In Iraq, Kurdish movements challenge state authorities, seeking autonomy and rights amid long-standing political tensions.

The Kurds were the first to realize that the Baath regime was not really interested in political accommodation: Baghdad never honoured promises of Kurdish autonomy. Negotiations broke down over the status of Kirkuk. Because of this, Barzani and his peshmerga resumed their armed struggle in March 1974. Unlike the 1960s, they now had to do without the support of the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) and the Soviet Union, who were now cooperating with the Baath regime. There were even armed confrontations between the Kurds and the Communists.

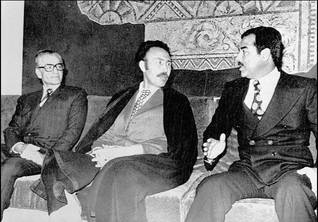

Even though the Baath regime had driven a wedge between its two most important political opponents, the Iraqi army could not defeat the Kurdish fighters. Only after Baghdad – in the person of the Vice-President and rising star of the regime, Saddam Hussein – met with the Shah of Iran in Algiers and concluded an agreement with him on 6 March 1975 could Baghdad successfully attack the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and eliminate it, for the time being, as a significant factor in Iraqi politics. The Shah ceased his support for the Kurds, in exchange for Iraqi concessions on control of the strategically important river boundary in the Shatt al-Arab.

The Treaty of Algiers, in which the boundary running through the Shatt al-Arab was shifted from the Iranian bank to the thalweg (the line connecting the deepest points along the river’s course) enabled Baghdad effectively to control the Iraqi-Kurdish conflict for the first time in many years. In order to weaken possible Kurdish political ambitions, especially during the Iraq-Iran War, in which the Kurdish parties sided with Iran, the Kurdish homelands were subject, during the following years, to large-scale devastation, and many thousands of Kurds were deported to ‘modern villages’ close to the big cities.

Many Kurds were killed in the process. The Assyrian villagers of Iraqi Kurdistan suffered the same fate – deportation and systematic destruction of their home territory – while urban Turkmen faced dispossession and (like the Kurds) ‘nationality correction’, under which they had the designation of ‘Arab’ forced on them.