Introduction

The population of the State of Israel was estimated at 9,291,000 by the end of 2020, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. Jews accounted for 73.9% (6.87 million people) of the total population, while Arabs accounted for 21.1% (1.956 million), and others (non-Arab Christians, other religions, and those not affiliated with any religion) 5%, about 456,000. The gender ratio was estimated at 101 males per 100 females.

During the year 2020 AD, the population growth rate was 1.7%, compared to the number of the population in 2019. 84% of the increase was due to the natural growth of the population, while 16% of it was from the international migration balance (returning citizens and people who migrated under the law of entry).

About 176,000 children were born during the year (73.8% to Jewish mothers, 23.4% to Arab mothers, and 2.8% to other mothers). While about 20,000 new immigrants immigrated to Israel, compared to 34,000 in 2019.

About 50,000 people died in 2020, and one in every 15 deaths was related to the Coronavirus.

It is expected that the population of Israel will continue to grow at a relatively rapid pace during the middle of this century, with the number reaching 15.2 million by 2048 (the centenary of statehood). The Jewish population of Israel is expected to exceed 11 million by then.

Israelis are equally divided between men and women at 50 percent for each sex. 44.3% of the Israeli population classify themselves as secular, while 21.4% consider themselves conservative, 12.3% are conservative with religious leanings, 11.5% are religious, 10.2% are extremist Jews.

The languages spoken are Hebrew (the official language), Arabic (which has a special status under Israeli law), and English (the most widely used foreign language).

Age Groups

In terms of the age structure of the population, the estimates for the year 2020 AD showed that 41.43% of the population is under the age of 25 years, 37.2% falls in the age group (25-54) years, 8.4% is between 55 and 64 years, while 11.96% Of the population 65 years and over.

The fertility rate in Israel in 2020 was 3 births per woman. The year 2018 AD witnessed the fertility rate of Israeli Jewish women exceeding the fertility rate of their Arab peers, for the first time in the country’s history, according to data issued by the Central Bureau of Statistics, and the rate among Jewish women residing in Israel and in Israeli settlements in the West Bank was 3.05 compared to 3.04 for Arab women in Israel. The data excludes Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip who are not Israeli citizens.

The average life expectancy in Israel is one of the highest in the world, as it is estimated at 85.15 years for women, and 81.25 years for men.

Areas of Habitation

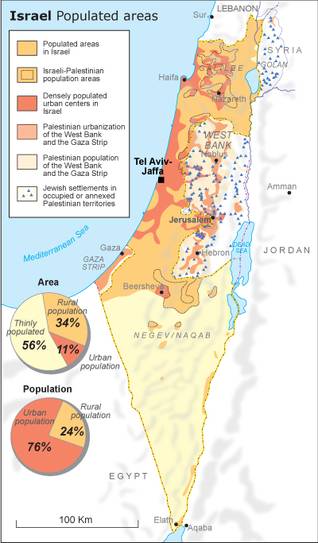

Israel does not have internationally recognized borders, so it is very difficult to determine the density of its population.

Tel Aviv is the country’s financial centre and the second largest city. The Tel Aviv metropolitan area, called Gush Dan, is the largest in the country. In 2020 AD, the five largest cities by population were Jerusalem (936,047), Tel Aviv-Jaffa (461,352), Haifa (285,542), Rishon LeZion (254,238), and Petah Tikva (248,005).

Jerusalem is the capital, although the United Nations does not recognize it, and Israeli sovereignty over Jerusalem is the subject of an ongoing conflict between Palestinians and Israelis.

In 2017, the United States officially recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and transferred its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the largest city in historic Palestine (Israel and Palestine) and one of the oldest cities in the world. It is also a holy city in Judaism, Islam and Christianity.

The State of Israel was established in an area inhabited by the Palestinians. During the 1948-1949 war, about 80% of the Palestinians were expelled or fled by the armed Jewish forces. The Jewish population is made up of diverse communities, including Ashkenazim (Jews from Central, Eastern, and Western Europe), Sephardic (from the Iberian Peninsula and the northern part of the Mediterranean region) and Mizrahi (from the Arab world), as well as other groups.

This largely explains why other languages are used besides Hebrew in Israel, especially English and Russian. Although the first generations of Jewish settlers were mostly secular, the influence of religion on the Jewish community has increased steadily since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. For example, the Haredim community stands out as a religious group in Israeli society; The indigenous Palestinian community – which constitutes 20% of the total population – is either Muslim or Christian.

Historical Palestine

Historical Palestine‘s population has its roots in ancient times when the adoption of agriculture and a better command of water winning techniques enabled the spread of settled village communities, most prominently on the central mountain ridge.

Conditions in the coastal plain, characterized by extensive sands and marshes, were less favourable to intense cultivation, but offered opportunities for the emergence of cities based on maritime trade. The line between what has been described as ‘the desert and the sown’, toward the east and the south, between cultivation and pastoralism, shifted back and forth in drier and wetter periods.

Altogether, these regional ways of life, from the mercantile coast in the west, the agricultural mountainside in the centre and the pastoral fields in the east, presented a continuum in which livelihoods and population numbers were subject to constant change and adaptation.

In times of stability and peace, combined with favourable climatic conditions, population numbers would increase, straining the country’s resources. In times of political turmoil, often related to climatic adversities such as drought, population numbers could drop dramatically. Migration to regions in the vicinity or farther away was a way to adapt to scarcity.

Throughout the centuries, rural agriculture in Palestine was inclined to expand its resource basis to a level of saturation or exhaustion, causing distinct migratory patterns. Migrations occurred from the mountains to the urbanizing coastal plain, where migrants joined the ranks of craftsmen and traders.

People also migrated from the mountains to the east and the south as a result of long spells of drought, compelling farmers to become pastoralists. Perhaps the most substantial movement, however, was migration overseas, in most cases from the coastal plain. This happened in periods when cities became overcrowded or caught up in war, inducing craftsmen and traders to look for a safer haven elsewhere.

Regionalization

The historical evolution of Palestine’s population witnessed a number of cultural and political phases. Palestine’s oldest settled communities formed part of a larger cultural entity known as Canaan. It was dominated by a scattering of small city-kingdoms.

The transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age at the end of the first millennium BCE witnessed the influx of tribes from the north and the east who were settling among the established rural and urban communities, quickly adopting their language and culture.

This period was followed by the rise of regional inland kingdoms, which exerted pressure on the coastal plain. One of these, the kingdom of Aram, centred at Damascus, gained so much importance for the expansion of overland trade that its vernacular replaced the spoken forms of the original Canaanite language.

The closely related Aramaic tongue was used in daily communication and trade. The Canaanite language was preserved as a scriptural language in the sphere of religion (later designated as ‘Ancient Hebrew’).

In this period the designation ‘Canaanite’ gave way to names derived from the regional kingdoms, such as Philistine, Israelite, Judean, Edomite, and Aramean. These identities overlapped the commonly spoken language and cultural customs. At the same time, Canaanite cults evolved or diversified into regional varieties. These, however, continued to share a common reverence for the ancient supreme deity El.

The Roman era

The gradual integration of Palestine within the larger political frameworks of the Hellenistic and Roman empires gave prominence to regional religious affiliations such as Samaritan, Judean, and Christian, which Palestine’s inhabitants began to identify themselves with.

The absorption of Palestine into the Hellenistic-Roman commonwealth spurred a lengthy period of steady economic and demographic growth, although it initially went through a troubled phase when Judean and Samaritan inhabitants who rejected subjugation resisted the changes. This led to a number of violent but failed revolts, that temporarily emaciated the countryside.

Both the trend of accelerating economic growth and the episodic resurrections led to substantial migration. A considerable number of migrants moved to destinations overseas, settling in the Empire’s largest cities. Scriptural records of the time mention the proliferation of ‘Syrians’ and ‘Judeans’ or ‘Hebrews’ in Roman cities which formed congregations that kept on practising their traditional cults.

Throughout most of antiquity, Palestine’s population oscillated from lows of some 300,000 to highs exceeding half a million. But in late antiquity, Palestine’s population continued to grow, eventually surpassing the two million mark.

Late antiquity to early Islamic era

Initially, the cosmopolitan character of the Roman Empire placed few obstacles in the way of religious communities in Palestine to preserve traditional cults, as long as loyalty to the state was guaranteed. This changed after the Roman emperors adopted Christianity as a state religion from the end of the fourth century.

The scope of religious freedom narrowed considerably when Roman Byzantine emperors, such as Heraclius in the 7th century, grew intolerant of traditional beliefs. Through a combination of persecution and coerced conversion the Samaritan and Judean communities began to dwindle, particularly in the country’s urban regions where state authority was strongest.

The Arab conquest

The conquest by Arab Muslims in the seventh century would prove to be a major development in the cultural evolution of the Palestinian population. Incorporation of the country into the Arab empire would leave a lasting imprint. Scriptural records suggest that the country’s inhabitants welcomed the new rulers as a relief from imperial Christian Byzantine oppression.

The caliphate’s attitude was tolerant and pragmatic toward religious minorities, such as Jews, Samaritans and Christians who were viewed as People of the Book (Ahl al-Kitab), which as a scriptural source for Islam was held in high esteem.

Nonetheless substantial numbers of the country’s inhabitants began to adopt Islam, to a large degree because taxation policies were disadvantageous to non-Islamic believers, but also because the step was not seen as too dramatic, particularly for rural believers in the countryside.

Another fundamental landmark was that the Aramaic vernacular was strongly influenced by the vocabulary of the Arabic language of the new rulers. As a result, it developed organically into what is known as colloquial Arabic in a number of dialectal varieties. Palestine’s demographic and cultural foundations had thus largely been established in the Early Middle Ages.

Immigrants

A dramatic decline set in following the fragmentation and collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate from the 10th century, turning Palestine into a bone of contention between rivalling Turkish dynasties. For a considerable period the region became subject to the rule of crusader principalities. Incessant wars and famines reduced the population to about one-fifth of what it had been previously. Conditions stabilized when Palestine became a province of the Mamluk Sultanate. This was the start of a period in which various religious and ethnic communities migrated to Palestine, which was encouraged by most local rulers.

In the 12th century, considerable numbers of the Druze sect settled in the northern mountains. When the Turkish-Ottoman dynasty extended its rule over most of the Arab lands, including Palestine in the 16th century, other migrants arrived from all over the Ottoman Empire, as result of trade relations, pilgrimage, and other cultural and economic contacts.

Ottoman times

Ottoman authorities began to employ units of guards and orderlies recruited for police duties from foreign countries. As a result, a few Cherkez or Circassian communities from the Black Sea region settled in the country’s north and communities of black Africans came to the Jordan Valley and the city of Jerusalem. The Turkish authorities also encouraged Jewish immigration, initially mainly of Ladino speaking communities who had found refuge in the Ottoman Empire from persecution by Spanish and Portugese monarchs especially in the 15th century. Most settled in Jerusalem, the spiritual Judaic centre.

Additional communities found residence in the cities of Gaza, Tiberias, Safed, Nablus and Hebron. In the 17th and 18th centuries their numbers were reinforced by Jews from Eastern Europe, also fleeing oppression, and from lands in Central Asia. Palestine’s Jewish population continued to speak in the original mother tongues of Ladino and Yiddish, but became generally conversant in Arabic as well. The distinction between Sephardic Jews (from Hebrew Sefarad, meaning France) and Ashkenazi Jews (from Hebrew Ashkenaz, meaning Germany) dates from this period.

Developments in the late 19th century reversed the decline and stagnation of the previous centuries. The rise of European powers renewed interest in the Levant. It brought governments, religious institutions and mercantile associations to offer patronage to non-Islamic denominations as a way to regain a foothold in the Orient.

External Support

European patronage in Palestine took peculiar forms that included the foundation of hospices, infirmaries and schools, but also of communal settlements within cities and in rural areas. The walled city of Jerusalem became surrounded by sizeable Christian compounds of inhabitants from France, Great Britain, Russia and Germany competing with one another for social and political influence.

The late 19th century witnessed a rise in European nationalistic fervour, which brought nations to create overseas dominions in lands thought to be without orderly, civilized rule. Such views also prevailed within the World Zionist Organization, a movement of European Jews taking inspiration from the tenets of national emancipation based on the idea that Jews constituted a religious ethnicity entitled to a separate, own nationhood.

Realization of this vision would require a national territory populated by Jews who would till the earth and work in factories, instead of just being pious worshippers.

The Zionist view of a distinct religious-ethnic nationalism clashed with that of the indigenous Palestinians who demanded national self-determination for the whole population, without regard of religion. From the mid-19th century, wealthy and influential European Jewish patrons began supporting Palestinian Jews with institutions, subsidies and funds to establish settlements.

Social and economic deprivation and incessant persecutions in Eastern Europe compelled large numbers of Jews to emigrate, most of them to America, but also to Palestine. Within two decades, the number of Palestinian Jews had doubled to around 70,000 at the time of World War I. These made up about 10 percent of the country’s population.

Most Jewish immigrants settled in the cities of Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, where scant sources of livelihood were available. Zionist leaders, keen to strike Jewish territorial roots, made efforts to buy up lands around the cities in order to establish rural Jewish settlements. In most cases, opportunities to buy lands were limited to marginal holdings of Arab notables, which were unprofitable to cultivate without substantial investments in drainage or irrigation.

It restricted Jewish colonization mainly to the country’s low-lying plains, which were often marshy and malaria infested. It took immense efforts by Jewish rural pioneers to turn these into profitable lands. Despite these efforts and investments, the scope of acquired Jewish land before the proclamation of the State of Israel never exceeded 7 percent of the total territory. More than two-thirds of the Jewish population remained concentrated in Palestine’s three largest cities.

Nonetheless, the demographic and territorial foundations for Jewish nationhood in the country, although extremely tenuous, appeared to have been laid on the eve of World War I. As a result of Jewish immigration, Palestinian cities grew sizeable suburbs which could equal or even exceed the original city, as in Jerusalem and Jaffa, which was eventually turned into the separate Jewish municipality of Tel Aviv.

Three distinct clusters of Jewish rural settlements also emerged in the plains around the cities of Jaffa, Haifa, Tiberias and Safed, which were gradually merging. A pattern became visible in which the distinction between the plains and mountains would also mark areas dominated by either the Jewish or the Palestinian population.

Demographic Upheaval

The outcome of World War I, as a result of which Western colonial powers replaced Turkish rule over large parts of Arabia, would lay the basis for dramatic geopolitical developments. Despite initial promises of Arab sovereignty, Great Britain secured a governmental mandate over Palestine that incorporated a promise of a wholly different nature, expressing support for ‘a national home in Palestine for the Jewish people’.

British foreign rule left Palestinian society vulnerable to the objectives and effects of ensuing large-scale Jewish immigration. Within three decades, the number of Jewish inhabitants would expand sixfold, making up about a third of the country’s population. However, Jewish land acquisition did not keep in step, remaining four times smaller in proportion to population growth.

Although perceived as a principal threat by Palestinians, the less than modest territorial Jewish foothold, stretching in patches across the country’s northern plains and interspersed with numerous Palestinian towns and villages, looked critically short of meeting conditions for obtaining actual statehood.

Except in the eyes of Zionist leaders and pioneers who believed that even the tiniest territorial base could gather adequate momentum to turn the scales in favour of sustainable Jewish independence. Viewed in terms of removing obstacles, the resolve and capacity of Palestinians to stand up for their national rights fell dramatically short of what the Jewish community could muster.

The absence of effective public Arab agencies, in combination with an internally divided, conservative, feudal and parochial leadership, placed the Palestinian society at a distinct disadvantage in the face of colonial rule and the Zionist enterprise.

Mounting tensions exploded leading to violent hostilities in 1947, when United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181 recommended to allocate more than half the country for a Jewish state, despite its population’s minority position and its minimal hold of land (see further UNGA Resolution 181).

When the State of Israel was proclaimed the next year, Arab neighbour states intervened in defence of Palestine, but barely succeeded to hold ground in the country’s remoter districts (see the War of 1948-1949).

The advance of Israeli armed forces and its deliberate use of violence against civilian targets, caused the flight of about 80 percent of the Palestinian population in 1948 and early 1949, predominantly from the country’s plains to the mountainous interior and to an area in the coastal strip, held by Egyptian troops (see also the Nakba). Many Palestinian refugees fled even further across the borders to find a temporary safe haven elsewhere, mainly to the West Bank (in 1948 occupied by Jordan), the Gaza Strip (since 1948 under the control of Egypt), Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria.

In 1949, a ceasefire was enforced, producing armistice lines that left Israel in control of more than three quarters of the country. Although the guns had fallen silent, Israel and the Arab states remained in a state of war, freezing the positions of the opposing armed forces. As a result, Israel was able to continue to ignore United Nations Resolution 194, which called for Israel to enable the immediate return of the Palestinian refugees.

However, since the Jewish demographic predominance in the newly created State of Israel had been the result of deliberate expulsion of Palestinians, this was never seriously contemplated anyway.

Palestinian Fragmentation

In the 1950s, an entire new situation had emerged with a dramatic upheaval of the country’s original demographic and political characteristics. The name Palestine had disappeared from the map to make room for that of Israel. The original Palestinian population lost preponderance. Palestine’s habitat also lost its geographic cohesion and socio-economic centre along the coast. The country’s major plains had been ‘de-Palestinized’, except for the tiny section of the Gaza Strip, as a result of the massive flight of indigenous communities to safety elsewhere.

The newly created demographic ‘vacuum’ was immediately filled by an equally substantial wave of new Jewish migrants. In the years after the armistice, Israel demolished over five hundred abandoned Palestinian localities and established new Jewish settlements in their place. The arrival of new immigrants doubled Israel’s Jewish population to 1.2 million in 1950, equal to the number of Palestinians only two years earlier. As about half of the Palestinian refugees had fled the country, the number that remained fell below that of the Israeli-Jewish population, almost reversing the initial equation of the population, of whom two-thirds had been Palestinian and one-third Jewish.

Of more far-reaching consequences was the break-up of Palestine’s geographic cohesion. It became segmented into four separate fragments. First, there was Galilee in the north, where roughly 150,000 Palestinians remained under Israeli military rule. Second, the largest fragment was made up of the mountainous interior, which became known as the West Bank after it was annexed by the Kingdom of Jordan, which now possessed both banks of the river after which it was named. The influx of refugees had doubled the West Bank’s Palestinian population to over half a million of whom substantial numbers resettled in the Jordan East Bank.

Another fragment was created when Israel encroached upon the adjacent area of the Negev desert, inhabited by Bedouin tribes, many of whom wandered to quieter places awaiting the restoration of calm before returning to their traditional pasturages. However, Israel started to drive out remaining tribes and concentrated others in the so-called Ezor HaSayigh (Mintaqat al-Siyaj), a territorial enclosure resembling an ethnic reservation around the originally Palestinian town of Bir al-Sab, renamed Be’er Sheva (Beersheba).

The last fragment, situated in what became known as the Gaza Strip, represented the ultimate level of Palestinian deprivation. Most of the originally large district, counting numerous productive villages, had fallen into Israeli hands. More than 150,000 refugees had to be accommodated in the narrow confines of the strip which was administered by Egypt.

The four Palestinian fragments, scattered across the country’s periphery, sharply revealed what had been lost in the centre. The coastal plain had functioned as a motor for Palestine’s socio-economic and cultural development. Adjacent to the Jewish city of Tel Aviv, the cities of Jaffa and Haifa were growing into dynamic centres of commerce and industry, functioning as maritime gateways to overseas markets. In these urban environments Arab printing houses, cultural and educational institutions multiplied, giving impetus to the modernization and liberalization of Palestinian society.

Israeli dilemmas

The territorial imperative of Jewish nationalism to turn Palestine into Israel stumbled over the native Palestinian population. The War of 1948-1949 had emptied the country’s plains of its Palestinian inhabitants. Israel’s first effort was to ensure that the emptied places were inhabited by Jewish citizens, scores of whom were willing as many new immigrants were in need of subsidized residences.

Nonetheless, there was growing concern in Israel about the discrepancy between the state’s demographic configuration and its factual borders that enclosed sizeable Palestinian minorities adjacent to the West Bank and Gaza Strip, held by Jordan and Egypt. From a geographic perspective it would not be difficult to re-attach these to the Palestinian areas not conquered by Israel. Although politically disabled, the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947 could still be realized demographically. Israel resorted to a variety of measures to avoid such a scenario. One was to demolish most of the abandoned Palestinian localities within the plains, which would keep these regions securely within the Jewish state.

Determined to hold on to the conquered Palestinian areas that had been allotted to the intended Palestinian state, Israel granted Israeli citizenship to its Palestinian inhabitants. As a minority they would not jeopardize the state’s Jewish character. Through this step Israel’s claim to the conquered areas beyond the Partition Plan’s outlines was thought to become irrefutable.

One problem still remained, which was related to the difficulty of settling Israeli Jews within areas populated entirely by Palestinians, regardless of whether these were official Israeli citizens or not. In answer, Israel pursued a phased settling strategy that began with the encapsulation of Palestinian population areas, followed by their territorial and demographic break-up, effectuated by what was called ‘fragmentation’. Both processes would be based on substantial expropriation of Palestinian village lands, in particular of communal holdings that presented the least judicial obstacles. These lands would then be settled by Jews, or if failing to attract adequate numbers, be turned into forest or nature reserves, declared out of bounds for agriculture or herding.

Encapsulation

The first phase of encapsulation was largely completed in the two decades running up to 1967. By then, the Palestinian Galilee had been enclosed by new Jewish settlements, almost completely isolating it from the sea. There remained a fragile corridor to the originally Arab port city of Acre, which became a so-called mixed city when it in turn was encapsulated by Jewish suburbs. In the same process the Galilee also became isolated from adjacent Arab areas in Lebanon and the Jordanian held West Bank. A similar pattern of encapsulation ensued in the Negev Desert through the foundation of so-called Jewish ‘development towns’, which encircled the Ezor HaSayigh, the reservation where the region’s Bedouin tribes were being concentrated.

The June War of 1967 extended Israeli rule over all of Palestine. It rekindled the same geopolitical debates that arose following the conquests two decades earlier. The atmosphere after June 1967 was one of Israeli euphoria, coupled with Palestinian shock and despair. Postcards were printed showing the contours of what was called ‘Greater Israel’, stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River, flanked by the additionally conquered territories of the Syrian Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai Desert. The spontaneous, almost irresistible impulse was to settle the conquered territories and to realize the fundamentally Zionist vision of Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel, Greater Israel).

However, the governing Labour coalition was harbouring second thoughts. Incorporation of the West Bank would mean another 600,000 Palestinian citizens in addition to the roughly 300,000 Galilean Palestinians who held Israeli citizenship. As a result, the proportion of Palestinians within Israel would increase to close to one-third of the total population. Absorbing the Gaza Strip would bring their number close to 40 percent. Moreover, the high birth rate among Palestinian women could even lead to an outright majority in just two or three decades, which would entirely jeopardize the character of Israel as a Jewish state.

This consideration brought Israeli cabinet minister Yigal Allon to conceptualize a plan that advocated restricting Jewish settlements to thinly inhabited strips of land which would encapsulate Palestinian population areas. The Allon Plan made one notable exception to this guideline. Arab East Jerusalem and its surroundings were incorporated within the substantially expanded municipality of the Israeli capital – which is not recognized as such by the international community –, providing ample space for the construction of a belt of Jewish settlements that would isolate the city from its West Bank hinterland.

Israel then proceeded to establish a string of settlements in the Jordan Valley, that in turn isolated all of the West Bank from the Jordan East Bank across the river. In this way the Allon Plan completed the full encapsulation of all remaining Palestinian territorial fragments, including the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, that Israel did not want to incorporate politically or demographically.

Jewish Settlers

The victory of the Likud coalition in the 1977 elections initiated a landmark divergence from the Allon Plan. Spurred by the vision of ‘Greater Israel’, embraced in governmental circles and settler organizations, the World Zionist Organization drafted a new grand settlement plan that would turn this vision into solid reality. This ‘Plan for the Development of Samaria and Judea’ (Hebrew names for the West Bank) stipulated the colonization of the mountainous interior with clusters of rural and urban settlements, envisioning an increase in the Jewish population from 800,000 up to 1 million. The clusters of settlements were meant to fragment, disintegrate and render subordinate the largest remaining Palestinian territory, beneath a patchwork of new Jewish cities and industrial parks, interconnected by means of a network of separate so-called ‘bypass’ highways.

The plan appears to have drawn inspiration from similar plans that were being implemented in the Galilee and the Negev. These were based on large-scale expropriations of Palestinian communal lands, most of which were incorporated by newly established Jewish settlements. Such plans reinforced processes through which Palestinians in these areas were being cut off from their traditional agricultural sources of livelihood, transforming them into a class of predominantly menial workers.

However, this policy of Jewish settlement of the Galilee had mixed results. On the one hand it antagonized large portions of the Palestinian population who accused the state of discriminatory policies regarding development planning, provision of civil services and allocation of public funds. On the other hand only modest numbers of Jewish citizens were drawn to the new, remote settlements, despite enormous investments in infrastructure. Although considerably fractured, the Galilee still remains demographically dominated by its Palestinian inhabitants.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Population’ and ‘Israel’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: