Several recently published reports indicate that it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to eradicate IS permanently, regardless of how the world might fight it.

Introduction

In an interview with the newspaper Global Post on 14 October 2014, UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond said his country was determined to destroy the Islamic State, commonly known today as IS, but he did assert that ‘you can’t bomb an ideology out of existence’, an opinion many now share.

Several recently published reports indicate that it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to eradicate IS permanently, regardless of how the world might fight it. The reason, according to the reports, is not the military power of IS, nor the number of fighters or its enormous resources; it is rather the ideology that IS has created and worked so hard to disseminate.

This ideology would be difficult to uproot by force, even if a complete military and financial destruction of IS could be achieved.

IS’s propaganda is based on reviving the golden age of the historical Islamic caliphate, removing borders between the countries that were once part of that caliphate and ‘conquering’ and annexing new territories. The leaders of IS claim that the ‘rule of God’ would prevail in the lands under IS.

The Arabic term for the ‘rule of God’ is shara Allah, an expression that most Muslims take to mean justice and equality. That has been the discourse through which IS has been able to recruit thousands of young men and women and attract financial donations from around the world.

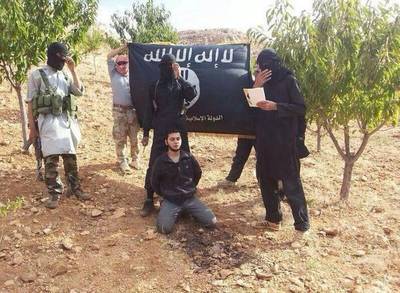

Observers are puzzled, however, by IS’s tireless efforts to publicize its extreme bloodiness. While nascent movements usually tend to present a better model to attract supporters, IS seems to rely on videos of beheadings, stoning, and killings as a major component of its propaganda.

According to specialists on Islamic groups, IS’s ideology was the joint production of four Egyptian extremists: Helmy Hashim, also known as Shaker Niamullah; Abu Muslim al-Masri, IS’s chief judge; another Abu Muslim al-Masri, who was, before his assassination, IS’s religious judge in Aleppo; and Abu al-Hareth al-Masri.

In addition to those, there was a man called Abu Shuaib, who recently defected from IS and lashed out at the group and its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, going back on many of his own fatwas (a ruling on a point of Islamic law issued by a recognized authority).

Since its beginning, IS members have shown a bloody, sadistic tendency. Their deeds have been criticized even by other Islamic extremists. Early in 2014, several al-Qaeda leaders denounced IS for its violence against civilians, a criticism that has led to a complete split between the two groups.

Retribution

A major element of IS’s propaganda is ‘retribution’. The group’s leaders claim that their ‘state’ would avenge the dignity of Islam and the Muslims whom ‘the infidels have long humiliated’. As used by IS, however, the term “infidel” is too loose; it could apply to anyone who disagrees with them, including Sunni Muslims who follow a slightly different interpretation of the Sharia from theirs.

In support of their argument, IS focuses on the marginalization of Sunni Muslims in Middle Eastern countries ruled by non-Sunni regimes. They also refer to Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Burma (Myanmar), and the prisons of Abu Ghreib and Guantánamo as places where Muslims were repressed by infidels.

In Syria, for instance, IS fighters use Assad’s crimes against civilians as a justification for their cruelty. They use ‘avenging the blood of Muslims’ as a slogan and focus on the fact that Assad and the bulk of his forces are Alawite, a minority that IS considers infidel. They also stress the fact that most of the victims in the Syrian war were Sunni Muslims.

But IS’s terror has gripped many Sunni Muslims themselves, and the group has committed genocide against religious minorities such as Christians and Yazidis, who have never been known to repress or marginalize Sunni Muslims.

Yale political scientist Stathis Kalyvas explains that IS’s ‘violence is not random…. It is targeted to weaken their enemies and strengthen IS’s hold on territory, in part by terrorizing the people it wishes to rule over’. He also asserts that the foundation of IS’s ‘power comes from politics, not religion’.

At the same time, some researchers believe that, by filming gruesome executions, IS aims to provoke the United States and its allies and drag Western powers back into combat in the region.

Political columnist Abdul-Rahman al-Rashid believes that IS’s horrific videos are made to keep the group in the media headlines: ‘The purpose is to shock the people with the harshest videos of beheading, killing unarmed civilians and stoning women. Even al-Qaeda has not gone that far’.

Rashid believes that IS is trying to show not only the ferocity of its fighters but also that the group is capable of recruiting more men and women through defiance, change, and promoting its own interpretation of Islam.

IS soon worked to promote its ideology. One of the last measures taken in this direction was to change the school curriculum in the areas it controls: terms such as ‘Syrian Arab Republic’ have been replaced with ‘the Islamic State’, and concepts of national patriotism and Arab nationalism have been completely removed.

The new curriculum stresses exclusive adherence to religion and that a Muslim land is one where God’s rule prevails. The new curriculum was rewritten with a strict commitment to IS’s interpretation of Islamic law, and, in a way, that justifies all the atrocities committed by the group.

Political analyst Michael Koplow sees IS’s ideology as ‘a revolutionary one seeking to overturn the status quo and to constantly expand, which makes it particularly capable of living on beyond the elimination of its primary advocate’.

He explains that IS’s ideology will not die just because its host body is decimated: ‘It will lurk around until another group seizes upon it and resurrects it…. The problem with Obama’s last speech was that it set an expectation that cannot be fulfilled.

Yes, IS itself may be driven from the scene, but the overall problem is not one that is going to go away following airstrikes or even ground forces’. The US president promised in his speech on 10 September 2014 to ‘degrade and ultimately destroy’ IS.

During a seminar at the Brookings Institution, Matthew Olsen, the director of the US National Counterterrorism Center said ‘it is absolutely impossible to both degrade and defeat IS, particularly over the long run. It is going to take time and part of that will mean working to secure a political transition in Syria’.

Some see the solution as laying the foundation for a modern school of thought that could emerge as an alternative to IS and to the Middle Eastern dictatorships that many blame for the existence of Islamic radicalism.

Political writer Abdul-Hamid al-Ahdab says that the solution is ‘to lay the foundation for an age of modern Islamic illumination and an era of secularism which guarantees freedom, equality and human dignity’.