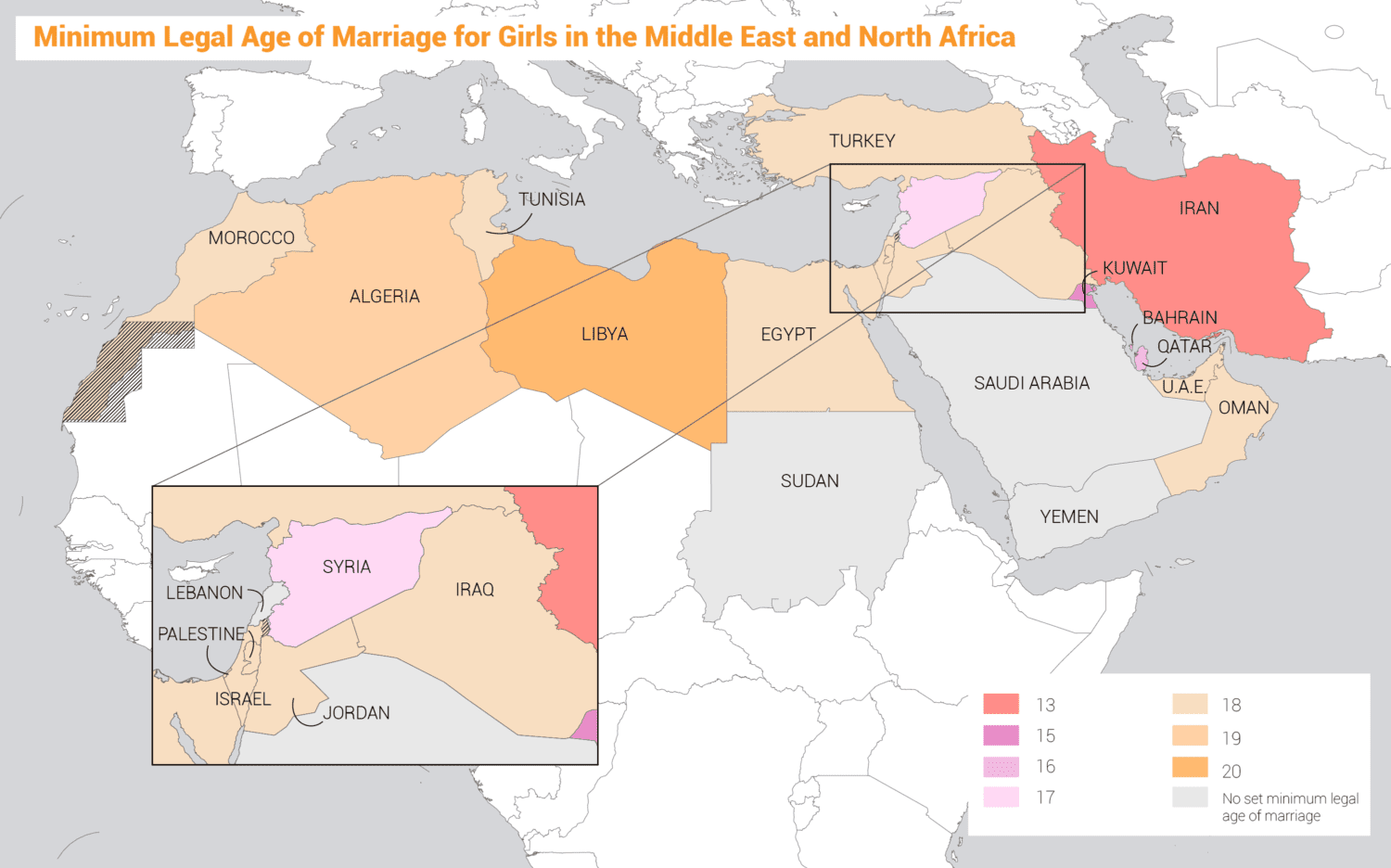

Underage marriage (also called minor marriage or child marriage) may be defined as marriage under the legal age. The legal age in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) varies between 13 (in Iran ) and 20 in Libya, while in most countries, there are legal loopholes or exceptions to the stated legal age, which make it possible for girls to get married before reaching the legal age. Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Sudan have not established a legal age of marriage.

Child marriage particularly affects victims from countries facing war and extreme poverty. In addition to the short-term damage it inflicts on the young bride or groom, child marriage is also the cause of longer-term suffering, including rape, unwanted pregnancies, lack of access to education and the continuation of poverty in the family.

Despite progress in family law in many countries, such as Morocco where the legal marriage age was raised from 14 to 18, and changes in family structure in the countries of the MENA region and the concomitant emergence of nuclear families, underage marriage still exists.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund ( UNICEF ), in the region taken as a whole, 15 per cent of women aged 20-24 were married before the age of 18 (world average: 19 per cent). Two per cent of these women were married before the age of 15 (world average: 5 per cent). On a country level, there are major differences, ranging from 2 per cent married before reaching 18 in Tunisia to 32 per cent in Yemen.

In Iran, more than forty thousand girls under the age of 15 are married off each year, according to the Center for Human Rights in Iran. Exemplary of the many exceptions to the legal age in the region, Iranian girls under 13 can get married with the consent of the father or a guardian and a judge.

Underage marriage has many complex reasons, ranging from poverty, conflict, culture to religious dogma. According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), child marriage stories are remarkably similar from one country and region to the other, with drivers such as discriminatory gender roles, including the expectation in some cultures that sons should support parents in old age while daughters “belong” to their in-laws; lack of access to education, which drives girls out of school and increases the risk of them marrying young; poverty, including food insecurity; efforts to control girls’ sexuality and lack of access to comprehensive sex education, contraception and abortion; financial incentives, driven by dowry and “bride price” practices; and social pressures.

| Country | Female | Male |

| Algeria | 19 | 19 |

| Bahrain | 16 | - |

| Egypt | 18 | 18 |

| Iran | 13 | 15 |

| Iraq | 18 | 18 |

| Israel | 18 | 18 |

| Jordan | 18 | 18 |

| Kuwait | 15 | 17 |

| Lebanon | - | - |

| Lybia | 20 | 20 |

| Morocco | 18 | 18 |

| Oman | 18 | 18 |

| Palestine | 18 | 18 |

| Qatar | 16 | 18 |

| Saudi Arabia | - | - |

| Sudan | - | - |

| Syria | 17 | 18 |

| Tunisia | 18 | 18 |

| Turkey | 18 | 18 |

| UAE | 18 | 18 |

| Yemen | - | - |

Minimum legal age of marriage for girls and boys. Source: Girls Not Brides

Poverty

Poverty is a corollary of a host of related marginalizing and crippling conditions, such as illiteracy, ignorance of rights, and lack of choice. Divorce, domestic violence, drug addiction, and psychological problems abound in such contexts. All of these factors push parents—or, in the absence of the father, just mothers—to marry off their daughters as soon as a husband can be found. This haste to “get rid” of the girl is accentuated by the perceived need to preserve the “honour” of the family and avoid social shame and humiliation.

According to Girls Not Brides, a global network of organizations working to end child marriage around the world, parents, by marrying off their daughters early, are not doing so out of cruelty but rather out of fear that they will not be able to provide for and protect them, believing that marriage might protect their daughters from harm while also providing them with a level of financial stability.

Another increasingly common motive related to poverty is the need for money. This phenomenon is attested especially in Egypt, where young girls are sold off to wealthy husbands in the Gulf. The same phenomenon is found in Morocco, where poor families “send-off,” for money, their daughters to older and already married richer husbands in the wealthy Gulf countries. Most sexually exploited minors in the MENA region come from economically fragile families.

In these families, female illiteracy is the norm, eliminating choice. For example, the Moroccan network Azzahrae conducted a case study in 2012 that showed that the illiteracy rate of underage married girls’ parents is 53.7 per cent for mothers and 27.9 per cent for fathers. Indeed, it is rare to find an educated mother marrying off her daughter to “get rid” of her. The level of education, especially that of the mother, is crucial also in providing appropriate family care for her daughters, such as reinforcing them against various problems such as drug use, especially during adolescence.

In addition to illiteracy, and sometimes because of it, the already poor situation of the family may be worsened by family dislocation. Most sexually exploited minors come from unstable families characterized by the absence of the father, children born outside marriage, adoption, or domestic violence. In such situations, girls do not generally develop a strong relationship with their parents, whom they often see as bad examples. The absence of a parent role model, parental authority, and discipline create deep psychological divisions in the family.

Religion

Underage marriage is also being legitimized by the religiously-based perceived need to take “ preemptive measures ” to “protect” girls from spinsterhood. With the strong return of Islamic conservatism after the so-called Arab Spring in 2011, more and more fatwas on the benefits of marrying very young girls have been issued in the region. Social media conversations indicate a fear of well educated and Westernized women and a preference for younger “inexperienced” girls. In these often heated debates, theological justifications—such as the fact that the Prophet married his last wife, Aisha, when she was nine—are put forward.

Paradoxically, and despite the risk of social problems in poor families, the social value of honour is especially strong among the poor in the MENA region. Underage marriage may thus be justified because it “saves the family’s honour,” as is the case in Jordan, for example. Underage marriage, extreme violence, and suicide are attested in the case of the Moroccan Amina Filali, who committed suicide in 2012 after she was obliged to marry her rapist to save her family’s reputation. This incident pushed many feminist NGOs and human-rights organizations to demonstrate against underage marriage. This activism led to a change in Article 475, from allowing a rapist to marry his victim to decreeing a 30-year prison term for such a crime.

Conflict and Insecurity

Particularly in conflict-ridden countries like Syria, Yemen and Libya, women and girls are at risk.

Based on a study on child marriage in Syria, published in 2018, Girls Not Brides, found that although 13% of Syrian women aged 20 to 25 were married before they turned 18 even before the conflict began, child marriage is a growing problem for Syrian girls in refugee communities in Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Turkey. In Jordan, for instance, figures show an increase over time, from 12% of registered marriages involved a girl under the age of 18 in 2011 to 18% in 2012, 25% in 2013 and 32% in early 2014. In Lebanon, 41 % of young displaced Syrian women were married before 18 and, given that many marriages are unregistered, these figures may be much higher.

Research carried out by HRW revealed that conflict and insecurity, as well as other crises such as natural disasters, can heighten the risk of child marriage. “In a crisis, parents may be struggling to feed and protect their children. They may see marrying a daughter off—earlier than they would have in peacetime—as a way to reduce their burden and make it more feasible to care for their remaining children,” Heather Barr, acting co-director of the Women’s Rights Division at HRW, told Fanack.

“They may mistakenly view marriage as a way to protect a daughter from risks associated with the conflict, including the risk of sexual violence. They may simply be overwhelmed and unable to cope. And in cultures where a marriage involves a financial transaction, like the payment of dowry or “bride price”, child marriage may offer a parent stressed by the conflict a financial gain or an opportunity to avoid having to pay a dowry themselves. Many parents, faced with the terrible choices imposed by a conflict, genuinely believe that swiftly arranging a marriage for their daughter is their only or best option to try to protect her and the rest of the family.”

According to Barr, it is often difficult to gather accurate data on child marriage, even during times of peace, because of gaps in data or child marriages being concealed due to illegality. “In the context of conflict in these three countries, gathering accurate data is even more challenging. But Girls Not Brides has documented an increase in the number of child marriages among Syrian girls displaced by the conflict and there is every reason to believe that pattern also holds for Yemen and Libya. ”

The extreme violence and sex slavery that have accompanied the rise of jihadism in 2014-2015 put women at even greater risk. Very young girls were being sold in the marketplace like sheep. This threatens any hope women might have of legal rights, such as the setting of the marriage age at 18. Just before the outbreak of the war in Yemen in March 2015, there was talk of ending child marriage, a window of hope in the country that had, at that time, the most cases of underage marriage of girls. With war raging in Yemen and the extremely unstable situation throughout the region, conflict and war present a bleak and frightening vision of the future of underage marriage there.

“We know that when families experience great stress due to factors such as a conflict, child marriage can become a coping mechanism, especially in an environment where child marriage already exists,” Barr told Fanack. “This is why conflict or other crises bring a serious risk of an increase in rates of child marriage.”

Consequences of child marriage

Girls marrying at a young age face numerous hardships, including complications during pregnancy and childbirth, violence, limited educational and economic opportunities, as well as less freedom and the inability to socialize with children their age. These consequences are likely to negatively impact the region’s youth, who may be inclined to normalize a social system that allows child marriage and family violence.

Facing this situation, international organizations such as UNICEF have publicly called for the need to help children, notably because of “the conflicts in the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen, volatility in Libya and upsurges of violence in Palestine that are exposing children to extreme risks, including death, injury and displacement, as well as forced recruitment into armed groups and early marriage.”

In Yemen specifically, Amnesty International said that “the protracted conflict has exacerbated discrimination against women and girls and left them with less protection from sexual and other violence, including forced marriage.” The New Humanitarian published several testimonies about child marriage in Yemen, including the one of Safa’a, married at 14, who said, “brides [are supposed to] celebrate on their wedding day. But I was crying when I had to leave my mother’s room because I knew I couldn’t achieve my dreams. My future would be in my husband’s hands, not mine.”

A solution to end this phenomenon cannot come quickly enough to save thousands of girls from an unfortunate fate. It is a topic that is currently being addressed through the UN Sustainable Development Goals, where countries have committed to a target of ending all child marriage by 2030.

“Many organizations, including those in the Girls Not Brides network, are working on the ground, country-by-country, to urge and help governments achieve that target,” Barr said.

“The response from governments has been varied. Some have taken important steps, such as reforming their laws to bring the age of marriage in line with international law (which says that the age of marriage should be 18, with no exceptions); others have developed national action plans for how to achieve the 2030 target. But some governments have been very slow to prioritize this issue or have ignored it or even pushed back against efforts at reform. In countries experiencing conflict, it can be especially difficult to compel governments to pay attention to the need to end child marriage.

Whatever the case and whatever the justification used, these girls are the victims of acts in which they have no say. They are sexually exploited and are denied the right to choose in important decisions, such as marriage, on which their entire lives depend.

Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in union before age 18

Source: UNICEF

Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in union before age 15

Source: UNICEF