Dana Hourany

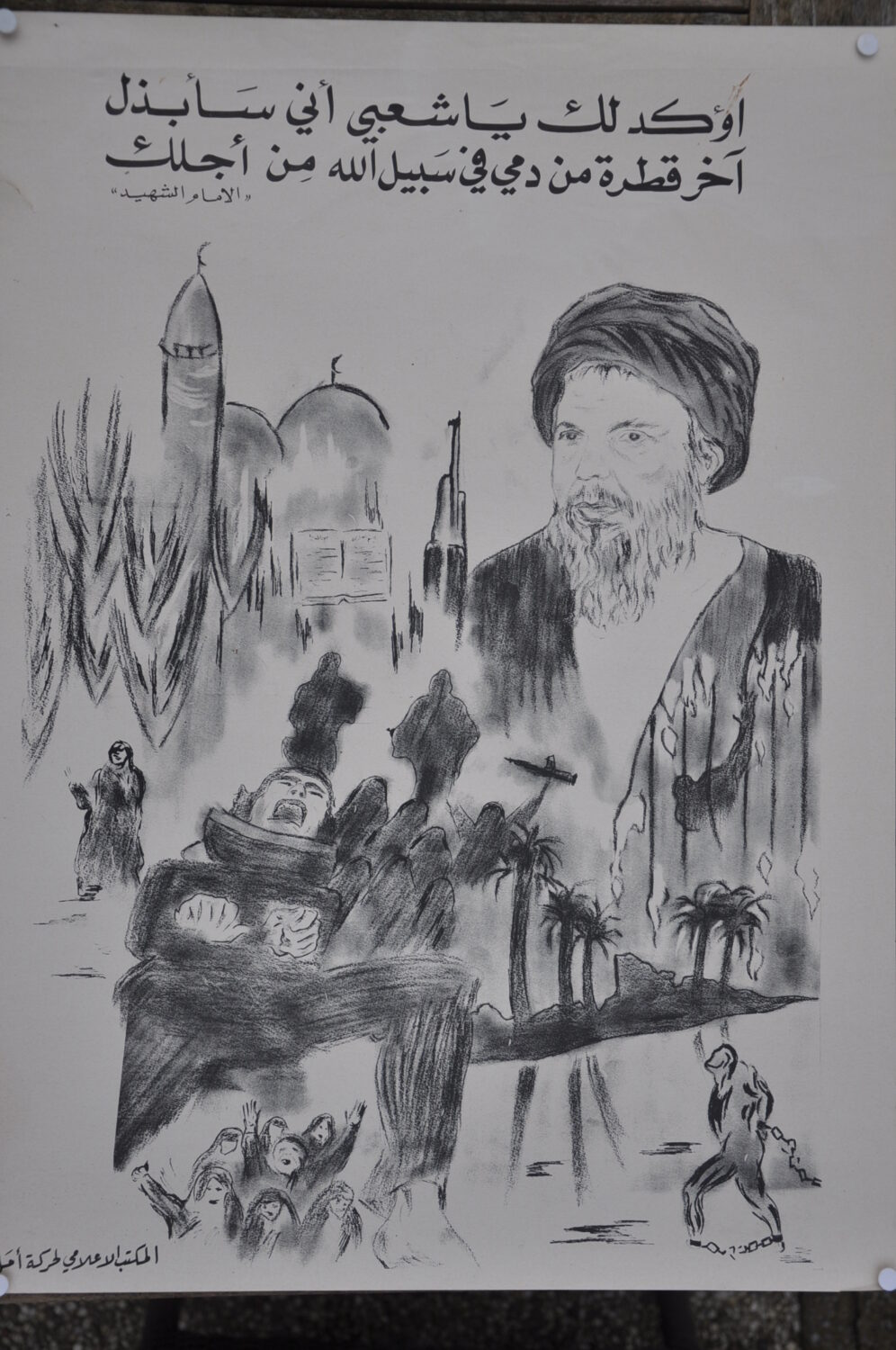

A tall man with a striking figure and a commanding presence, he spoke with a calm yet an assertive tone, tinged with a Persian accent. Admired by many for his charisma and words of justice, Musa al-Sadr, known as Imam Musa or Imam al-Sadr, would become one of Lebanon’s most revered religious clerics throughout its most tumultuous time, the 1975-1990 civil war.

Born in 1928 in the holy city of Qom, Iran, to a renowned Shia Muslim family, his father, clergyman, Ayatollah Sadr al-Din al-Sadr, urged the young man to pursue his education in Islamic Jurisprudence.

As a Shia cleric, al-Sadr obtained a degree in Law and Economics from Tehran University.

Al-Sadr’s family is said to hail from the Lebanese southern village of Shhour, close to Tyre – the Imam’s first destination upon visiting Lebanon in 1957.

During his visit, al-Sadr met with Sayyid Abd al-Hussein Sharaf al-Dine, an esteemed Shia religious leader in Lebanon. Impressed by his personality and characteristics, Sayyid Sharaf al-Dine asked his peers to name Imam Musa as his successor.

Sharaf al-Dine died in 1957 and his wish came to fruition in 1959. Having settled in Lebanon in 1960, Imam Musa was confronted with an arduous task and a challenging reality. The Shia of Lebanon at the time were dispersed between the Biqaa Valley, Jabal ‘Amil (south Lebanon), and the southern suburbs of Beirut. Without access to proper education, employment opportunities, and little to no political representation, the Imam set off on a journey of political, social, and economic reform.

His activity was brought to a halt on August 1978 when he disappeared on a visit to Libya alongside his two companions. His legacy, however, has withstood the test of time and is commemorated on August 31 of every year.

A man of unity and dialogue

The Imam championed inter-faith and intra-faith dialogue and worked to pull the Shia community out of the narrative of victimhood. In 1969, he was elected as Head of the Supreme Islamic Shia Council, which he created to prop-up the role of the Shia community in the country’s complex political and religious web.

He was also known for doing a great many small deeds. One incident that has been passed down through oral tradition is that of Uncle Antiba’s – a Christian ice cream vendor in the city of Tyre whose business nearly collapsed due to calls for boycott – on grounds of his faith – by Shia competitors. Having confided in the Imam with his predicament, al-Sadr headed to the shop, bought ice cream and his Shia supporters followed suit.

“When he is not here with us, we are like orphans,” Uncle Antiba is quoted as saying in a short video documenting the incident.

Unlike Iran’s first religious leader Ruhollah Khomeini, al-Sadr did not subscribe to the call for a Velayat el Faqih or the guardianship of the Islamic Jurist that was bolstered by the Islamic Revolution. He would go on to attend masses, give seminars in churches, call for Shia-Sunni unity and dine with Maronite politicians.

Although the Shias were ostracized and the conflict with Israel on the southern borders was brimming, the Imam sought to find reconciliation even within the most polarized camps.

“Israel was an imminent threat to the south and the Imam knew action had to be taken,” Faten Mhanna, Lebanese journalist and producer of a documentary on the Imam told Fanack.

“There were those who supported a national resistance movement against Israel and those opposed to the idea – most notably the Christian Phalangists led by the Gemayel family. Nevertheless, the Imam would sit with the Christian leaders to discuss solutions.”

When the civil war broke out in 1975, al-Sadr was devastated. He went on a three day hunger strike in a Beirut mosque in protest.

For him, civil peace and national unity were essential tools to guard the country against foreign threats.

Actions not words

One of Imam Musa’s most notable achievements, was establishing the Imam Musa al-Sadr Foundation, comprised of elementary, secondary, technical schools, orphanages, shelters, a nursing college, and the Institute of Islamic Studies.

The Technical Institute of Jabal ‘Amil – a trade school that provided the impoverished children of southern Lebanon a chance at education – became a refuge for many children who lost their parents during the Israeli invasion and incursions on south Lebanon that began in the late ’70s.

In a televised interview, Imam al-Sadr stated that his goal is “to be in service of the exhausted, the tortured and the dispossessed… Although we were able to take the beggars off of the streets of Tyre, a lot needs to be done to tackle the causes of poverty… We hope that this institution will be a giant leap in our mission to serve the area’s destitute.”

The funding, he added, was from local donors, the Lebanese diaspora, and the French government.

At the cusp of the Civil War in 1974, al-Sadr established the Movement of the Dispossessed, a social reform movement to defend the Shia during conflict, accompanied with its military branch, the Amal movement – a prominent player in today’s Lebanese politics.

However, his stance on civil peace was unwavering. When the northern non-Shia towns of Al-Kaa and Deir al-Ahmar were besieged and heavily shelled during the civil war, the Imam addressed Shia audiences in neighbouring towns and villages urging them not to participate in any violence saying, “any bullet fired at Deir Al-Ahmar or Al-Kaa… is fired at my house, my heart and my children.”

Division within the community

Despite al-Sadr’s widespread popularity, two separate political movements were emerging within the Shia community. The first abided by the Imam’s nationalistic take that prioritized bolstering the Shia’s integration in Lebanese society and politics. The second group followed the ideology of the late cleric Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah and the Iranian-backed Shia party Hezbollah that supported large-scale Shia revolutionary and transnational ideas.

The main disagreement lied on views related to the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). The latter had turned the southern villages of Lebanon into guerrilla bases that Israel continuously targeted.

While Al-Sadr was sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, he refused to sacrifice the Shia community in a fight that would exacerbate their suffering.

He especially warned against forming foreign allegiances. In a 1977 speech, he said, “do we, as Lebanese, suffer from lack of internal allegiances that we need to add a new foreign axis? I hope all Lebanese, Arabs, and Iranians understand this message. To the politicians trying to exploit these foreign relationships at the expense of the nation and the sect, they should enjoy the life that God blessed them with instead.”

A lost dream

According to Mhanna, what set the Imam apart from today’s politicians was his humility and openness to differences.

“He did not like being glorified nor put on a pedestal. He always repeated that he was there to serve the people and always maintained a pragmatic approach in his speeches, unlike the aggressive populist approach of today’s politicians,” the journalist said.

“He welcomed opposing opinions and was open to negotiations. Today you’re called a spy, a traitor, or even un-Lebanese for expressing dissent,” she added.

Close family friend of al-Sadr, Mohammad Sharaf el-Dine told Fanack that the Imam was an accessible figure who kept his door open for people to come forward with their grievances, no appointments needed.

“He charmed everyone with his compassion. No matter their religion, no one felt out of place,” Sharaf el-Dine said. “If he were alive today, the different Shia political factions of current Lebanon would be united under his hand. It would be a different country.”

The Imam vanished on August 31, 1978 on a trip to Libya where he traveled with two companions, Sheikh Mohammad Yaakoub and journalist Abbas Badreddine, in the hopes of convincing Muammar Gaddafi to curb his military support for Palestinian fighters in Lebanon.

He was last spotted shortly before he met with Gaddafi. What happened afterwards remains a mystery. Some point the blame at Libya for murdering or imprisoning the Imam, others believe Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini wanted to eliminate a potential rival.

Alive today, the Imam would be 94.

“We did not lose a person, we lost a nation. Look at Lebanon today, riddled with sectarianism, hatred, and calls for federalism. Everything the Imam called for is being erased. We need to keep his memory alive to instill hope in reviving the dream of the Lebanon he worked for,” Mhanna said.