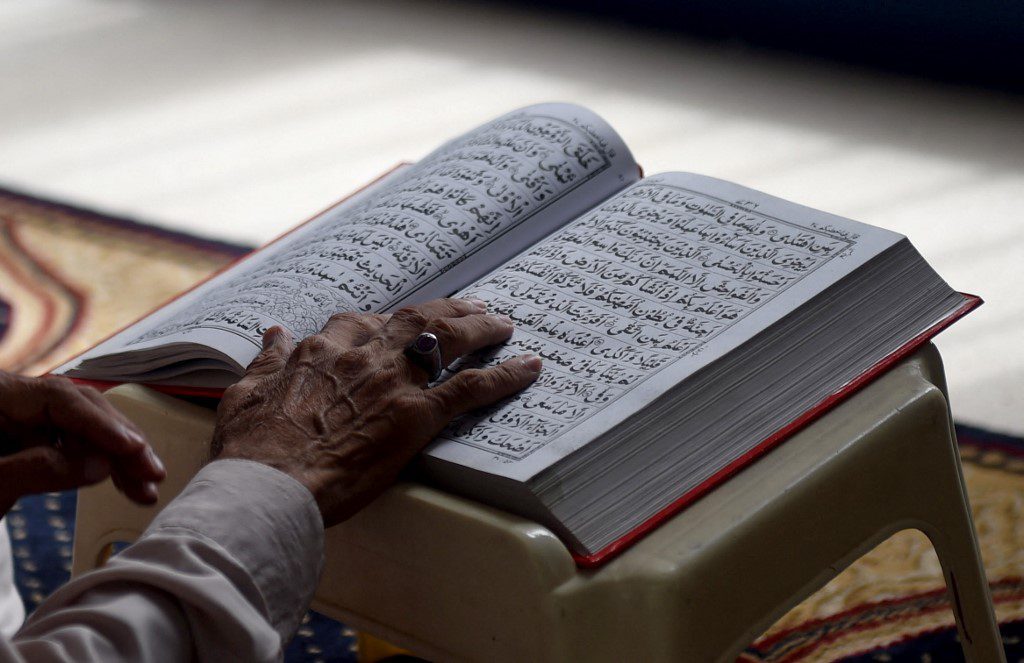

Researcher Kristina Nelson Focuses on the Quran as a Phonetic Phenomenon, not as a Written Text

Youssef Sharqawi

The orientalist position on the Quran is not new. The controversy over the Quranic text appeared early since John of Damascus (1), Moses Ben Maimonides (2), Thomas Aquinas (3), and Peter the Venerable (4). The latter was the first to encourage the project of translating the Quran into a Western language. The first translation into Latin appeared by the British Robert of Ketton (5) between 1136 and 1157. After that, translations continued, and orientalists expanded in studying the sciences of the Quran. Orientalist schools became prominent, such as the French and German schools, until a different study appeared by the American Orientalist Kristina Nelson.

Before Nelson, most Orientalist studies of the Quran focused on the linguistic aspect. Orientalists considered the Quran a word-based linguistic book, as they used philology to study it. They delved into the tiniest linguistic details found within the Quranic text. They tried to return it to what they imagined to be its origin in other eastern languages. Therefore, their extrapolation was fragmental due to their adoption of old research methods.

Kristina Nelson, who visited Egypt nearly 40 years ago and settled in Cairo, did a different extrapolation, perhaps the first of its kind. Such a move was an attempt to reach a deeper understanding of the Quran. Nelson interpreted the Quran primarily as a phonetic phenomenon, not as a written religious text similar to religious texts that preceded it. Nelson saw the Quranic phenomenon as part of the core of religious devotion that transcends the auditory aspect. For her, it was a piece of the soul of cultural and social practices. In other words, the Quranic phenomenon was for her art of pure value.

According to Philip de Schiller, Nelson’s approach to the Quranic phenomenon changed the way we understand the Quran, as well as the way we listen to it. Nelson explains the emotional forces of the Quran when reciting it, with what it evokes of poetic rhymes, that is, how its rhythm evokes meaning. She explains intonation, social context, and the debate about music in Islam. She describes the sound of the Quran as it occurs in daily life. For her, the Quran was a subject of daily reception and perhaps of Tajweed and recitation at its origin. Such an approach rarely occurred in orientalist studies.

According to Nelson, the mission of the Quran’s written text is not to preserve it from change, as the basis for safeguarding it is oral reading. She says that the written text is not the absolute reference but only one part of the Quranic phenomenon. Such a phenomenon includes, among others, the sound and the preserved Slate (6).

Reading knowledge is based on many sources, more than just the written word. Interestingly, the distribution of the first written Quranic text among the people accompanied having a reciter who taught them the art of recitation.

By reading her study, we see that Kristina belongs to the impartial orientalist front, which achieves a kind of objective equivalence between the vocabularies of any issue under discussion.

Over time, orientalist studies produced methods of dealing with Islam and a style of discourse, according to their approach and perception. It was a means of drawing the East and presenting it. That approach was not only to the West but also to the people of the East themselves.

When the Orientalists wanted to study the Quran for the first time, they have had ancient goals. The list of purposes included knowing the religion of the enemy and demonizing it. After that, the orientalists changed their approach. They wanted to learn about the religion of peoples to colonize and exploit them. Then, the balance of global power changed with the rise of Europe militarily and civilly. The orientalists wanted to study the Quran devoid of the previously mentioned factors. At that point, studying the Quran became an epistemological purpose. However, such an approach came with a burdened past. It faced an epistemological heritage that dealt with the Quran out of denial. Belittling dominated the orientalists. Therefore, they fell into the dilemma of religious fanaticism.

While dealing with the Quran and its sciences, Nelson neglected the mentality that dominated other orientalists. She relied on self-tangencies and emotions to achieve a new orientalist path. Arabic fascinated her with sound, rhythm, and forms of grammar. Therefore, she read numerous times ancient Arabic literature. She was not satisfied with remote monitoring. She lived in Cairo as a listener, reader, and trainee of the art she loves. Such a thing made her study field-based, impartial, and devoid of passive purposes.

Sources:

1_ The Art of Reciting the Qur’an, Kristina Nelson, American Univ. In Cairo Press, 2001.

https://www.amazon.com/Art-Reciting-Quran-Kristina-Nelson/dp/9774245946

- Orientalism & the Quranic Studies: Past and Present, Dr. Raghda Adeeb Zidan, Tafsir Center for Quranic Studies (Arabic version).

- American Researcher Documenting the Recitation of Quran in Egypt, Ashraf Abu Al Yazeed, Dalida Magazine, second edition, July 2016 (Arabic version).

_____________________

(١) https://www.marefa.org/%D9%8A%D9%88%D8%AD%D9%86%D8%A7_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%85%D8%B4%D9%82%D9%8A

(٢) https://www.marefa.org/%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B3%D9%89_%D8%A8%D9%86_%D9%85%D9%8A%D9%85%D9%88%D9%86

(٣) https://www.marefa.org/%D8%AA%D9%88%D9%85%D8%A7_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%83%D9%88%D9%8A%D9%86%D9%8A

(٤) https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%A8%D8%B7%D8%B1%D8%B3_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A8%D8%AC%D9%84

(٥) https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%AA_%D9%83%D9%8A%D8%AA%D9%86

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of our bloggers. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Fanack or its Board of Editors.