An overview of Palestinian political prisoners held in Israeli jails, hunger strikes, and the 2011 prisoner swap deal between Israel and Hamas.

Introduction

Since its occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, Israel has detained over 750,000 Palestinians (men, women, the elderly and children) through a systematic set of regulations that violates basic human rights. The Palestinian prisoner issue thus has always featured high on the agenda in the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, as the Palestinia National Authority believes the outcome of any political arrangement with Israel should include the release of all Palestinians detained for political reasons as well as those suspected of being a security threat.

According to Israeli Military Order 1229 (1988), administrative detention in Palestine is legal, empowering military commanders to hold an individual in custody for up to six months if there is ‘reasonable grounds to presume that the security of the area or public security requires the detention’ (the military order is based on British Mandatory legislation concerning Administrative Detention). According to the Israeli Human Rights organization B’Tselem ‘security is interpreted in an extremely broad manner such that non-violent speech and political activity are considered dangerous’. Israel routinely renews these detention orders without trials, sometimes for up to several years.

The military judges base their verdicts regarding administrative detentions on confidential information, which is not provided to the detainee or his attorney, leading to a continuous practice of imprisonment without trial or and renewed imprisonment after the completion of a sentence.

A report published by Le Monde Diplomatique in June 2012 states that the aim of these deliberate arrests is to control the Palestinian territories from a distance. By imprisoning a person based upon administrative detention law, Israel can harvest information about their family and social or political ties. The report explains that the Israeli security services ‘use continual arrests to recruit collaborators, infiltrate Palestinian society and add to their considerable knowledge of Palestinian political, social and daily life’.

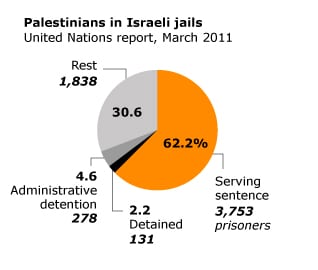

According to figures of the Palestinian NGO Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, 5,271 political prisoners were held in Israeli jails as of May 2014. Of these 5,007, 516 were serving life sentence, and 137 were in administrative detention. The majority of these prisoners are male, but over the last 43 years, Israel has arrested and/or detained an estimated 10,000 women. Each year an average of 700 children under the age of 18 are prosecuted under Israeli military orders. In May 2014, 17 Palestinian women were held, and 196 children, of whom 27 under the age of 16. According to the Israeli military law, Palestinian child prisoners may be sentenced in military courts from the age of twelve, which violates both international and Israeli juvenile law.

Furthermore, the UN Committee Against Torture expressed concern about the ‘inordinately lengthy periods’ of detention and reported that it could constitute cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. ‘Administrative detention thus deprives detainees of basic safeguards, including the right to challenge the evidence which is the basis for the detention, warrants are not required, and the detainee may be de facto in incommunicado detention for an extended period, subject to renewal.’

About 85 percent of the Palestinian prisoners, whether men, women or children, have suffered torture, humiliation or intimidation during their incarceration. These methods are used to obtain a confession from the detainees, as most of the cases do not come to trial, and a confession is needed to justify the conviction.

Twenty out of the twenty-five Israeli prisons and military detention centres for Palestinians are located outside the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which violates Article 76 of the Fourth Geneva Convention: ‘Protected persons accused of offences shall be detained in the occupied country, and if convicted they shall serve their sentences therein.’

In 2003, the convicted Palestinians were integrated into Israel’s civil prison system, under the authority of Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security service. This action normalizes the occupation by blurring judicial boundaries between the occupied and occupying country.

Palestinian prisoners suffer from all kinds of discriminatory regulations behind bars. The prison authorities have reinforced the 2007 split between Fatah and Hamas by separating prisoners affiliated to Islamist political parties from prisoners belonging to nationalist/secular political parties. Prisoners are also separated according to their citizenship status, distinguishing between whether someone is from a refugee camp or a village. This leads to more division and isolation among prisoners.Hunger strikes

In June 2011, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu announced tougher restrictions on Palestinians’ prison rights – in an effort to secure the release of one of its soldiers, Gilad Shalit, captured by Hamas in a cross-border raid in Gaza in 2006 – expanding the use of solitary confinement, reducing family visits, preventing access to books, educational programs and new clothes. The main reason for this measure of collective punishment was the lack of progress in the negotiations on the release of the Israeli soldier.

To draw attention to the continuous imprisonment without charge and solitary confinement, about 2,000 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails embarked on hunger strikes that began on Prisoners’ Day, 17 April 2012, under the slogan: ‘We will live in dignity.’ They have built on a protest that has resulted in deals to release two inmates who refused food for prolonged periods.

Khader Adnan, 33, the first prisoner to begin a hunger strike in the current wave, refused food for 66 days before agreeing to a deal that should end his four months in administrative detention without charge or trial. He was released in August 2012.

Hana Shalabi, 30, was released and deported to Gaza after 43 days on hunger strike. Her family home is in the village of Burqin, near Jenin, in the north West Bank. Shalabi had previously been held for 25 months under administrative detention, but was freed in October 2011 under the prisoner swap but re-arrested on 16 February 2012. According to Amnesty International, when Shalabi agreed to the deal, her medical condition was weak. In addition, she was denied access to independent lawyers, which is in violation of basic human rights.

In March 2012, Israel assassinated Mahmoud Hanani in Gaza, one of the freed prisoners in the swap that took place in October 2011.

Agreement

The mass hunger strike that lasted nearly a full month gained a lot of support. Protests and marches in towns and villages across the West Bank were taking place regularly with Israel responding to them with teargas, rubber bullets and a water cannon. In Gaza, besides protests and rallies the hunger strike also featured in sermons at Friday prayers. People around the world started sympathy hunger strikes.

Israel realized that this wave of protests would increase its negative image, emphasizing the illegality of the administrative detention. Also, Israel was aware that if one of the hunger strikers were to die, the outcome could have serious implications for stability and security conditions on the ground. Therefore, an agreement was reached on 14 May 2012 with the Israeli Prison Service (IPS) to meet certain core demands.

According to Addameer, who was representing the hunger strikers, ‘the written agreement contained five main provisions: the prisoners would end their hunger strike following the signing of the agreement; there will be an end to the use of long-term isolation of prisoners for “security” reasons, and the 19 prisoners will be moved out of isolation within 72 hours; family visits for first degree relatives to prisoners from the Gaza Strip and for families from the West Bank who have been denied visits based on vague “security reasons” will be reinstated within one month; the Israeli intelligence agency guarantees that there will be a committee formed to facilitate meetings between the IPS and prisoners in order to improve their daily conditions; there will be no new administrative detention orders or renewals of administrative detention orders for the 308 Palestinians currently in administrative detention, unless the secret files, upon which administrative detention is based, contains “very serious” information.’

Even though about 2,000 Palestinian prisoners subsequently ended their hunger strike, a month later, in June 2012, Addameer observed that Israel had failed to respect the agreements. It renewed the detention of prisoners and failed to improve their daily conditions. The Israel Prison Service of placing put some of the hunger strikers in solitary confinement without justification and beat them. Also, the Israeli army arrested more citizens in the West Bank.

Relaunched hunger strikes

As a result, prisoners relaunched their hunger strikes. Among them were a soccer player in Palestine’s national team, Mahmoud al-Sarsak, who was detained without charge for almost two years and was on a hunger strike for over 90 days, until Israel released him in July 2012, and Akram al-Rekhawi, a diabetic prisoner, who was on a 102-day hunger strike. Addameer said that Akram al-Rekhawi faced ‘an imminent threat to his life’, while independent doctors were denied access to him.

In September 2012, the International Committee of the Red Cross expressed its extreme concern about the deteriorating health of three Palestinian detainees: Samer al-Barq, Hassan Safadi and Ayman Sharawneh. These men were close to death after a hunger strike of more than three months, refusing to take liquids and vitamins. The Palestinian detainees contested Israel’s arbitrary methods of administrative detention, long-term isolation and the renewed administrative detention orders against them. According to a report issued by Human Rights Watch, Israeli military authorities renewed al-Barq’s administrative detention order seven times. Al-Barq went on a hunger strike on 15 April 2012 but resumed eating on May 14th, with the end of the mass hunger strike by Palestinian detainees. He began a second strike on May 21st, when the Israeli military once again renewed his administrative detention order.

Hassan Safadi was previously repeatedly detained by Israel without charge, most recently from 2007 to 2010. In May 2011, the Palestinian Authority detained him for 45 days, then released him. Israeli forces arrested him again a week later, on 29 June 2011, suspecting him of being ‘a prominent activist of Hamas and that he is endangering public order’, however without providing him or his lawyer with a concrete reason for his detention. Safadi went on hunger strike from 5 March to 14 May 2012, and renewed the hunger strike on 22 June, when the Israeli military renewed his administrative detention order for another six months.

Israel had previously sentenced Sharawneh to 38 years in prison, but released him after ten years, in October 2011, as part of a prisoner swap with Hamas for the release of the captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit. On 31 January 2012, Israel rearrested and detained Sharawneh at his home in Dura, near Hebron, in the West Bank on suspicion of unspecified ‘activity that endangers the security of the area’. Addameer later said that a special military committee had revoked his previous release order on the basis of secret evidence. Sharawneh began his hunger strike on July 1.

Israeli military forces arrested al-Issawi, also on a hunger strike, in 2007, and a military court sentenced him to seven and a half years in prison. Israel released him in December 2011 during the second phase of the Shalit prisoner swap, but re-arrested him on 7 July 2012, on the basis of a special military committee’s decision to revoke his release.

According to Addameer lawyer Fares Ziad, who visited Samer al-Barq, Hassan Safadi and Ayman Sharawneh, ‘Israel not only deprives all three a fair trial but also continues to severely mistreat them in the forms of physical brutality and psychological torture, as exemplified by the bargain to give Ayman Sharawneh pain medication for his back only if he ends his hunger strike’. Addameer confirmed that Samer al-Barq has ended his third hunger strike as of 18 October 2012, but no further details were available.

Israel is continuing its practice of administrative detentions on a daily base, with a 40 percent increase in the number of children held in military detention since December 2011. As of 1 October 2012, there were 4,596 Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli prisons and detention centers. Each year approximately 500 to 700 Palestinian children, some as young as twelve years of age, are detained and prosecuted in the Israeli military court system. The most common charge is for throwing stones. The overwhelming majority of these children are detained inside Israel in contravention of Article 76 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.2011 prisoner swap

In October 2011, in a prisoner swap between Israel and Hamas, Israel agreed to free 1,027 Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the release of Gilad Shalit.

The prisoner swap took place in two phases: the first phase saw the release of 477 Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the Israeli soldier on 11 October 2011. The second phase took place on 18 December 2011, freeing the remaining 550 Palestinian prisoners.

Of the first 477 prisoners, 131 were returned to Gaza, while 130 were sent home to the West Bank. Six were Palestinians residing in Israel. 203 prisoners were deported to foreign countries, with 40 barred from Israel and Palestine. Addameer for Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association described deportation as a ‘forced displacement in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention‘.

The indirect talks between Hamas and Israel, that lasted five years, were brokered by Egypt, with the involvement of Germany. Notably missing from the list are two high-profile Palestinians, namely PFLP Secretary-General Ahmed Saadat and Fatah leader Marwan Barghouti.

The prisoners’ swap was welcomed with much joy on the Palestinian side, as many of these detainees were serving life sentences.