Justin Salhani

Water scarcity in Iraq could lead to further instability and displacement in coming years as climate change and regional projects by Turkey and other neighbors threaten the country’s water supply. Without modernizing the water architecture, regional agreements and diversifying the national economy away from oil, Iraq’s long term stability is in jeopardy, according to analysts.

“Tension elevates every time there is a drought,” Harry Istepanian, an expert in Iraq’s energy and water sector, told Fanack.

Temperatures have sharply risen in Iraq in recent years. The last century has seen an increase of 0.7 degrees Celsius, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross. As the average temperature goes up, the land inevitably becomes less fertile and hits local residents and industry.

Warming rates in the Middle East are rising faster than the global average. Heatwaves are becoming more frequent and more severe, leading to increased salination of the farmable land. As temperatures continue to rise, Iraq’s most vulnerable will face increases in malnutrition and hunger.

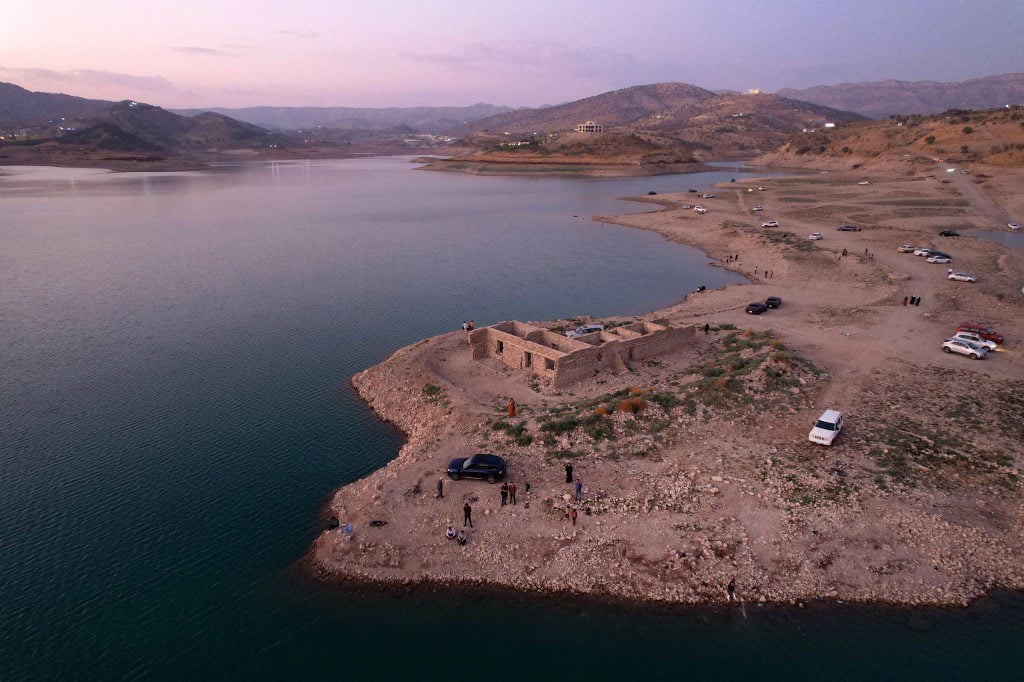

In the summer of 2018 in Basra, 118,000 people were hospitalized with health issues related to water quality. In 2019, the United Nations International Organization for Migration reported the internal displacement of 21,314 Iraqis in central and southern governorates due to a lack of drinkable water. Iraqis in large swathes of the country will continue to flee their homes in the coming years as 54 percent of Iraqi land is under threat due to increased salination. In the south of Iraq, oil fields have polluted sources making the water non potable while the second largest lake in the country has completely dried up.

“We go out to sea for eight to 10 days and when we return, we’ve caught between 500 kilograms and one tonne, compared to three or four tonnes 20 years ago,” an Iraqi fisherman named Abdallah told France 24.

Farmers who make up the country’s agriculture sector, which consists of only around 5 percent of Iraq’s GDP but employs around one-third of the country’s citizens who live in rural areas, are expected to take the biggest hit. Droughts have also hit other sectors including the southern marshes where water buffaloes and other animals are bred, forcing people to grapple with the prospect of fleeing for a more stable environment.

“Most of the farmers, I would say 70 percent of the families, abandoned their lands,” Istepanian said. “It’s changing the entire landscape of the population and even the ecosystem.”

Meanwhile, concerns over a lack of water are not only domestic but also regional. Iraq’s main water sources are the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. They provide 98 percent of the country’s surface water. Both rivers originate in Turkey, with the Euphrates running through Syria, and tributaries cutting through Iran. Turkey in particular has built 22 dams and 19 hydraulic plants as part of its Southeastern Anatolia Project which allows it to control the water supply running into Iraq and Syria. Both rivers could be completely dry in Iraq by 2040 due to the actions of Iraq’s neighbors.

“For the last 75 years, Turkey and Iran both refused to sign any mutual agreement with Iraq simply because they don’t consider the rivers as transboundary rivers,” Istepanian said. “In the absence of any agreements between the countries, Turkey is saying they will satisfy domestic requirements and capture as much as possible from the two rivers before they allow water to flow to Syria, in case of Euphrates, or to arrive [in Iraq] in case of Tigris.”

Regional talks are ongoing over the water issue but Istepanian said there is no guarantee Turkey, the major cardholder in this interaction, will change tact. As changes on the climate impact Iraq’s neighbors in the coming years, it will also mean even less water entering Iraq.

“It’s a compounding problem for Iraq,” Istepanian said. “Not only that there’s no water but they have to do more with regards to water management.”

Attempts to modernize the water management infrastructure are underway but widely recognized as moving too slow. More than three quarters of Iraq’s water is currently used for irrigation. The World Bank’s Economic Monitor has called for “dramatic sector reforms to capture opportunities and manage risks.” It has also called on Iraq to be more efficient and productive in managing institutional and regional solutions.

“The way in which fields are irrigated has been used for the last 4000 years in Iraq,” Istepanian said. “Iraq needs to develop new technologies in the absence of any agreement with Iran and Turkey and needs to look to capture water from other sources like rain.”

The Shatt Al Arab river in Iraq finds 40 percent of its water from Iran and the two countries have disputes over the water source dating back more than 85 years.

While various Iraqi governments have tried with international backing to find solutions for their water needs, there’s been little success to date. Istepanian said the Iraqi state realizes it also needs to diversify its economy away from oil dependency but that such moves are way too slow. Much of the government’s focus in recent years has been in countering groups like the Islamic State, fighting corruption, or confronting regional military issues.

International groups and organizations like the World Food Programme, the European Union and UNICEF, among others, have looked to modernize Iraq’s water infrastructure by rehabilitating canals, pumps and irrigation networks in parts of the country as well as various industry-specific training. But without a wider regional understanding, Iraq’s economic, social and geographic makeup will continue to suffer.

Istepanian said that while widespread changes are needed in the long term, the short term will likely be tumultuous and vary from year to year. Strong rainfall and snow in parts of the country could sustain segments of the population this year, though should another drought arise – and it is a question of when, not if – the same problems will rear their heads once more.

“I was expecting things to be worse this year. Thank God that they had a good rain season,” Istepanian said. “But the crisis is still there.”