Introduction

UAE society has one of the highest living standards due mainly to its vast oil wealth, small population, and welfare system. The UAE citizens receive many privileges and benefits from their federal and local governments, including free higher education and social security. Emiratis are thus well-educated and mostly urban.

The UAE’s citizens constitute roughly 19 percent of UAE society; the remainder (approximately 81 percent) are expatriate foreigners of approximately 200 different nationalities. The largest single groups are South and South-East Asians, especially Indians, who make up about 60 percent of the total population. As temporary or long-term foreign residents, expatriates are ineligible for state benefits, and their standard of living can vary considerably, according to their employment and income. At the top of the expatriate salary scale, Western employees can expect to be paid handsomely, while laborers and construction workers are paid meager wages and receive fewer benefits.

The social and economic status of these workers is defined by harsh working and living conditions. While national Emiratis occupy many government and public sector positions, expatriates (except for some top management positions) occupy most of the other positions in the economy. The UAE government is trying to reduce this dependency on foreign labor by encouraging the gradual nationalization (called Emiratization) of certain jobs. Also, expatriates (with few exceptions) are not allowed to start or own a business unless they have a national Emirati partner.

Outside the workplace, the interaction between these segments of society is minimal. Each group leads a mostly insular existence, living in secluded labor camps, apartment towers, gated communities, or exclusive residential areas. Differences in culture, language, religion, and social status tend to divide and even alienate various classes or sections of society into distinct communities reflecting the national or ethnic origins of these populations. One of the most marginalized groups is the Bedouins, long-time residents who had never been naturalized in the UAE.

Civil Society

The UAE has few civil-society organizations. Neither citizens nor expatriates are allowed to form advocacy groups or political parties. UAE citizens are supposed to express their concerns directly to the leadership through traditional consultative mechanisms, such as the traditional open majlis held by many UAE leaders. Still, freedom of assembly is forbidden by law. In some cases, small, peaceful demonstrations of foreign workers on working conditions and other labor issues have been tolerated, but they were dispersed by force in other cases. Foreign laborers working on the large, ambitious construction projects in Dubai have struck to protest poor working conditions and non-payment of wages. Some of these concerns have been addressed by the Labour Ministry’s recent penalizing of employers.

NGOs are usually known in the UAE as associations or societies for public welfare. Although the sector is small, it includes several wealthy philanthropic organizations, some of which operate internationally. There are an estimated 120 public welfare societies in the country. These groups’ work is regulated by the Ministry of Labour and the Department of Islamic Affairs and Charitable Activities. One exception is the International Humanitarian City (IHC) in Dubai, which has several international NGOs among its membership. These organizations are exempted from registering with the authorities unless they plan to fundraise or work in the UAE. The IHC was set up as a free zone by royal decree in 2007.

Emiratization

The UAE government works through various agencies to train the local Emirati labour force in certain jobs and encourage educated and qualified citizens to enter the workforce. In addition to several ministries that are involved in Emiratization, one agency, The National Human Resources and Development Authority (Tanmia), has as its mission the full employment of national human resources, reducing the foreign component of the UAE labor force and increasing the supply of qualified and skilled national labor. Tanmia is also supposed to support small-investment enterprises through the establishment of self-employment projects for nationals, develop programs for training and qualifying national job seekers, provide career counseling and guidance to the national workforce, and follow up and evaluate employment of nationals in the public and private sectors, among other ambitious goals.

The reality, however, is that the expatriate labor force represents about 85 percent of the UAE’s workforce. These are all temporary guest workers who spend much of their earnings home (as much as USD 22 billion in 2006) and generally return to their countries at the end of their work contracts. This situation will continue because of the chronic need for labor. The UAE is still a favorite destination for job seekers elsewhere in the Gulf region, even after the 2008 financial crisis.

Social Welfare

According to the 2011 Human Development Report, the UAE ranked first in the region and 30th in the world on the Human Development Index. The country was rated one of only two countries in the region in ‘most advanced’ and ‘very high human development.

In 1999 the Federal National Council approved legislation providing monthly social-security benefits to national widows and divorced women, the disabled, the aged, orphans, single daughters, married students, relatives of jailed dependents, estranged wives, and insolvents. Also eligible are widowed and divorced national women previously married to foreigners and expatriate husbands of UAE national women. In 2003 the government distributed approximately USD 179 million to 77,000 beneficiaries of social welfare, the largest group of recipients (12,000) being the elderly. In October 2005, welfare payments to UAE nationals, including the unemployed, increased by 75 percent. The recipient population has dropped since 1980, but the government’s per capita cost has risen by 16 percent. Social-security entitlements constitute 1-2 percent of gross domestic product.

Federal government investments and services were reported to be 58 percent of revenues in the 2010 federal budget. The budget allocates 41 percent of revenues to education, health care, and social affairs, such as financial assistance for low-income families. The new budget represents a 21 percent increase over the 2009 allocation for the same sectors.

Education

the overall literacy rate for the population aged 15 to 24 at more than 90 percent. The UAE’s government has significantly increased funding for education since the 1990s, spending USD 1.5 billion in 2003, compared with USD 67.3 million in 1994. Public education is provided by the federal government free of charge for all citizens, from kindergarten through university.

The UAE has one of the lowest pupil-to-teacher ratios (12:1) in the world. Education is compulsory through the ninth grade, although this requirement is not enforced. Children of citizens attend gender-segregated schools. In 2004 and 2005, some 9.9 percent of students in grades one to five and 8.3 percent of students in grades six to nine did not complete their education. The rate was 9.3 percent in grades 10-12. Overall, 38.1 percent of citizens are younger than 14 years, and 51.1 percent are under 20. There are enormous and increasing demographic pressures on the education system.

Students choose to attend private schools, most of which serve the educational needs of expatriate children. These vary in curricula, the background of the students, tuition, and quality of education. In K-12 schools and colleges, and universities, private education is one of the fastest-growing business sectors in the UAE. Many expatriate workers’ employers offer educational subsidies to cover part or all of the educational costs of their employees’ children. The oldest and perhaps most prestigious of these schools is the American School in Dubai. The largest private educational company is the Indian-owned Varkey Group.

Higher education

In higher education, three main federal institutions are catering to more than 30,000 Emirati students:

• UAE University, in al-Ain; 16,000 students; instruction in Arabic and English.

• Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT), which has 16 segregated campuses countrywide; more than 16,000 students; instruction in English.

• Zayed University (2 campuses), in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, with segregated male-female sections; about 6000 students; instruction in English.

Private universities offer a wide range of educational opportunities in the UAE. These include, for example, the American universities of Sharjah and the American University in Dubai, Sharjah University, and the Ajman University of Science and Technology. Other less well-known institutions include al-Hosn University and al-Ghurair University. Many international universities have moved to the UAE, especially Dubai, to offer degrees in certain specialties, where they tend to operate from free-zone educational complexes, such as the Dubai Knowledge Village and the Dubai International Academic City. In Abu Dhabi, the Paris Sorbonne and New York University have established large campuses offering opportunities similar to those students have access to on their home campuses.

The Ministry of Education has adopted ‘Education 2020′, a series of five-year plans designed to introduce advanced education techniques, improve innovation, and focus more on students’ self-learning abilities. As part of this program, the government began offering, in all government schools, an enhanced curriculum for mathematics, science, and English from the first-grade level, starting in the 2003-2004 academic year. Further support was given to the improvement of education in 2006, providing modernized classrooms, computer laboratories, and other facilities.

Health

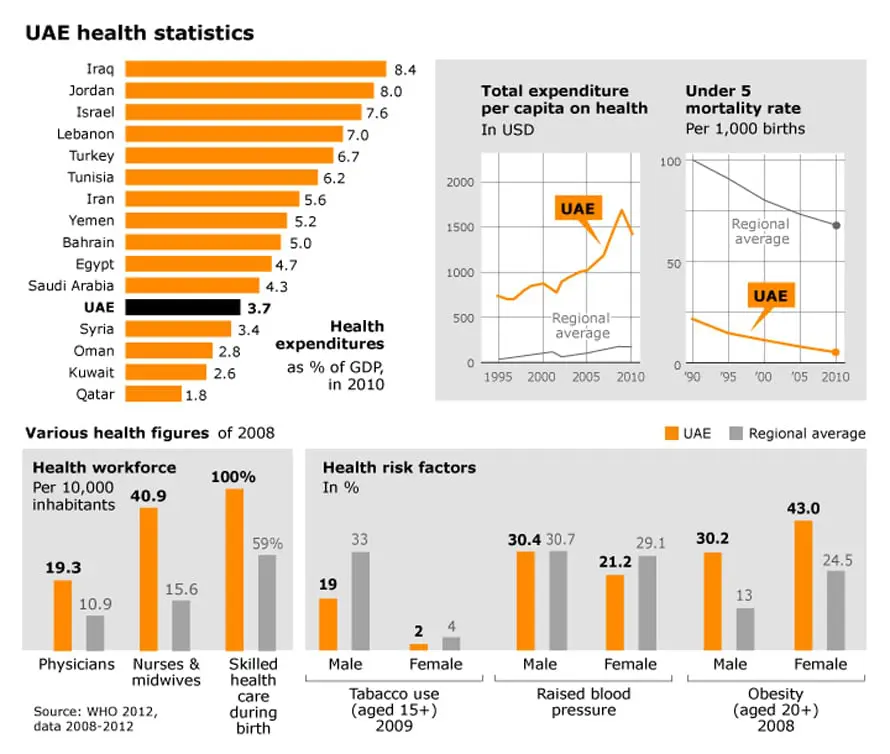

Standards of health care in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are considered generally high, as result of significant government spending on this sector. In 2002, total expenditures on health care were 3.1 percent of GDP; in that same year, the per capita expenditure for health care was USD 802. Health care is free only for UAE citizens. Since January 2006, all Abu Dhabi residents have been covered by a comprehensive health insurance program, in which costs will be shared between employers and employees. The number of doctors per 100,000 (annual average, 1990-2003) is 177. The UAE now has 40 public hospitals, up from seven in 1970. The Ministry of Health is undertaking a multimillion-dollar program to expand and modernize hospitals and other health facilities. Dubai has also developed Dubai Healthcare City, a free-zone hospital that provides international-standard health care and an academic medical training center.

Cardiovascular disease is the principal cause of death in the UAE, constituting 28 percent of total deaths; other major causes are accidents and injuries, malignancies, and congenital anomalies. In 1985 the UAE established a national program to prevent transmission of AIDS and to control its entry into the country. According to World Health Organization estimates, in 2002-2003, fewer than 1,000 people in the UAE were living with HIV/AIDS.

Women

Women’s equality is not clearly established in the UAE Constitution. In practice, women’s social, economic, and legal rights are not equally protected or consistently observed because of traditional and institutional biases against women and the incomplete and selective implementation of laws. Women’s lives in the UAE and the laws that govern them differ dramatically, depending on their citizenship and employment status conditions.

Legal protection of women’s rights in the UAE, such as the right to equality before the law, tends to be applicable and enforceable mostly in the public sphere, outside the home, which is off-limits to most UAE women. Women’s rights at home are thus inadequately protected legally. Fathers and husbands exercise power over women, including the legal authority, to prevent their daughters and wives from participating in professional and social life.

In some UAE legislation, women are discriminated against because of their gender, as, for example, in-laws governing citizenship. Foreign women who marry male UAE citizens are routinely granted citizenship, but female UAE citizens cannot transfer their nationality to their foreign-born husbands. A female UAE national is forbidden by law to marry a foreign man, and a 1996 law requires her to renounce her UAE citizenship if she marries a person from outside the Gulf region.

Migrant Women

Foreign women constitute the largest domestic workers in the UAE, working as drivers, cooks, nannies, and housekeepers. Most of these women come from South and South-East Asia and work with little legal protection under harsh conditions. UAE labor laws do not apply fully to domestic workers, and these women have few rights. Employers, who sponsor their visas, have the legal power to control their domestic workers, often resulting in severe abuse, limiting their freedom of movement, exploitation, and interfering with their dress and religious activities. Many domestic workers are subject to racism and ill-treatment from household members and may labor under slave-like conditions. The average domestic employee works fifteen hours a day, seven days a week.

About 50 percent of the female domestic workers interviewed for the International Labour Organization’s Gender Promotion Programme reported being abused verbally, physically, and/or sexually. The abusers may be their employers, family members of the employers, or even visitors. Many domestic workers are afraid to report abuse and live with it for fear of being accused of illicit sex, a crime that can be punishable by death in the UAE. Marnie Pearce, a British national, was sentenced to 90 days’ imprisonment for adultery (she was released after serving 68 days in April 2009). Housemaids who run away from their employers and are caught by the police – or even those who approach the police to report abuse – risk arrest and imprisonment by the immigration authorities.

Labour Force

The UAE has a small national population, and its labour market is mostly dependent on expatriate contractual labourers, who comprise about 81 percent of the country’s total population. The total labor force in the UAE is 3.908 million. By 2009 estimates, expatriates account for about 85 percent of the workforce. Given the demographic and economic realities, it seems that the UAE will continue to be reliant on foreign migrant workers to meet its rising need for skilled and unskilled labor for a long time to come. Local Emiratis are generally employed in the government and public sectors and in certain private companies that must meet a government quota of hiring a specified percentage of locals as part of a program to nationalize the workforce, also known as Emiratization gradually. Nationals make up only 10-15 percent of the labor market.

Population size, age composition, and social factors have a strong impact on the UAE labor force’s nature and size. Most of the labor force in the UAE consists of males, 88 percent of whom are under 45 years of age. One reason for the gender imbalance in the labor force is that the lowest-paid workers cannot bring their families with them. Female participation in the labor market remains relatively small, 16.3 percent in 1999. According to the IPR Strategic Business Information Database (19 October 2005), a recently publicized study by the National Bank of Dubai shows that national women represented 15.2 percent of the overall labor force in the UAE in 2004′. Among these, Dubai absorbed 36 percent of the total number of working women in the country. The share of females in the country’s labor force in 2008 was 15.5 percent.

The unemployment rate is relatively low, usually no more than 4 percent. According to another study, by The National Human Resources and Development Authority (Tanmia), ‘In 2003 an estimated 73 percent of the population was in the 15-59 age-group and the labor force participation[LFP]…rate for the same year, was approximately 61.5 percent, ranging from a low of 47.7 percent for Ras al-Khaima to a high of 68.6 percent for Dubai. Disaggregation by gender shows that the male LFP rate is more than twice that for women, with 2003 estimates of 77.2 percent and 28.2 percent, respectively.’

The workforce broadly reflects the ethnic distribution of the population, consisting of approximately 19 percent Emirati nationals, 19 percent other Arabs and Iranians, 50 percent South Asians, and 8 percent expatriates from Western and other countries. Most white-collar jobs in private companies are held by Western, Arab, and Indian expatriates. The bulk of employees in the service sector are South Asians or from the Philippines, and cleaning and construction jobs are reserved for South Asians, especially Indians, Pakistan, and Bangladeshis. The latter is the largest single group of workers in the UAE; real estate and public projects are the most extensive part of the economy. The need for workers is therefore almost insatiable.

Minimum wage

The UAE has no minimum wage established, except for some professions, such as teachers and maids/nannies; there is thus a wide range of pay for similar jobs (even within the same organization). Inflation rates and living costs differ among emirates and cities (Abu Dhabi International Airport now has the highest remuneration packages). Despite the lack of sufficient compensation for the erosion of salaries and wages, the UAE’s salaries are still better than in many other places. Salary growth in the UAE in 2008 was 13.6 percent (while in the Gulf Cooperation Council as a whole, it was 11.4 percent). The UAE’s incremental increase in base pay in 2009 was 2.4-5.2 percent, better than that in other countries, such as the United States (1.9-2.2 percent), Australia (2.0-3.0 percent), and Germany (2.1-2.5 percent).

Human Trafficking

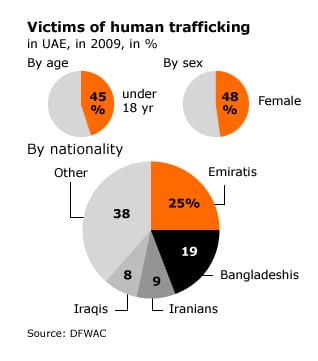

The UAE is an international centre of human trafficking, especially in women and children. According to reports in 2010, human trafficking accounted for a shocking 37 percent of all cases referred to the Dubai Foundation for Women and Children (DFWAC) in 2009, an increase of 28 percent from 2008.

Information from DFWAC’s annual reports shows that 89 cases were referred to the center in 2009, including child abuse and domestic violence cases. Of these, 45 percent involved children under the age of 18, and 48 percent of the victims were females. Emiratis (24.7 percent) constituted the largest group of cases (24.7 percent), followed by Bangladeshis (19 percent), Iranians (9 percent), and Iraqis (8 percent). Other nationalities, with one to four victims each, made up the remaining cases.

A documentary program on al-Jazeera in 2009 told the story of an Uzbek woman, ‘Svetlana,’ who was forced to work in the sex trade in Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The woman recounted how she was lured into prostitution after being offered a job as a waitress. Still, her passport was taken away from her, and she was threatened with harm to her family if she refused to co-operate. After years of abuse as a sex slave, a common practice, ‘Svetlana’ finally managed to find refuge at the United Arab Emirates’ shelter for the victims of human trafficking, the Abu Dhabi Shelter for Women and Children.

Camel jockeys

Until a few years ago, very young children were trafficked from South Asia to work as camel jockeys during the popular camel races in the UAE. Boys from Bangladesh and Pakistan, given their availability and small size, have traditionally been the choice. The Bangladeshi National Women Lawyers’ Association estimated that as many as 7,000 boys were smuggled out of Bangladesh during the 1990s for camel races. The trade continued despite the official ban on the use of camel jockeys younger than fifteen in 1980. Some reports alleged that the purchased children were abused or beaten to force them to comply with the racer’s demands. The trade-in camel-jockey boys were finally eradicated in 2005, and all children were repatriated to their families in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Robot camel jockeys have replaced Camel-jockey boys.

Combatting human trafficking

The trafficking of women and girls used in domestic service in the country continues unabated. The victims reportedly come mostly from Sri Lanka, Indonesia, India, and the Philippines. For the UAE’s sex industry, women from Central Asian and Eastern European countries are more often targeted. The government has taken steps to combat human trafficking, but it remains to be seen how effective they will be. For example, the Ministry of Interior has set up the Anti-Human Trafficking Panel to coordinate competent authorities, care for victims, and update the legislature. The UAE has supported the UN Global Plan of Action to Combat Human Trafficking. Anwar Mohammed Gargash, UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs and chairman of the UAE National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking (NCCHT), expressed the UAE’s agreement with the main features of the international initiative to combat human trafficking, launched on 31 August 2010, which calls for setting up of an UN trust fund for victims of trafficking, especially women and children.

Position of NGOs

The government generally does not allow organizations to focus on political issues but has tolerated a few groups that engage in some kinds of human-rights monitoring and advocacy. There are two recognized local human-rights organizations, the quasi-independent Emirates Human Rights Associations (EHRA), which focuses on labor rights, stateless persons‘ rights, and the treatment of prisoners; and the government-subsidized Jurists’ Association Human Rights Committee, which concentrates on human rights education and conducts related seminars and symposia, subject to government approval. However, the board of directors of the Jurists’ Association was dissolved in April 2011.

Although a government prosecutor heads EHRA, it generally operates without government interference, except for requirements applicable to all associations in the country. The UAE government directs and subsidizes NGO members’ participation in events outside the country, such as international human-rights conferences. All participants in such events, whether or not they are speakers, must obtain government permission to attend.

The government does not allow international human rights NGOs to be based in the country but does allow limited visits by their representatives. No transparent standards govern these visits, but the government generally showed some cooperation with certain international organizations, including the UN Children’s Fund and the UNHCR. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has an office in the UAE.