Introduction

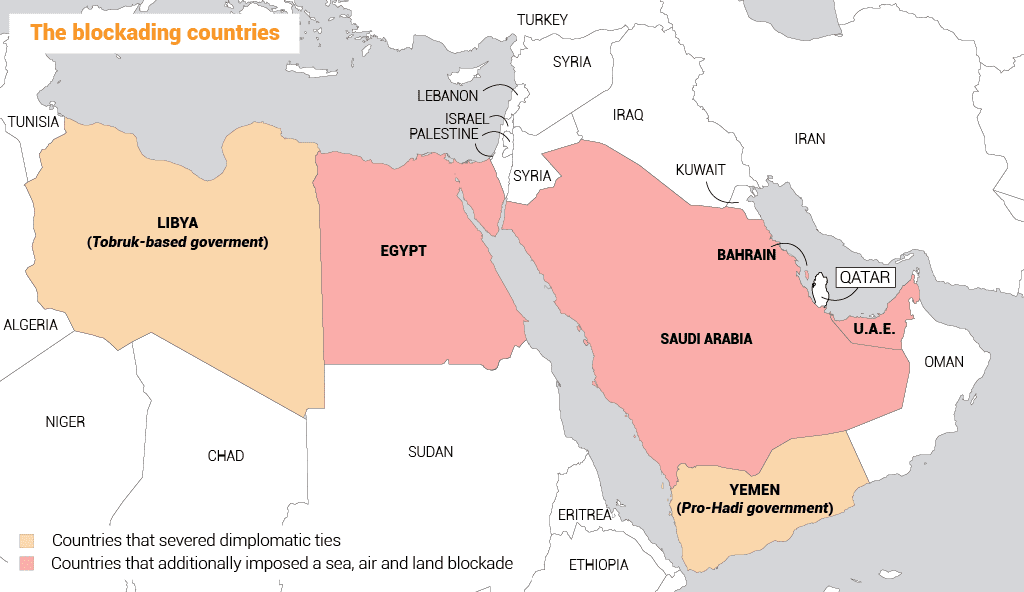

On 5 June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates(UAE), Egypt, Bahrain, the Yemeni government-in-exile, and the Libyan government based in the eastern part of the country cut diplomatic ties with Qatar. The tiny gas- and oil-rich country, which for years has been punching above its political weight, saw itself facing its most severe diplomatic crisis since it declared its independence from Britain on 3 September 1971.

Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE, and Bahrain added that they would halt land, air, and sea traffic with Qatar, eject their diplomats and order their nationals living in Qatar to leave.

This was with the exception of Egypt, which has around 250,000 expats living and working there. Moreover, Qatar was expelled from the Saudi-led coalition fighting the Houthi rebels in Yemen. The crisis expanded days later when Mauritania, the Maldives, and Mauritius also announced they were cutting diplomatic ties with Qatar.

The coordinated move, which escalated a longstanding dispute over Qatar’s alleged support of Islamist groups, created uncertainty in the country, which shares its only land border with Saudi Arabia and imports an estimated 40 percent of its food from the kingdom.

Photographs of Qatari supermarkets with empty shelves and long queues of people stockpiling food flooded social media and news websites. Qatar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the measures were unjustified and based on fake news, a reference to claims that the website of its state-run news agency had been hacked in late May 2017. Qatar accused other Gulf states of violating its sovereignty as the Qatari stock market tumbled and oil prices rose.

Qatar agreed for the US to send the FBI to Doha to help the Qatari government in its investigation into the alleged hacking incident that contributed to the crisis. On 7 June 2017, CNN reported that the intelligence gathered by the US security agency indicate that Russian hackers were behind the breach.

On 30 May 2017, the Saudi-owned al-Arabiya news website published a series of demands that diplomatic sources said would be ‘binding’ in any agreement reached between Qatar and other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council(GCC). These demands include:

1. Stop interfering in the internal affairs of Gulf states and Arab countries.

2. Stop incitement through Qatari media channels.

3. Halt the naturalization of any more citizens from other Gulf states.

4. Stop incitement against Egypt through its policies.

5. Stop supporting the Muslim Brotherhood Islamist group.

6. Deport persons who are hostile to other GCC countries from Qatar’s territories, especially members of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain last cut ties with Qatar in 2014, prior to the Riyadh Agreement, withdrawing their ambassadors from the country for nine months. The blockade imposed in 2017 was the worst to hit the Gulf since the formation of the GCC in 1981.

In addition, the main problem that triggered the rift was never healed. Even though the Qataris toned down al-Jazeera’s coverage, closed the al-Jazeera office in Cairo, and evicted a few Muslim Brotherhood members from the Qatari capital Doha, its ambition to be a regional actor never wavered, neither did its links with a host of political Islamists across the region, enraging the UAE, which has zero tolerance for the Muslim Brotherhood.

Many analysts linked the most recent escalation to the visit by US President Donald Trump to the Saudi capital during the Riyadh Summit on 20-21 May, when he ardently embraced a Saudi narrative of being a partner in the fight against terrorism and countering Iran’s influence in the Middle East.

In a series of tweets, Trump appeared to take credit for the decision by Saudi Arabia and its allies to cut diplomatic relations with Qatar, an important American ally, approving the move even though the Pentagon and State Department attempted to remain neutral.

“During my recent trip to the Middle East, I stated that there could no longer be funding of Radical Ideology. Leaders pointed to Qatar – look,” he tweeted. He later changed course, ringing the Emir of Qatar and offering US help in finding a solution to the crisis.

Qatar hosts the US Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at al-Udeid Air Base, which provides command and control of airpower throughout Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and 17 other nations. It has played a vital role in the US so-called war on terror.

On 6 June, Qatari Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani spoke to CNN’s Becky Anderson, saying that Saudi accusations that his country supports terrorism were “full of false information.”

“With all due respect, this statement is full of contradictions because it is saying that we are supporting Iran and on the other hand supporting the extremist groups in Syria, and we are supporting the Muslim Brotherhood in Saudi or Yemen, and we are supporting the Houthis from the other side. In all battlefields, there are adversaries,” al-Thani said.

Qatari capital Doha, its ambition to be a regional actor never wavered, neither did its links with a host of political Islamists across the region, enraging the UAE, which has zero tolerance for the Muslim Brotherhood.

According to an article in the Financial Times, Qatar paid a ransom of $1 billion to an al-Qaeda affiliate and Iranian security officials to release members of its royal family who were kidnapped in Iraq while on a hunting trip.

This was “the straw that broke the camel’s back”, according to one Gulf observer, who asked not to be named. The Saudis and Emiratis seemed determined to use this as evidence of Qatar’s policy of fuelling both sides of the conflict.

Qatar’s foreign Policy

Doha has a history of reaching out to controversial groups and figures. From Taliban leaders and rebels in Sudan to Hamas leaders and even Hezbollah, it usually positions itself as a neutral player that acts as an intermediary in regional conflicts through its diplomatic backchannels.

However, according to Doha’s harshest critics – mainly Saudi Arabia and the UAE – Qatar uses such policies to play both sides in order to fund radical Islamist groups. The hostage deal was further evidence of that role, they say. Similar accusations are frequently aimed at Saudi Arabia itself.

The Emirati’s main concern is the Muslim Brotherhood, which it regards as a terrorist organization that poses a threat to its system of hereditary rule. However, for Saudi Arabia, the Atlantic’s article titled ‘Qatar: The Gulf’s Problem Child’ best explains the relationship between a regional power and a small state wanting to play a big role.

Abdel Bari Atwan, veteran Arab journalist and editor-in-chief of the Kuwaiti Rai al-Youm newspaper, said in a televised interview with Euronews that Qatar has paid the price for attempting to pursue an independent foreign policy to Saudi Arabia. He said that if it does not concede to Saudi and Emirati demands, it faces the real prospect of military invasion and regime change.

Surviving the Blockade and its Effects

In November 2017, the bloc expanded an existing blacklist of groups and individuals with alleged terrorist ties to include two more organizations, the International Union of Muslim Scholars and the International Islamic Council for Dawah and Relief, and 11 individuals, including the director of relief and international development at the Qatar Red Crescent. All have allegedly ‘carried out various terrorist operations in which they have received direct Qatari support.’

However, wealthy Qatar proved able to cope with the economic blockade imposed in June 2017 by dipping into its financial reserves and expanding its dealings with Iran and Turkey.

The trade restrictions initially raised concerns of an impending food shortage in Qatar, which imports about 40 percent of its food through Saudi Arabia and much of the rest through UAE ports. The situation has turned out to be less dire. The International Monetary Fund noted in October 2017, ‘After the initial shock of the [5 June 2017] measures, the Qatari economy and financial markets are adjusting to the impact of the diplomatic rift.’ Likewise, the World Bank observed that the oil and gas sector, which accounts for 80 percent of exports and 90 percent of government revenues, has seen little effect from the blockade.

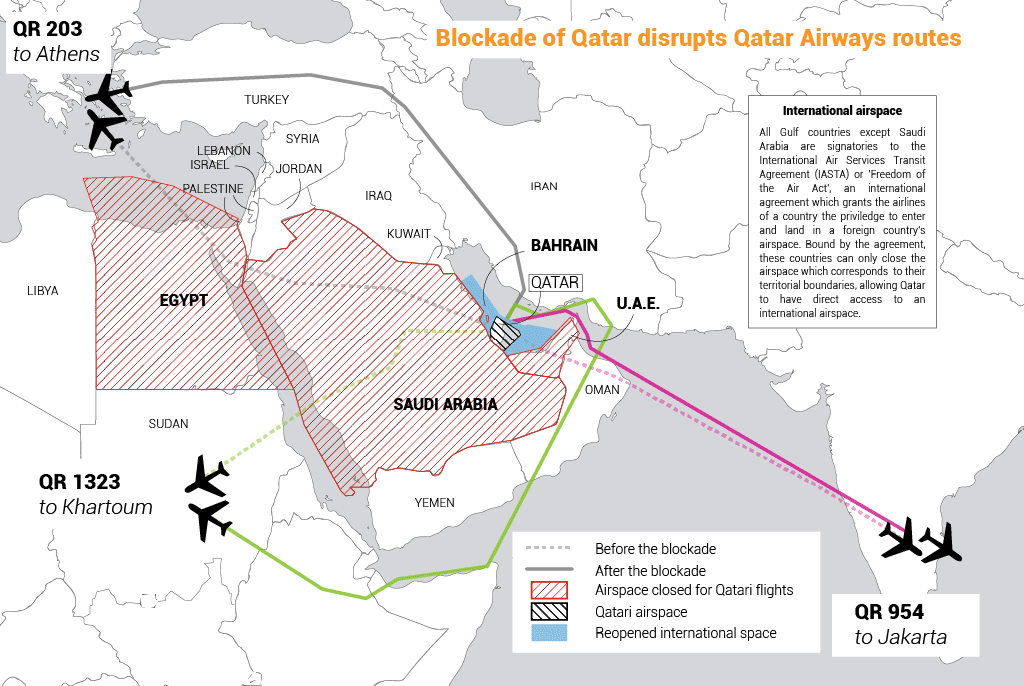

Other sectors have been harder hit, most notably the state-owned airline Qatar Airways. The airline’s CEO Akbar al-Bakr expected to report an annual loss due to the blockade, which had forced the company to cancel some routes and redirect others to take longer routes, leading to higher fuel costs.

In the short term, Qatar found shipping routes via Oman and Kuwait, completed the new $7.4 billion Hamad seaport to support alternate trading routes, and increased its imports from Turkey and Iran to make up for the lost trade from its Gulf neighbours. In August 2017, non-food imports from Iran were up by 60 percent from the year before.

Qatar’s increasing dependence on Iran is a predictable but nevertheless ironic result of the blockade, as one of Saudi Arabia’s major grievances is Qatar’s relationship with Tehran.

Qatar is better positioned than most countries to withstand the economic impacts of the blockade: it is the largest exporter of natural gas and one of the richest country’s per capita in the world. As of July 2017, Qatar had about $340 billion in reserves at its disposal – $40 billion in the Central Bank and $300 billion in the Qatar Investment Authority sovereign wealth fund, according to the Central Bank Governor Abdullah bin Saud al-Thani. However, Moody’s credit rating agency reported that Qatar spent $38.5 billion in reserves to support its economy in the first two months of the blockade. In addition, the ongoing crisis has made investors uneasy, in part because the disruption to trade hurts not only Qatar but also the countries enforcing the blockade.

“The severity of the diplomatic dispute between Gulf countries is unprecedented, which magnifies the uncertainty over the ultimate economic, fiscal and social impact on the [Gulf Cooperation Council] as a whole,” said Steffen Dyck, vice president of Moody’s, following the release of a report that found that the dispute could hurt the credit rating of all members of the GCC.

Investors from the blockading countries pulled money out of Qatar, sending the stock index plunging by 22 percent.

Despite this, Qatari officials adopted an optimistic tone. In a speech on 21 November 2017, Rashid Ali al-Mansoori, the head of the Qatar Stock Exchange, said, “We passed the blockade shock and are operating as normal.” More than 100 new foreign funds have invested in Qatar since the blockade was imposed, Mansoori added, although he did not say which ones.

Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani also brushed aside the effects, saying: “The negative impacts of the blockade were temporary, and our economy has managed to contain most of them very quickly while adapting and developing itself in the course of the crisis management.”

General Gross Government Debt of Qatar

2010-2020 (as % of GDP)

Qatar’s Imports from Iran and Turkey

2012-2019 (in US$ Million)

Qatar’s Imports from Saudi Arabia

2012-2019 (in US$ Million)

Rapprochement

Despite divisions between members of the GCC due to the blockade, the block of Gulf states presented a united front during its yearly summit on 10 December 2019 in the Saudi capital Riyadh. This unity included Qatar, despite the ongoing land, sea, and air blockade.

In December 2019, Qatar’s foreign minister told a conference in Rome that the Gulf crisis has “moved from stalemate to progress.” He revealed that talks had taken place between Qatari and Saudi officials without providing further details. The three GCC blockading countries also took part in a regional football tournament in Qatar, reversing an earlier decision not to participate at the last minute.

Analysts recognized that circumstances in the region had changed, prompting a change in the attitude of the parties involved, but said more was needed to reach a long-term resolution.

“While there have been rumours of rapprochement in the past, this time it appears to be different,” April Longley Alley, MENA deputy program director for the international non-profit organization the International Crisis Group, told Fanack. “There are strong financial incentives for both sides to end the standoff, and possibly the collective security risk posed by Iran post the Aramco attack could incentivize cooperation.”

The Aramco attack occurred in September 2019, when missiles and drones hit two state-owned facilities in Saudi Arabia, knocking out almost half of the country’s export capacity and around 5 percent of global oil production. Yemen’s Iran-aligned Houthi group, which is battling a Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, claimed responsibility for the attacks, although few believed them. One possibility is that pro-Iranian Iraqi militias were behind the strikes.

“Maybe most important is a shift in Saudi Arabia,” Longley Alley added. “Since the Aramco attacks and as the kingdom focuses more on its domestic reform agenda, Riyadh appears to be shedding or reducing its involvement in diplomatically and/or financially costly regional conflicts [like Yemen and Qatar] and taking at least some steps to lower the temperature with Iran.”

She continued, “While both Qatari and Saudi officials are generally positive about the direction of efforts to restore relations, differences remain deep. Even if an agreement is reached, diplomatic relations are restored, and the blockade lifted, tensions will likely remain. And while the UAE would need to go along with the Saudis, they may do so only reluctantly, and their relations with Qatar will remain especially fraught and unlikely to mend quickly.”

Talha Abdulrazaq, a researcher at the University of Exeter’s Strategy and Security Institute, expected a careful rapprochement between Qatar and the quartet. “Ideally, it would be to return to a pre-blockade condition, a status quo ante where the GCC was largely in lockstep, at least publicly, even if they privately feuded. This would mean a restoration of access to each other’s countries and air spaces and the resumption of meetings involving all the Gulf powers. Egypt is not part of the GCC, but it is very much a junior partner in the quartet and would not continue unilaterally should Saudi Arabia mend fences with Qatar.”

Despite indications that Saudi Arabia and Qatar were willing to put the tensions aside in order to present a more united front during troubled times, major changes were hard to come by. For instance, King Salman of Saudi Arabia invited Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani to the GCC summit in Riyadh. He refused the offer and sent a junior delegation instead, taunting the Saudis.

“There have been positive noises coming from both Qatar and Saudi Arabia, but the UAE is clearly unhappy with any increased understanding fostered between Riyadh and Doha,” Abdulrazaq said. “The GCC summit was held in the aftermath of the attack on vital Saudi oil infrastructure, causing shocks to the global oil market and temporarily slowing down supplies. Saudi Arabia was looking for a general condemnation of Iran and its malign activities throughout the region, and it managed to issue a joint communique that was a watered-down version of that. It wasn’t, therefore, a decisive summit and changed very little on the ground.”

Saudi Arabia

More than three years into the Gulf crisis, which has exacerbated divisions in the region, Qatar and Saudi Arabia seemed to come closer to an agreement. An announcement by Kuwait, which mediated in the dispute, in early December 2020 stated that Riyadh and Doha have “confirmed an agreement” to reach a solution that restores “Gulf solidarity.”

Nonetheless, the Saudi Foreign Minister said that an agreement with Qatar was within reach, but analysts remained skeptical that the Gulf dispute would come to a definitive end.

According to Andreas Krieg, a lecturer at King’s College London and a Gulf analyst, two sides had merely agreed to tone down their hate campaign against each other. Riyadh may take an additional confidence-building measure by opening its air and land border with Doha. However, no compromises had been made on the core issues that spawned the dispute. That raises concern over whether sustainable peace with Qatar can be achieved. But Qatar’s Gulf rivals may have had little choice but to end the dispute because of the incoming less friendly U.S administration under Joe Biden.

“Now that Biden is coming in, there is more pressure on Saudis to show goodwill and show that they are a constructive partner in the Middle East,” Krieg told CNBC.

Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MBS) has come under harsh criticism from Democrats and human rights groups since he ascended to power in June 2017. In just three years, the brash ruler murdered Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, spawned a humanitarian disaster in Yemen, and detained several high-profile activists, businessmen, and senior royals in the kingdom.

According to one advisor to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, MBS sought to repair his image by establishing good relations with the Biden administration. The advisor told the Financial Times that Riyadh’s rapprochement with Doha was intended to be a ‘gift for Biden.” He added that MBS felt threatened following the Democrat’s resounding election victory.

Another analyst who is close to the Saudi ruling family, Ali Shihabi, said that Riyadh has long been trying to resume diplomatic ties with Qatar. “For some time, (Riyadh) has been working on closing many hot files, and clearly this is one,” he told FT.

“The Saudis are being pragmatic here in the same way that the Qataris are pragmatic,” added Krieg. “There is an understanding that a united Gulf front still serves everyone more than spending millions of dollars in trying to undermine each other’s positions.”

United Arab Emirates

The UAE appeared less enthusiastic about making concessions with Qatar to achieve ‘peace.’ The Emirates are led by the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi Mohammad bin Zayed, a man that experts believe instigated the blockade against Qatar. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, an Emirati political scholar who serves as a microphone for the Emirates, tweeted on December 6, 2020, that Gulf reconciliation won’t move ‘one millimeter’ without the blessing and consent of the UAE. Two days later, the Emirates struck a different tone, with one official saying that the UAE appreciates Kuwaiti and the U.S attempts to strengthen Gulf unity. The Foreign Minister of Egypt, which has outlawed Aljazeera from the country, also stated that he ‘hopes these commendable efforts will result in a comprehensive solution that addresses all causes of the crisis.”

A solution that seemed unlikely. Although Doha cut ties with some Muslim Brotherhood leaders in 2014 to put an end to the diplomatic spat with the Saudis and Emiratis, downgrading its relations with Iran or completely closing off communication with non-state groups and Islamists was a bridge too far. Qatar hopes to replace Oman as a dependable mediator between rival sides in the Middle East. According to analysts, the emir is particularly looking to bridge divisions between U.S President-elect Joe Biden and Iran.

It’s all part of Qatar’s foreign policy that attempts to boost its soft power so that it can wield real influence in the region. Becoming a hub for diplomacy is vital to that vision.

This included unofficial and official talks between groups such as Hezbollah and the Lebanese government in 2008, the Taliban and the Afghan government, most recently in 2020, Hamas and Fatah, and Darfur rebel groups and the Sudanese government in 2009, according to Noha Aboueldahab, a fellow at the Brookings Doha Center.

“Severing ties completely with another country has never really been a typical attribute of Qatari foreign policy,” she added.

Qatar’s regional ambitions don’t mean that it isn’t ideologically invested in the Arab world. Beyond acting as a peacemaker, Qatar has supported U.S designated terrorist groups such as Jabhat Al-Nusra in Syria and has backed Islamist political parties across the region.

Meanwhile, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have poured billions of dollars into propping up ruthless tyrants such as Egypt’s Abdel-Fatah Al-Sisi, Libya’s General Khalifa Haftar, and Sudan’s military leaders following the ouster of former dictator Omar Al-Bashir in April 2019. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have long feared that popular revolts could inspire demonstrations in their own countries. Qatar, for its part, refuses to operate as a satellite state of Saudi Arabia. The core issue of the Gulf crisis thus remained the same as it has always been.

End of the Blockade

During the GCC Summit held on 5 January 2021 in al-Ula, a city in the north of Saudi Arabia, Gulf leaders signed a “solidarity and stability” agreement aimed at putting the dispute to bed, labeled the al-Ula declaration. “There is a desperate need today to unite our efforts to promote our region and to confront challenges that surround us, especially the threats posed by the Iranian regime’s nuclear and ballistic missile program and its plans for sabotage and destruction,” said Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who chaired the summit.

Turkey welcomed the step, which stood by Qatar during its blockade.

The move had been anticipated as Saudi Arabia has led efforts to resolve the crisis and helped soften the stance of the other three states involved in the dispute toward Qatar. And on the eve of the summit, Saudi Arabia agreed to reopen its airspace and land and sea borders to its neighbour Qatar, which had been closed since June 2017.

However, the change in sentiment from the four nations is likely down to the changing US administration with President Donald Trump on his way out — someone who has given Saudi Arabia considerable leeway amid morally and legally contentious actions by the kingdom.

Then President-elect Joe Biden, in contrast, warned Saudi Arabia it would not get a free ride under his watch. Washington reportedly urged the disputing nations to come to a resolution, which may help come to a common understanding of Iran.

Analysts, however, note that the reconciliation is far from resolving the crisis. In the immediate term, the move was to allay concerns from the Saudis’ powerful allies while the meat of the agreement is to come later.

It is worth noting that the text of the closing declaration of al-Ula makes no mention of the grievances Qatar had been criticized for: its foreign policy. Therefore, it falls short of securing a stronger, more durable alliance, according to Elham Fakhro, Senior Analyst Gulf States at the International Crisis Group. While affirming the GCC member states’ commitment to achieving the alliance’s principal goals, the declaration does not do much to lessen the intensity of the conflicts in which the Gulf states have played a central role through local allies and proxies, Fakhro writes.

Concessions

There are expected to be concessions on both sides of the dispute, but many do not foresee Qatar will make any.

Political analyst Stéphane Lacroix said that “[Qatar] does not make concessions,” resisting the 2017 demands and making up what it lost through its own means and also by developing new relations.

“Perhaps Qatar will put a little “water in its wine,” but I do not believe it will go further, which means that this crisis will not be completely resolved”, he told RFI in French, while others have also suggested the most Qatar may cede is moderating Al Jazeera or curbing the extent the Muslim Brotherhood can view Qatar as a safe haven.

Qatari foreign minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman, however, said in an interview with the Financial Times that he would not make changes to the network other Arab countries alleged is used to criticise them, nor would it break ties with Iran or Turkey.

“Bilateral relationships are mainly driven by a sovereign decision of the country . . . [and] the national interest”, he told the paper, “So there is no effect on our relationship with any other country.”

Despite the current terms of the agreement still being unknown, there have been hints from Abdulrahman that some outcomes could be positive for Saudi Arabia. It could receive an investment from the Qatar Investment Authority, Abdulrahman indicated, and Qatar could suspend lawsuits filed with the Word Trade Organisation and the International Court of Justice in light of Qatar’s isolation.

Other parties involved in the dispute still have reservations. Lacroix told RFI the boycott was initiated because of the UAE: “In 2015, we saw the two countries forge a sort of extremely tight security pact. In 2017, it was the Emirates that dragged Saudi Arabia into the boycott of Qatar”.

Arguably, tensions between Saudi Arabia and the UAE are growing as the latter starts to carve its own,”n role in the region, exerting its geopolitical relevance. In particular, this can be seen in Yemen, as the two states back different elements of the government led by President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, albeit as part of the same coalition.

Where Qatar is concerned, the UAE, analysts said, is unhappy about its relationship with Ankara. Anwar Gargash, the UAE’s minister of state for foreign affairs, said that this is one of the questions that will come up as the agreement fleshes out.

“One of the big things will be the geostrategic dimensions. How do we see regional threats, how do we see the Turkish presence?” Gargash said, adding that questions will arise on interference in regional affairs through political Islam and Turkey’s presence in the Gulf.

The UAE has outwardly praised the reconciliation, as has Egypt. But like the UAE, Egypt is concerned about resuming relations with Qatar. The Arab Weekly reported that Cairo did not make its stance clear at the summit, and the Egyptian officials spoke in vagaries open to broad interpretation.

The paper’s sources indicate that its concern was to ensure all four parties were satisfied with the deal despite outward support.

Bahrain similarly expressed hope for the deal to be finalized ahead of the summit, despite a row with Qatar along its maritime border. Andreas Krieg from the King’s College London said that the small kingdom was a type of “proxy.”

“While the UAE and Saudi Arabia feel pressure to fall in line with US pressure, they can use Bahrain as a disruptor to continuously show their discontent with Qatar,” he told Al Jazeera.

Qatar appears to have won its hand, refusing to fold despite immense pressure — a unified Gulf serves foreign partners like the US much better after all.