Introduction

Although modern-day Israel was only formed in 1948, the emergence of Hebrew newspapers in the region go back almost a century before that. In 1863, prominent Jewish businessmen established the first Hebrew publication, Halevanon, in Jerusalem, followed by Havazzelet six months later. The Ottoman leadership subsequently shut down both publications, but Havazzelet reopened in 1870 and continued as a weekly newspaper until 1911. The first Hebrew daily, Haheruth, opened in 1908 but had ceased publication by the end of WWI.

Before and during the British Mandate of Palestine (1920-1948), several print and broadcast developments occurred that would form the basis of the modern Israeli mass media. Daily newspapers with an ardent political and social agenda began to emerge, such as the liberal, pro-Zionist Haaretz in 1919, the labour and trade union-focused Davar in 1925 and the right-wing, Zionist Haboker in 1935.

These publications were restricted by British authorities to 24 pages per week, or four per day. The first Zionist radio broadcast transmission took place in 1932, but regular programming only became possible with the establishment of the Palestinian Broadcast Service in 1936. The British authorities initially saw radio broadcasting as a means of easing rising tensions between Zionist settlers and Palestinians, but the Hebrew broadcasts were often explicitly nationalistic and inflammatory.

Following the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, a previously underground Hagenah radio station broadcasting out of Tel Aviv was renamed Kol Yisrael and established as the country’s public radio service. Emergency regulations, enacted by the British authorities in 1945, were incorporated into Israeli legislation, granting the state powers to censor published content and close down media outlets.

Although entirely privately owned, the Israeli press was largely supportive of the government and remained so until the 1980s, when regional events sparked an upsurge in domestic criticism.

Television broadcasts began in Israel in 1966 and continued to air in black and white until the beginning of the 1980s. For nearly 25 years, Israel had only one television channel, which was state owned, but multichannel programming was introduced in the early 1990s in response to the country’s plethora of illegal cable TV networks and private satellite dishes. In 1990, the state created the Second Israeli Broadcasting Authority, with the remit to license and regulate newly established private television and radio outlets.

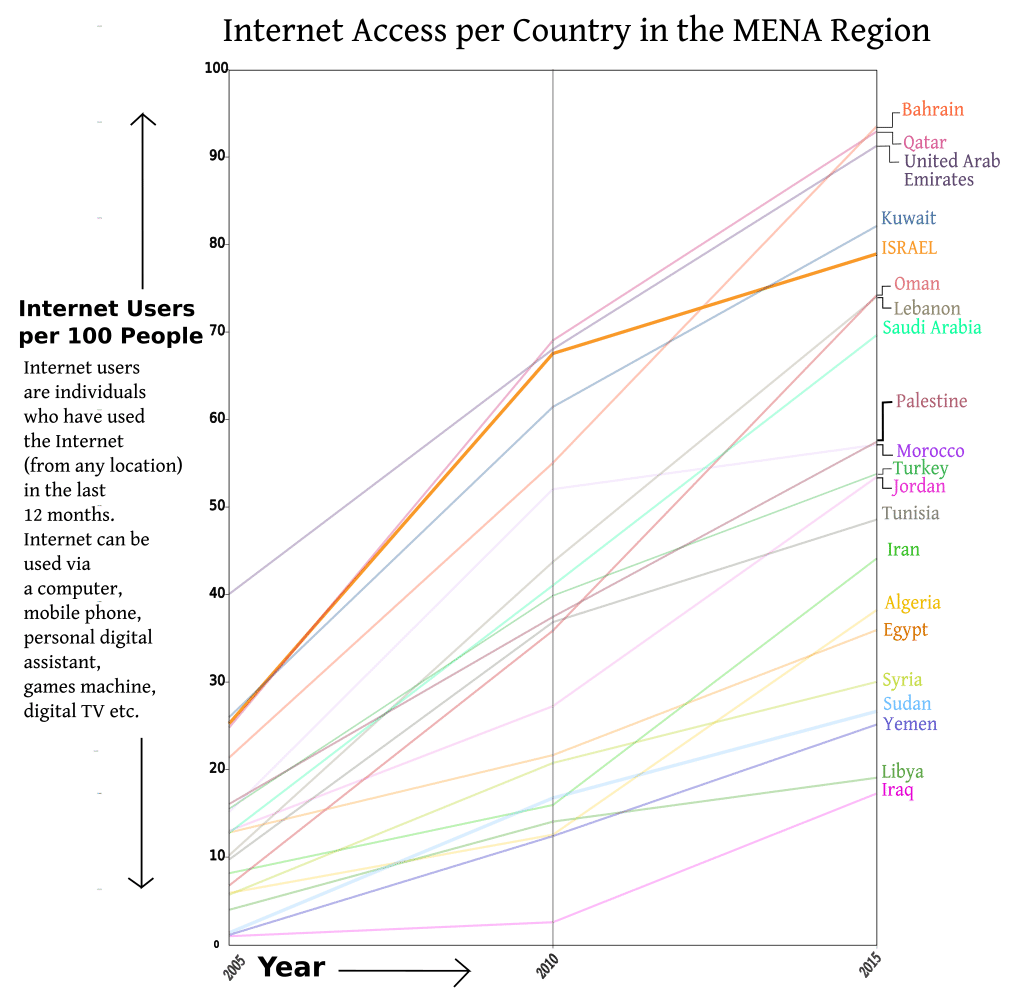

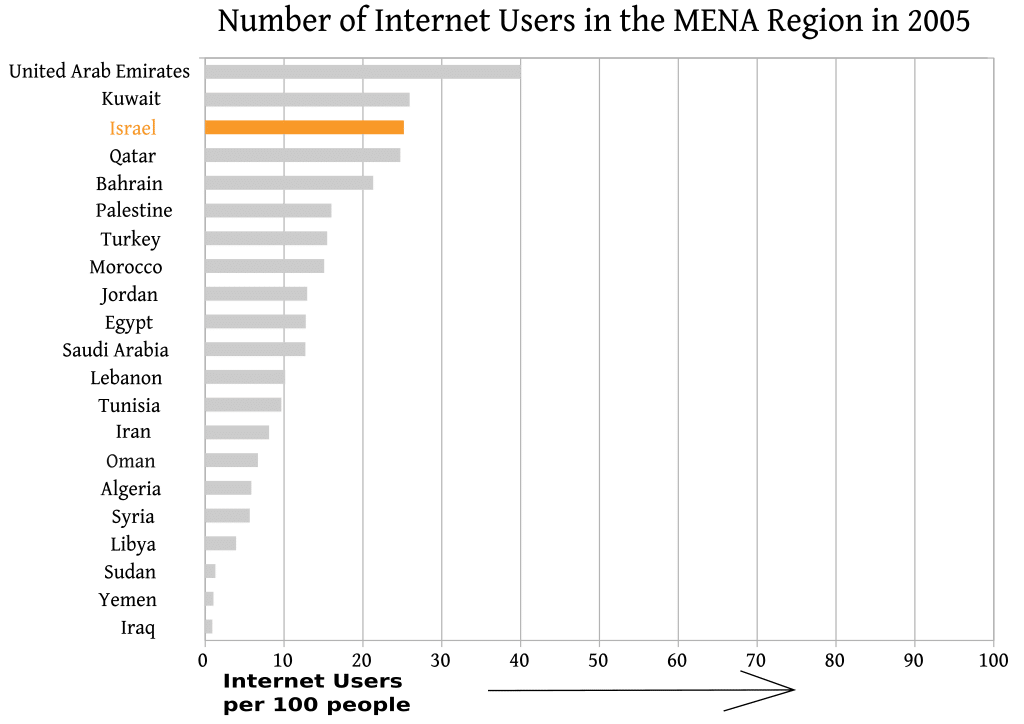

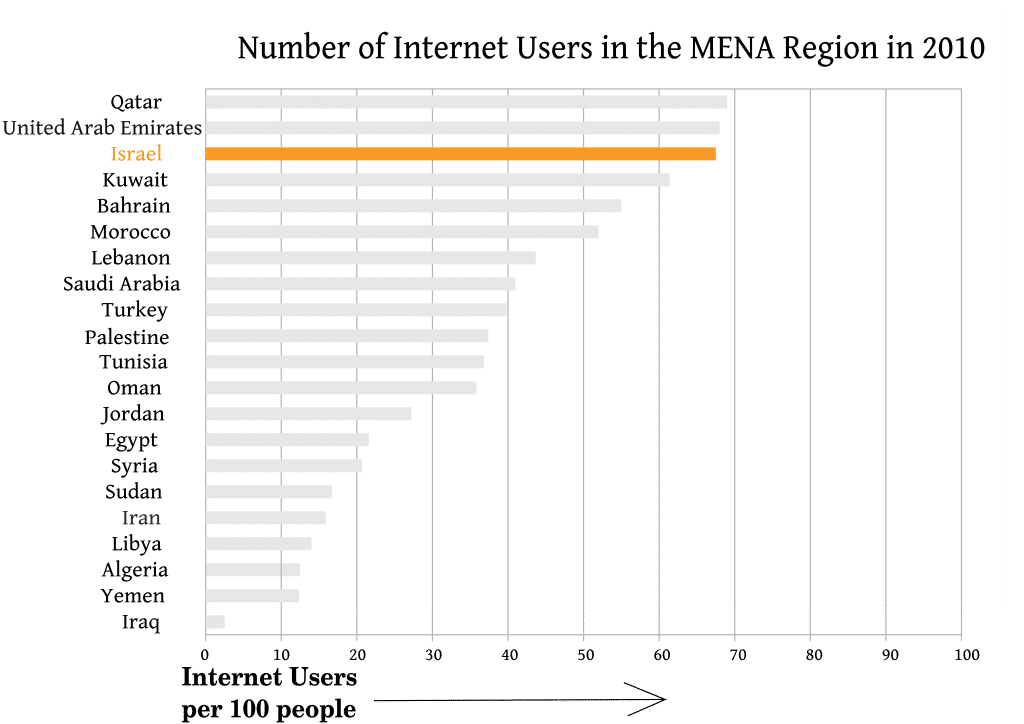

Israel was one of the first countries in the world to embrace the internet, with the.il country code domain name being the third registered in 1985 after the United Stated and United Kingdom. Academic institutions had internet access as of 1990, while in 1994 private individuals could obtain home access with the establishment of three Israeli internet service providers.

Israel’s 21st-century media landscape is relatively free and pluralistic by regional standards. However, emergency regulations remain in place, granting the Israeli army the power to enact military censorship and impose press injunctions on certain information. Ongoing conflict and tensions with the Palestine territories have also led to heightened security measures at the expense of media freedom.

The media environment is also evolving due to economic pressures. In 2014, the Knesset (parliament) approved a bill to replace the financially unstable state broadcaster, the Israeli Broadcasting Authority (IBA), with a new corporation that would purportedly enjoy greater exemption from government oversight and less direct intervention from politicians. However, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has since been a vocal opponent of the bill and the new broadcaster’s proposed powers, and in March 2017 threatened to dissolve parliament unless the reforms were cancelled.

Freedom of Expression

Israel ranks 101st in Reporters Without Borders’ 2016 World Press Freedom Index. The country’s Basic Laws serve as its constitutional foundation, and although specific Basic Law legislation addressing freedom of expression and association has been proposed, it has yet to be approved by the Knesset.

Nevertheless, human rights watchdog Freedom House observes that Israel’s legal environment and Supreme Court is ‘predominantly protective of media freedom’, with court recognition of journalistic privilege and freedom of information. There are several exceptions, however, including the emergency regulations outlawing hate speech and incitement to violence that are occasionally subjectively applied to media outlets. In 2012, Israel also passed a bill outlawing domestic calls for boycotts of Israeli products.

Press regulation requirements provide the Israeli state with an additional level of control over press and broadcast content. Israeli publishers require a licence from the Interior Ministry to establish a newspaper, while the Government Press Office (GPO) stipulates that all journalists operating in the country require accreditation, which has occasionally been refused for national security reasons.

The Israeli army can also shut down any media outlet for national security reasons, although this power has been curbed by a 1996 censorship agreement between the Israeli army and the press. Finally, from 2015 onwards, Netanyahu also served as head of the Communications Ministry, allowing him to regulate the Israeli broadcast market. In February 2017, he announced he would relinquish this responsibility.

Israel also holds a high number of Palestinian journalists in custody under its emergency regulations. The Palestinian Journalists’ Union alleged in 2016 that 19 Palestinian journalists were being held in administrative detention, and that one had been held for more than 20 years. In January 2017, a further journalist, Muhammad al-Kiq, was arrested by Israeli security forces following a demonstration in Ramallah in the West Bank. Al-Kiq was detained without charge and subsequently went on hunger strike, which ended in March after Israel agreed to his release the following month. Al-Kiq had previously been arrested by Israeli authorities a year earlier, and was released in May 2016, following a three-month hunger strike.

At particularly heightened times of Israeli-Palestinian tension, foreign media outlets have complained of a hostile working atmosphere. Covering the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict, journalists from the BBC, CNN, and al-Jazeera reported physical and psychological intimidation by the Israeli authorities.

At present, Israel’s online media environment is relatively open, but in 2016, the Justice Ministry began drafting legislation that would enable the authorities to remove social media posts deemed to incite terrorism. The legislation still requires parliamentary approval, but if passed it would theoretically afford Israel a widespread online censorship and surveillance remit.

Television

The most notable television channels in Israel are as follows:

State-owned

Channel 1 – Israel’s first television channel, established in 1968. It aired its daily flagship news bulletin, Mabat, in English and Hebrew until 2014, when the English broadcast was stopped. Ninety minutes of Arabic-language broadcasts were also aired daily until 2002.

Channel 33 – Founded in 1994, initially as an Arabic-language channel targeting foreign viewers. Since 2002, it has also served as the primary news and entertainment channel for Arabic-speaking Israelis.

Private

Israeli channel 2. Photo Flickr Channel 2 – Launched in 1993 with a joint contract tender between private broadcasters Reshet and Keshet Media Group, with each company broadcasting content for three to four days per week, alternating every two years. A 2012 ratings survey concluded that Channel 2 was the most viewed domestic channel, but also found that Keshet’s output was considerably more popular among audiences.

Israeli channel 10. Photo Flickr Channel 10 – Established in 2002 and airing a variety of news, current affairs and entertainment content. The channel drew the ire of the prime minister after investigative journalist Raviv Drucker aired a series of reports in 2008, which alleged that he had contravened Knesset Ethics Committee rules with his foreign travel arrangements. In his capacity as communications minister, Netanyahu pursued the channel over unpaid debts, and in recent years it has suffered both financially and in terms of ratings. In 2015, RGE Media Group became the majority stakeholder and secured the channel’s future.

Radio

Radio remains a popular news and entertainment medium in Israel and an environment in which there is strong competition among public, commercial and private radio outlets. Some of the most significant stations include:

Kol Yisrael – The collective name for the Israeli state radio network. It operates nine radio stations including the flagship Reshet Aleph, along with the news and talk radio Reshet Bet, and the culture and heritage-focused Moreshet. Reshet Gimmel, 88 FM and Kol Ha-Musika are all dedicated music stations, while Reshet Dalet and Reka cater for Arabic and predominantly Russian listeners, respectively. Finally, IBA International is an Israeli world service station aimed at international listeners.

Army Radio – The Israeli army operates two highly popular radio stations in Israel. Galey Tzahal, founded in 1950, broadcasts a variety of news, talk shows and military and educational content. It features Razi Barkai, a prominent Israeli radio journalist. Galgalatz is an offshoot that predominantly airs Western and Middle Eastern music and is popular among younger listeners.

Radio Arutz Sheva. Photo Flickr Arutz Sheva – Zionist radio station established in 1988 as a pirate network broadcasting from a ship in the Mediterranean. It was the only major news outlet to openly reject the 1993 Oslo Accords and was subsequently denied a broadcasting licence by the Israeli government in 1994. Today, the station broadcasts online 24 hours per day in English and Russian.

Kol Chai – Commercial station established in 1996. It mostly airs religious and news content focusing on the Orthodox Jewish community and does not broadcast on Saturdays.

Press

As with elsewhere around the world, the Israeli print newspaper market is declining in popularity. However, it remains an important source of news and is home to some of the country’s oldest media outlets. All Israeli newspapers are privately owned. The most popular are:

Yedioth Ahronoth – Founded in 1936 and published as a tabloid daily that has since gone on to become Israel’s largest newspaper in terms of sales and circulation, although it has recently been surpassed by Israel Hayoum. It is owned by the Yedioth Media Group, which also has stakes in other leading newspapers and has been accused of monopolizing the Israeli print sector. The 2015 Israeli elections were characterized by partisan coverage and something of a media war between the pro-Netanyahu Israel Hayoum and Yedioth Ahronoth, which was critical of the PM.

Haaretz – Founded in 1919, Haaretz is the oldest active daily publication in Israel. It publishes a considerable number of editorials and opinion pieces. It has a political slant to the left of Israel’s other major newspapers, with a secular tone.

Jerusalem Post –Israel’s most prominent English-language daily was first published in 1932 and continued for many years as a left-leaning newspaper. Changes of ownership in 1989 and 2004 signalled a shift in editorial slant, with the publication becoming more conservative on issues such as security and Palestine.

Kul al-Arab – Founded in Nazareth in 1988 as an Arabic-language, Christian weekly publication. Kul al-Arab is staunchly critical of Israel and US policies regarding Palestine and is also circulated throughout the West Bank.

Israel Hayoum – Launched in 2007 as a free daily newspaper. In 2010, it became the country’s most-read newspaper and its market share continues to grow. It is owned by American businessman Sheldon Adelson who is a vocal supporter of Netanyahu. The newspaper’s coverage has been deemed so favourable to Netanyahu that it has colloquially been labelled ‘Bibiton’ (meaning ‘Bibi Netanyahu’s newspaper’).

Online Publications

As print newspapers face declining circulation and revenue, online publications continue to emerge in Israel. A selection of the most notable websites includes:

Ynet – Established in 2000 as the online outlet for Yedioth Ahronoth’s content. However, the platform has since expanded to produce mostly original, exclusive content. It publishes in Hebrew and in 2004, launched an English-language version, Ynetnews.

Nana 10 – Launched as Channel 10’s website in 1999, the website now serves as an online news portal in its own right, with forums for Israelis to discuss political and cultural issues.

+972 Magazine – Established in 2010 as a blog for Israeli and Palestinian writers seeking to provide in-depth accounts of the ongoing conflict and situation on the ground. The name is derived from the shared country dialling code for Israel and the Palestinian territories.

Times of Israel – News website launched in 2012 by David Horovitz, former editor-in-chief of the Jerusalem Post. The website offers content in English, French, Arabic, Chinese and Farsi. In 2017, the site claimed it attracted 3.5 million unique monthly visitors.

Kikar HaShabbat – Founded in 2009 as a Hebrew-language news website targeting Israel’s Haredi Jewish community. The strongly conservative website gained international notoriety in 2015 when it airbrushed US celebrity Kim Kardashian out of photos because she clashed with Orthodox values.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Israel’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Media

With its relatively high internet penetration, Israel has a vibrant social media community. Social networks, particularly at times of heightened unrest between Israel and Palestine, can become heated with passionate and inflammatory posts from citizens and public figures alike.

In 2013, Facebook estimated that it had 4 million Israeli users, 60 per cent of whom use the network on a daily basis. However, the website has been the subject of controversy as many citizens have voiced concerns about the number of Facebook pages inciting violence against Jews and Israelis, prompting the vandalization of Facebook’s Tel Aviv headquarters in 2015. The network has also been used as a discriminatory platform by Israelis themselves, with Avigdor Lieberman, then foreign minister, using his Facebook page in 2014 to call for a boycott of Arab-owned businesses in Israel that had expressed solidarity with the people of Gaza.

Twitter is significantly less popular in Israel, with 2013 estimates suggesting there were only 150,000 registered Israeli users. However, it remains an important source of news in the country and as such is closely monitored by the authorities. In 2016, Twitter agreed to block a tweet, sent from a US-based account, from Israeli IP addresses because it contained information about an alleged sexual assault by a senior figure in the Israeli Justice Ministry. The story had been subject to a government gag order.

In October 2015, the Israeli Foreign Ministry wrote to YouTube asking for the social network to take down several videos that it considered to be encouraging Palestinian attacks. The following month, Tzipi Hotovely, the deputy foreign minister, met with representatives from YouTube and Google to discuss mechanisms to prevent the publication of ‘inflammatory material’ originating in the Palestinian territories.