In May 2012, after yet another twist in Israeli coalition politics, Time magazine put Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu on its cover. “King Bibi,” the magazine called him, noting that “he has no national rival. His approval rating, roughly 50%, is at an all-time high. At a moment when incumbents around the world are being shunted aside, he is triumphant.”

The nickname stuck. Since his election victory on 17 March 2015, international and national media have praised and ruminated on the once and future Israeli leader: “King Bibi,” ruler of his country’s politics.

Indeed, in winning a fourth term, Netanyahu demonstrated his deep understanding of the forces driving Israeli political opinion. For much of the election campaign, commentators debated whether security or economic issues would prove the decisive factor in swinging the country’s voters. Netanyahu understood that it would be neither. Instead, for most voters, elections in Israel are a matter of cultural identification with “left” or “right.” Here, Netanyahu knew, he had a distinct advantage, which ultimately proved to be his trump card. Recognizing why Netanyahu had this advantage is central to contemplating Israel’s present and future.

A vote for the Israeli right may seem like a hawkish security vote against Arab enemies, real and imagined. Historically, though, it was actually directed more inward, against the entrenched socialist Zionist establishment that pioneered the state. Zionism always included a cacophony of voices, but in its formative period, most of those who left Europe to settle in the Land of Israel were from the “Labour Zionist” stream. This faction set up the pre-state institutions and, along with fellow migrants, came to dominate them. With the establishment of the state in 1948, this group founded the predecessor of today’s Labour Party. Culturally and economically, they dominated Israel and won every election in the state’s first 29 years.

Over time, though, the dominance of this elite engendered resentment. The first to voice their displeasure were the Mizrahim, Jews of Middle Eastern origin who fled the Arab world for the nascent state in the early 1950s. The immigrants were culturally distant from the Ashkenazi elite and at an economic disadvantage. Over time, they and many of their descendants came to feel that the Labour Ashkenazi establishment had shut them out of the halls of power. Finally, in 1977, resentment boiled over into anger, and right-wing leader Menachem Begin – with solid Mizrahim support – came to power, ending almost three decades of Labour Zionist rule.

The years that followed only added to the old elite’s woes. The numbers of religious, and especially Haredi (ultra-Orthodox), Israelis grew. In addition, a million Jews immigrated from the former Soviet Union. These groups, too, felt estranged from the cultural elite, which increasingly concentrated in what became known as the “State of Tel Aviv.” Finally, in 1996, this coalition brought about a surprise victory for the right-wing Likud prime ministerial candidate, Benyamin Netanyahu. Even then, press reports spoke of a new Israel, a Mizrahi-religious-Russian coalition toppling the old establishment and taking power.

Since 1996, the left’s demographic disadvantage appears only to have grown. Left and center-left political parties have tried various strategies to woo right-wing voters, most recently by appealing to the economic concerns that have garnered increased attention since the 2011 social protest movement. These strategies have failed.

Battle of Culture and Identity

Netanyahu understood that intuitively, it seems. Throughout the campaign, he pushed the buttons of culture-war issues. One day, he posted a harsh Facebook attack on the Yedioth Ahronoth newspaper, calling attention to what many on the right view as left-wing dominance in the media. He barred several judges from the annual Israel Prize for Literature because of their left-wing sympathies. This, too, called attention to widespread resentment of left-wing Ashkenazi domination of cultural institutions.

On election day itself, Netanyahu told supporters that left-wing and foreign-funded NGOs were driving Arab voters to the polls. But, again, he implied, the left-wing elite, moneyed and entitled, was using subterfuge to undermine the popular will of the real Jewish majority, the Mizrahi, religious and Russian-immigrant populace.

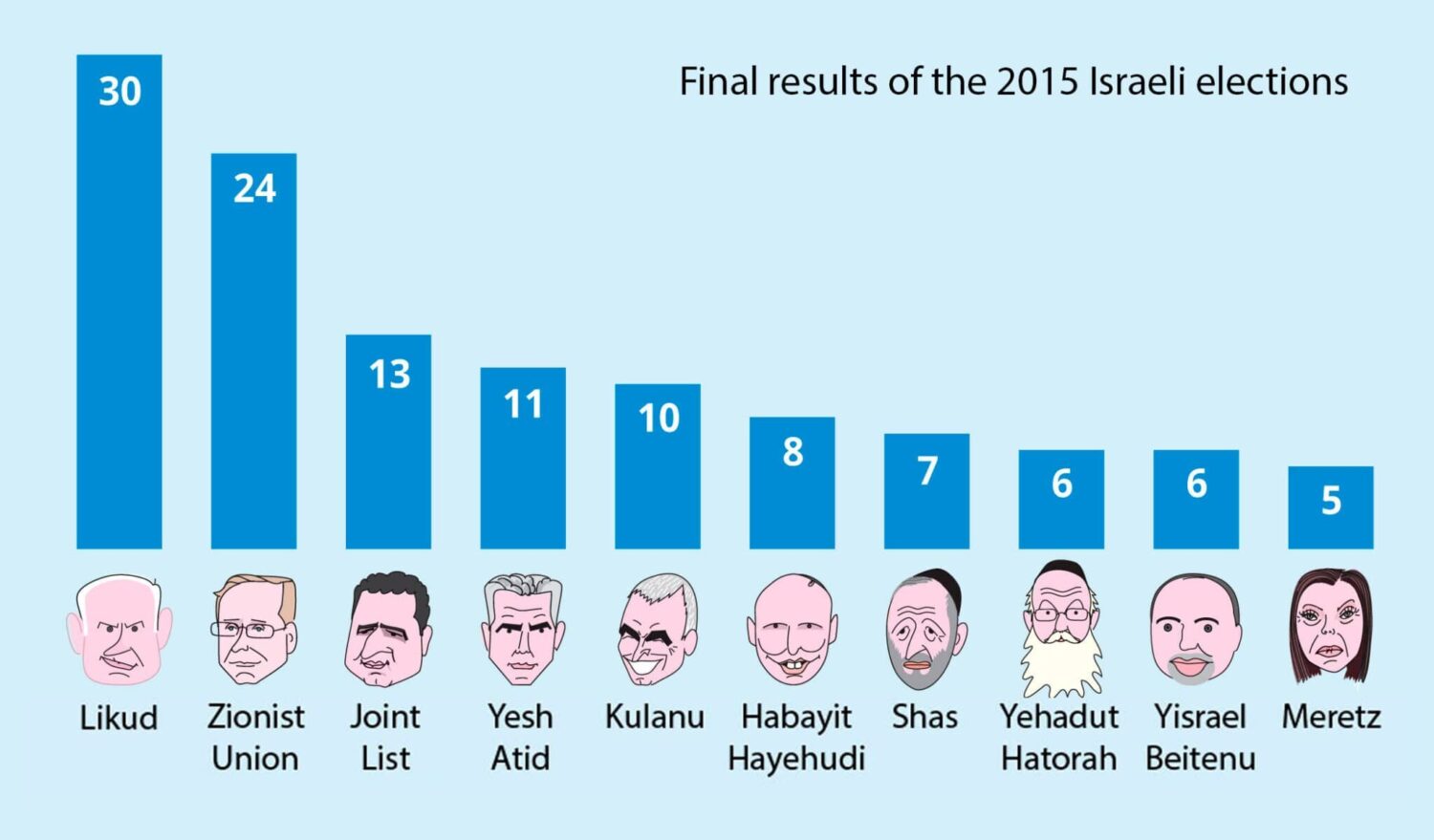

En masse, it seems, voters switched allegiance to Netanyahu’s Likud Party, giving it the edge it needed to cement his fourth term. It is important to note that this was not a shift from left to right but a shift from one right-wing party to another. Even more important is the reason for this behavior. Netanyahu understood the arguments that would motivate his base: not security, not the economy, but an appeal to culture and identity. It is unclear how the Israeli left will respond to this appeal or how – after so many years of failure – it can regain the ground it has lost in the battle of culture and identity.

Meanwhile, while the Jews were splintering into right and left, Israel’s million-plus Arab citizens were mostly uniting. In recent elections, three separate Arab parties – loosely labeled as communist, Arab nationalist, and Islamist – have vied for the Knesset. Those party labels may have been imprecise, but Israel’s Arab public – like its Jewish one – has its fissures and cultural-ideological disagreements. Ahead of this election, though, the Knesset raised the threshold for a party to enter parliament from 2% of the total votes cast to 3.25%. This was motivated by a general desire to rid the system of small parties and encourage more stability in governance. But, spearheaded by right-wing politician Avigdor Liberman, the move was also aimed at raising the threshold high enough that the Arab parties would not attract the required votes and so would be shut out of the Knesset entirely.

In response, the Arab parties agreed to run on a single “Joint List,” and Arab voters responded with jubilation. As a result, representation of the Arab parties in the Knesset rose from 11 seats to 13 on the back of increased voter turnout. The Joint List’s leader, Ayman Odeh, also emerged in the eyes of the Jewish public as a more moderate voice than past Arab party heads. This potentially paves the way for dialogue on easing the discrimination faced by Israel’s Arabs in many walks of life – discrimination acknowledged not only on the left but also by many on the right. Despite their modest gains, however, Arab representatives will continue to be sidelined, victims of “King Bibi’s” ability to mobilize his base.

Elections once thought to be issues-based – whether it was security, the economy, or spending abuse claims at the prime minister’s official residence – were, in the end, not about the issues at all. Instead, this was a vote between two different tribes, one “left” and one “right.” Netanyahu understood that all along.