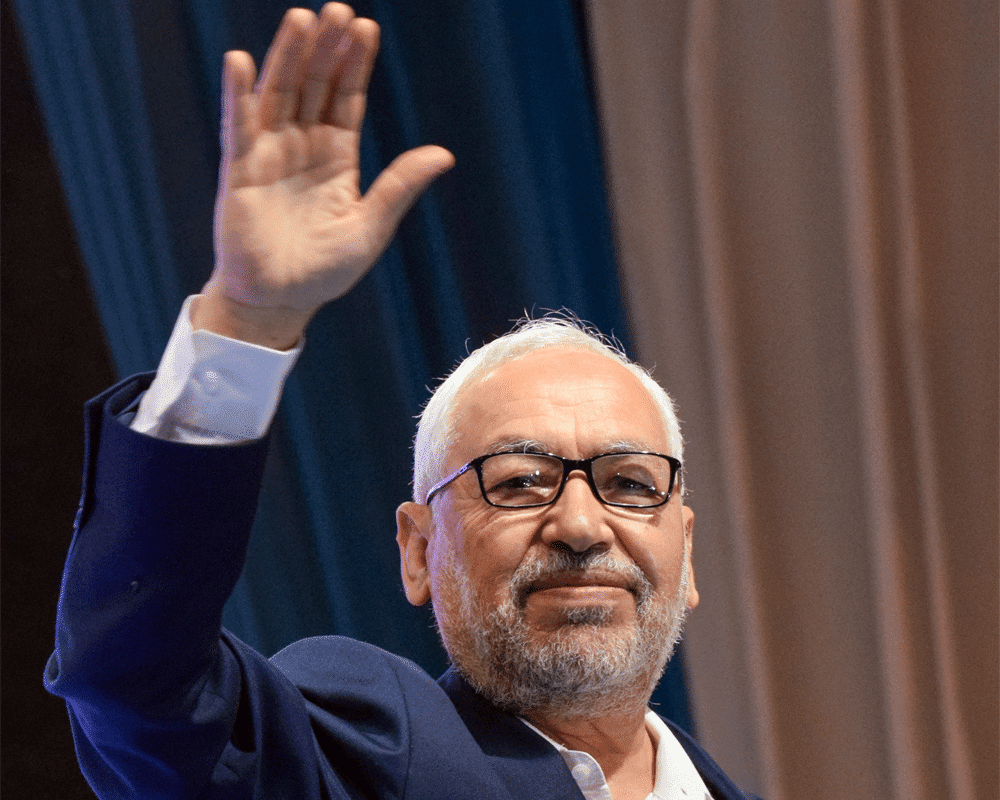

Rachid Ghannouchi, founder of the Tunisian Islamist movement Ennahda, evolved from a Nasserist Social Unionist to an Islamist in 1966. He is currently one of the most prominent modernizing Islamist thinkers in the Arab world.

Rachid Ghannouchi is the founder of the Tunisian Islamist movement Ennahda and one of the most prominent modernizing Islamist thinkers in Tunisia and the Arab world.

He was born in Tunisia in 1941 into a modest Muslim family who influenced his early understanding of traditional Islam. He completed his high-school education in Jamee Zaitouna, then moved to Egypt and later Damascus, where he studied philosophy. In Syria, he was exposed to various political ideologies, including Nasserism and Baathism, but he followed the Islamist current in the university and, after the Arab-Israeli war of 1967, called on fellow students for armed struggle to free Palestine. Ghannouchi wrote extensively to advance the Palestinian cause and armed resistance against Israel.

He evolved from a Nasserist Social Unionist to an Islamist in 1966. While still in Syria, he often attended meetings of the Muslim Brotherhood, Jamaat Albanin, and other Salafist, moderate, and Sufi Islamist groups.

Soon after graduating from Damascus, he flew to Paris, initially with the aim of completing postgraduate work at the Sorbonne University. Paris was also a major influence on his life as a thinker and a leader. He began to attend gatherings of North African students, who were often Marxists. He then joined the apolitical grassroots Islamic movement Jamaa Tabligh and Daawa, in which he became an imam and played a part in preaching the basic teachings of Islam by approaching people, usually Muslims.

He spent a year in Paris before returning to Tunisia, where he resumed his affiliation with Tabligh for three more years. However, the public approach of Jamaa Tabligh was judged inadequate in the context of the Tunisian government. This led him, along with the rest of his group, to adoapt the Muslim Brotherhood approach, that organization being more of an underground movement.

When in Tunisia, he met Abdel Fattah Moro, deputy president of the Tunisian parliament. With a few other Tunisian friends, they founded the country’s Islamist Group in 1972. When Tunisia’s then president Habib Bourguiba opened the country to democracy, Ghannouchi and his colleagues decided to dissolve the Islamist Group and in 1981 founded a new movement, the Islamist Direction Movement, which is now Ennahda. However, the movement was never granted a licence, so its activities were illegal. The movement held to democracy and declared itself a champion of the poor and vulnerable. The party’s presidency was entrusted to Ghannouchi, and Morro was appointed secretary general.

Ennahda

Sheikh Ghannouchi distinguishes his movement in Tunisia from other Islamist movements in the Arab world because it links its Islamist ideology with the traditional Tunisian Maliki school of religious law, Oriental Reformist ideology, and modern rationalist culture. Ghannouchi is known for his militancy in attempting to modernize Tunisia. He believed that the Tunisian government is, by nature, always seeking modernization. Unlike the government of Bourguiba, who saw modernization as the “Westernization” of Tunisia, Ghannouchi’s Islamist movement restricted itself to the modernization of society within Islamic boundaries.

However, the Tunisian secular government restricted his activities beginning in the late 1970s. He was first jailed for his political activities in 1981. In 1987, Bourguiba called for sentencing him to death, but Ghannouchi was lucky to have his life saved by none other than Ben Ali: because of Ben Ali’s coup that overthrew Bourguiba in late 1987, Ghannouchi was released from prison. Ghannouchi eventually had to flee Tunisia. His condemnation of violence and advocacy of human rights were a threat to Ben Ali’s regime, which sentenced him to life in prison. Ghannouchi travelled to Algeria and Sudan before being granted political asylum in the UK in 1993. From exile, he continued to serve as elected president of what had become known as the Ennahda movement.

After the Tunisian Revolution of 2011, he returned to his home country and mobilized Islamists to reintegrate themselves into the Tunisian democratic process. Despite the remarkable victory of Ennahda in Tunisia’s first democratic elections of October 2011, Ghannouchi refused to take any political position and promised not to run for the presidency.

Ghannouchi played a major role in helping Tunisia become what it is today, the first free country in the Arab world, according to a recent report by Freedom House. He stood up against tyranny during Tunisia’s two dictatorships and urged inclusive political dialogue and compromise to achieve a functioning unity government in the post-revolution period. Before the 2014 legislative elections, Ghannouchi argued boldly for the neccessity of an inclusive coalition government including whatever politicians the Tunisians vote for, including secularists and figures who served in the former Ben Ali regime.

Ghannouchi was awarded the 2014 Ibn Rushd prize for freethinking and the 2012 Chatham House Prize, which he won jointly with Moncef Marzouki, the then interim president of Tunisia.