. Many Jews emigrated, some to Israel, some to Europe and North America, including French Canada, but others remained in Morocco, closely attached to the royal family, sometimes even as economic advisors to King Hassan II. Because they also had good contacts with the Israeli elite, they acted as diplomatic go-betweens, and Morocco was an important player in the negotiations leading up to Anwar Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem. Thus, although the Jewish community declined from about 250,000 at the end of World War II, there is still an important community of 5,000-6,000 people, synagogues are open, and Jewish sites are preserved.

Socio-economic Composition

The Moroccan population can be divided by culture (Arab and Berber) and by wealth. These two main categories are not necessarily coincident.

The cultural distinction between Arabs and Berbers is not the critical determinant of standard of living and quality of life. That results in more regional and educational factors than ethnic ones. It is certainly not religious, as nearly all Moroccans are Sunni Muslims. The Berber heartlands are in the mountains and the deserts, although the desert inhabitants of the provinces of the former Spanish Sahara speak a dialect of Arabic. It is true that these regions are often poorer, but not always. Many Berbers migrate, either to the cities of the coast, where they have to Arabize but often remain poor or to Europe where they have to learn European languages but often grow much richer than they could in Morocco.

The most blatant disparities are in income, education, and health and are reflected in the differences in life expectancy between rural and urban populations, the latter generally having better education and health conditions. These advantages are only partly the result of higher income. Medical service and schools are provided in greater abundance in urban than rural areas – there are more doctors and more specialists in Rabat and Casablanca than there are in the Rif mountains, in the north, or the Sous, in the south.

Income Distribution and Poverty

The rapid growth of the Moroccan economy, especially since 2000, has lifted many Moroccans out of extreme poverty but has resulted in a more unequal distribution of wealth.

The upper 20 percent of income earners earn nearly half (47.88 percent) of the income of the country, while the lowest 20 percent earn 6.5 percent. These figures have not changed much since 2001 when the figures were 47.7 percent and 6.47 percent, respectively (data are from the World Bank).

Yet the number of Moroccans who are extremely poor has fallen sharply. A report by the Moroccan Census Office in 2007, analyzing the distribution of wealth, divided the lower end of the income spectrum according to measures of relative poverty and vulnerability defined by the World Bank. The calculations were complicated: relative poverty was based on an index of the income needed to buy enough food to provide 1,984 calories a day, tied to an index of non-food items. The vulnerability was defined by multiplying this index by 1.5.

The report stated that between 2001 and 2007, relative poverty declined from 15.3 percent to 8.9 percent across the entire country, from 7.6 percent to 4.8 percent in urban areas, and from 25.1 percent to 14.4 percent in rural areas. The index of vulnerability declined as well (from 22.8 percent to 17.5 percent nationally, from 16.6 percent to 12.7 percent in urban areas, and from 30.5 percent to 23.6 percent in rural areas). Other measures of deprivation showed the same pattern, in terms of absolute income and food supply.

While the general pattern shows a rapid decline in poverty, the pattern is much more varied at the regional level. Measures of relative poverty applied to individual provinces showed that relative poverty was lower than the national average on the coast between Casablanca, Rabat, and Tangier but was much higher in the rural areas of the north-west and around the great inland cities – Fez, Meknes, and Marrakesh.

But the provinces of the former Spanish colony of Western Sahara were all richer than the rest of Morocco, testifying to the amount of politically driven investment there. The same variations exist at the local level: in the province of Meknes, for example, the commune of Mrhassiyine has a poverty index of 35.9 percent and a vulnerability index of 27 percent while in the small town of M’haya the figures are 4.8 percent and 11.8 percent respectively. The distance between the two places is less than 20 kilometres, but the cultural distance may be huge, and that has an economic aspect: while income may be low in the countryside, people produce their own food; income may be higher in towns, but housing is more expensive.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Population’ and ‘Morocco’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: