State Borders

Like many other developing countries, Iraq is an artificial political entity. Its borders were drawn by Great Britain and France after World War I. Border issues have since been a source of tension, mainly with Kuwait (which many Iraqis regard as part of Iraq) and Iran (especially over the division of a shared waterway, the Shatt al-Arab).

The carve-up also placed a significant Kurdish population within Iraq’s borders, cutting them off from ethnic group members in Turkey. This too has led to intermittent tension and conflict. Iraq shares borders with Turkey (352 kilometres), Iran (1,458), Kuwait (240), Saudi Arabia (814), Jordan (181), and Syria (605) – 3,650 kilometres in total.

Iraq has a coastline of only 58 kilometres on the Persian Gulf (sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, especially by Arab-speakers), so it is almost landlocked.

Geography and Climate

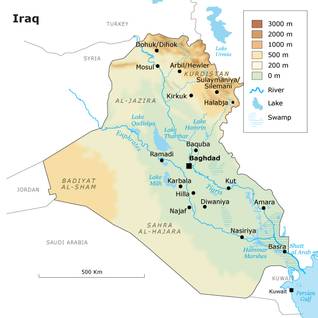

Iraq’s landscape is as varied as its people. The country can be divided roughly into four geographic zones: the rocky and sandy desert of the west and south-west; the mountains, hills, and steppes of the north and north-east, along the Turkish and Iranian borders; the hills and plains south of that region; and the marshy lowlands – the delta of the Tigris and Euphrates, where the rivers empty into the Persian Gulf.

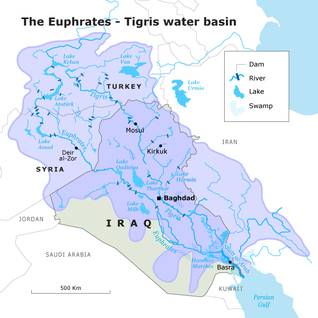

In the north the mountaintops reach 3,600 metres; in the far south the land is barely above sea level. Two great rivers run from north to south: the Tigris (1,418 kilometres in Iraq) and the Euphrates (1,213 kilometres). They join near al-Qurna (literally, ‘the Angle’), and from there to the Persian Gulf they form the Shatt al-Arab (literally, ‘the Arab Shore’), a river 185 kilometres long. Downstream from Baghdad the fall of both rivers is slight, and they flow lazily through the landscape.

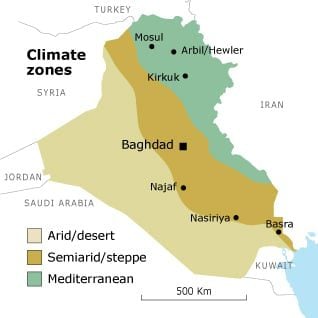

The desert region in the west and south-west is part of the Syrian Desert, which also covers large parts of Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. In the summer it is dry and hot, with daytime temperatures above 40 ºC degrees; at night, except in summer, temperatures can fall to around freezing.

In the summer, dusty, dry desert winds can last for many days and extend into adjoining regions. Because there is hardly any rain, there is little vegetation. Unfriendly to man and beast alike, this environment is very thinly populated.

Contrastingly, the living conditions in the mountainous north and north-east are favourable. Most of the precipitation there falls as rain or snow between November and April. From ancient times this has made cultivation of winter crops (and vegetables, fruit, and tobacco in the summer) and the raising of livestock possible.

During the winter the temperature can fall below 0 ºC; the summer is generally pleasant, compared with other parts of Iraq. Many well-off families in Baghdad have a second home in the Kurdish north or spend their holidays there, though such visits were limited whenever there was fighting between the government and Kurdish insurgents.

Further south the landscape becomes flatter. This is the delta of the Tigris and Euphrates, which has been under cultivation, with the aid of irrigation, since antiquity. Because of the higher average temperatures, palm trees grow in this part of the country. The south has extensive date-palm groves, and Iraq has, since ancient times, been the world’s leading exporter of dates.

In part because of the grinding poverty of the majority Shiite Arab population, the countryside in southern Iraq – in contrast, for instance, to Iraqi Kurdistan – leaves an overwhelmingly cheerless impression. In the summer the temperature reaches 50 ºC, forcing people to spend the hottest hours of the day indoors. In the far south, near the Persian Gulf, life in the summer is made even more unbearable by the high humidity.

Limited Water Supply

The Tigris and Euphrates both rise in Turkey; the Euphrates also flows through Syria before it reaches Iraq. Iraq is dependent on its neighbours for at least 80 percent of its water supply. Since the mid-1970s both Turkey and Syria have built many dams and reservoirs on the Tigris and Euphrates. The construction of these dams in the upper reaches of the rivers has led to a decreased flow of water downstream. This has had radical consequences, particularly for the Euphrates, because only a very small part of its flow is fed by rain that falls in Iraq.

It has been calculated that Iraq’s water supply will decrease by half after the completion of the planned water projects in Turkey. In the case of the Tigris, the situation is less serious, because it is also fed, wholly or in part, by tributaries that flow over Iraqi territory (such as the Diyala, which rises in neighbouring Iran). Over the past decades Iraq itself has constructed dams and reservoirs on the Tigris and Euphrates, for efficient water management and to generate electricity.

Draining the Marshes

Until a decade ago the south-east was an area of marshes that covered 20,000 square kilometres, the largest such region in the Middle East. It was the home of about a half million Madan, or Marsh Arabs, who are Shiites. By around 2000, only about 10 percent of these marshes remained. For decades the ecosystem had been under pressure from the construction of dams on the Tigris and Euphrates, which caused a drastic reduction in the amount of water flowing into the Marshes.

However, a devastating blow came when the regime of Saddam Hussein set out to drain the Marshes in the late 1980s. Dikes were built and the so-called Third River excavated, which drained water from the Marshes.

Before being drained, the Marshes had a unique flora and fauna. They were a natural nursery for fish and a stopping place for migrating birds. These Marshes performed an important function in the ecosystem of the Gulf region:

the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates, which had become polluted in their journey through Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, were largely purified in the Marshes by the natural effects of bacteria, oxygen, and sunlight, before they flowed into the Persian Gulf.

All this might have been lost forever, but with the fall of the regime, new hope arose for the region and its inhabitants, most of whom had been driven out. With the support of the local authorities, the Madan have removed several of the dikes. Satellite photographs show that, soon afterwards, about one fifth of the marsh area was once again under water. Restoration of the unique ecosystem and the provision of clean drinking water and sanitation systems for the 85,000 people remaining in the area are high on the list of projects the Iraqi authorities have submitted to the international donor community.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), with financial support from the Japanese government, has taken charge of the project, but after ten years there seems little enthusiasm among the expelled Madan for resuming their hard life in the Marshes (see also UNEP in Iraq: Post-Conflict Assessment, Clean-up and Reconstruction, 2007).

Enormous War Damage

The warfare of the last decades and the shortage of financial resources as a result, has had a major impact on nature and the environment. In Iraqi Kurdistan, for example, Baghdad implemented a policy of depopulation in the strategically important zones bordering Turkey and Iran, in an attempt to extirpate Kurdish nationalism. To prevent the return of the people who had been driven out, villages were levelled, wells poisoned, and landmines laid in the newly prohibited zones.

Military posts were established around population centres, atop hills and mountains. To protect these posts from guerrillas, all the vegetation in the vicinity was burned off, often several times a year, and the posts were surrounded with mine fields. The destruction of the environment in Kurdistan reached its maximum between 1987 and 1990. Deforestation also occurred, due to governmental neglect and a general popular disregard for the environment, leaving a landscape defined by long, barren mountain ridges.

Since October 1991, Kurdistan has no longer been under the control of the central government in Baghdad. Although the region has continued to experience severe economic problems, much has been done, with the support of Western aid organizations, to rehabilitate destroyed villages and clear land mines.

Land Mines

There are few war zones in the world where as many land mines were laid as in Iraq. It is estimated that there are still some eight to twelve million mines to be cleared – of all types and sizes, from heavy antitank mines to small antipersonnel mines – scattered over 2,500 locations. In addition to the mines planted in the 1970s and 1980s in the depopulated areas of Iraqi Kurdistan and around military posts, extensive minefields were laid along the borders with Turkey and Iran, in order to limit the movement of Kurdish peshmerga (guerrilla fighters), and to deter invasion by Iranian troops.

In many cases these minefields were not even plotted on military maps, which makes their clearance a time-consuming, costly, and dangerous task. Soil erosion in Iraqi Kurdistan has also meant that landmines laid around military posts on hill or mountain tops have slid or washed down to lower elevations. Every year many people, especially children who do not realize the danger, fall victim to uncleared mines. Information campaigns, marking danger zones and clearance activities, have led to a decline in the number of dead and wounded to an average of about thirty a month.

Unexploded ordnance also claims many victims each year. Across Iraq there are an estimated 2,200 locations where unexploded ordnance can be found. These include unexploded cluster bombs used by the anti-Iraq coalition in 1991, where parts of the cluster did not explode; they remain ‘live’ for years. The munitions also include unexploded shells and grenades.

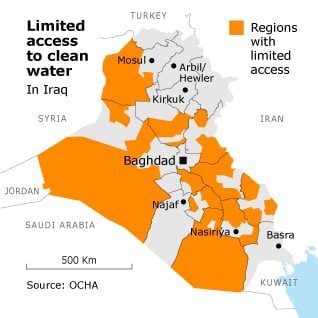

Water and Sewage

War causes serious harm to nature and the environment. For instance, in Iraq the 1991 anti-Iraq coalition bombardments destroyed many water and sewage systems and electrical generation facilities, which were intentionally targeted (contravening international conventions governing the conduct of war).

Without electricity, clean drinking water cannot be produced or distributed, and sewage cannot be pumped away and treated. Streets in poorer neighbourhoods turn into open sewers.

After the 1991 war, raw sewage and waste products from industry were dumped directly into the rivers. This has led to a sharp rise in the number of cases of diarrhoea and even cholera and has placed pressure on the whole ecosystem.

As in the social and political arena, nature and the environment of Iraq have been saddled with an inheritance that is the consequence of the frequent conflict and violence of the Saddam Hussein era.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Geography’ and ‘Iraq’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: