Introduction

The overthrow of the Gaddafi regime was organized by a self-appointed National Transitional Council (NTC), which provided the political leadership in the struggle. Originally based in Benghazi, it moved to Tripoli after the fighting was over and took charge as an interim government until the elections of July 2012. The NTC’s main challenges were imposing order, disbanding the former rebel forces, rebuilding the economy, creating functioning institutions, and managing the transition to democracy and the rule of law. During this period Abdurrahim al-Keib (appointed 1 November 2011) was elected interim Prime Minister by the National Transitional Council (NTC).

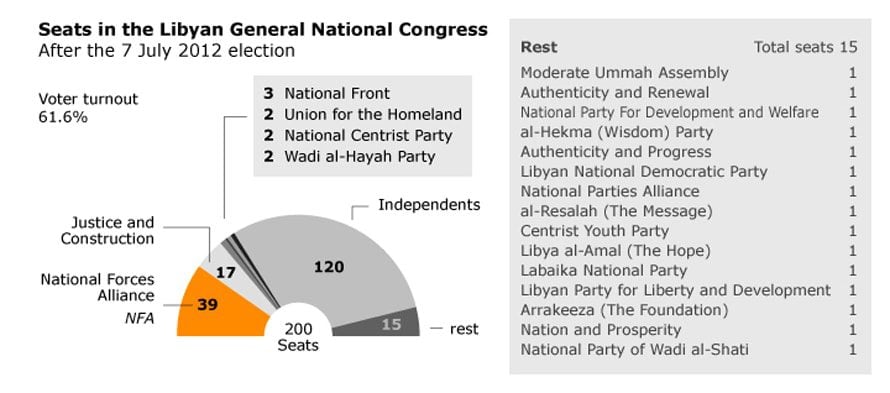

The NTC oversaw elections in July 2012 that were Libya’s first free national elections in six decades. Members of the NTC and the old Gaddafi government, including their relatives, were barred from running. Voters elected a 200-member assembly, the General National Congress, to replace the NTC, which was dissolved.

The Presidency

The president of the General National Congress (GNC) is considered the de facto head of state. Mohammed al-Magariaf, Libya’s ambassador to India in the 1970s and currently leader of National Front Party, was elected to this position on 10 August 2012. He served until May 2013 when he was urged to resign in accordance with a new ‘isolation law’ prohibiting officials from the Gaddafi regime from holding public office. He was succeeded by his deputy, Juma Atigha, until 25 June 2013, when the GNC elected Nouri Abusahmain, who is said to have had the backing of the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Justice and Construction Party. On 6 April 2016, Abdulrahman Asswehly was elected as chairman of the High Council of State.

The Executive

Libya has faced a political crisis at the executive branch level since elections for the House of Representatives (HoR) in June 2014. Following the crushing defeat of the Islamic parties, which obtained only 23 seats, the newly formed Libya Dawn coalition, dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, seized control of the capitol in Tripoli in the west and forced the elected and internationally recognized HoR, led by Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thinni, to flee to Tobruk in the east.

In November of that year, a ruling by the Supreme Court in Tripoli declared the HoR illegal and unconstitutional. This further confused the legitimacy of the warring sides, and was ignored by the al-Thinni government and its international backers.

On 17 December 2015, after a year of negotiations, representatives from the country’s rival factions signed a United Nations-brokered political agreement to form a single Government of National Accord (GNA). Under the agreement, a nine-member council would form a government, with the eastern-based HoR as the main legislature, and a High Council of State as a second, advisory chamber. The government, headed by unity Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj, was named a month later, but both Tripoli and the rival administration in Tobruk were reluctant to acknowledge its authority.

The Legislative

The elections of 7 July 2012 for a General National Congress (GNC) were the country’s first free national election in six decades. The members of the GNC were elected through a dual voting system: eighty seats were chosen in twenty constituencies by proportional representation, under a party-list system, and 120 seats from 69 multiple-member constituencies. In the list constituencies, parties were obliged to alternate their ordering between men and women to ensure adequate representation for women.

In the elections of July 2011 two parties did well: the National Forces Alliance (NFA), a liberal alliance led by Mahmoud Jibril, the wartime rebel Prime Minister, took 39 out of the 80 party-list seats, and the Muslim Brotherhood–oriented Justice and Construction Party (JCP) took seventeen seats. Minor parties were the National Front Party, with three seats, and the National Centrist Party and Union for Homeland, and the Wadi al-Haya Party for Democracy and Development, each with two seats. Fifteen other parties each won one party-list seat.

The multi-member seats all elected independents who did not openly state their affiliations, although in the elections for Prime Minister, they secured the election for Mustafa Abushagur rather than Mahmoud Jibril in the second round of voting. Abushagur was, however, not sworn in because the GNC did not approve his proposed cabinet proposals, which had excluded the NFA. On 7 October 1912 he was removed from office by the Congress. On 14 October 2012 the GNC appointed Ali Zeidan Prime Minister, and, after it had approved his cabinet, he took office on 14 November 2012.

Zeidan’s priorities are to reinstall central authority, build up functional security institutions, enact a meaningful reconciliation process, improve the health care and educational systems, rebuild infrastructure, and create employment.

In April 2016, the Constituent Assembly of Libya confirmed the completion of a draft of the Libyan constitution. The draft is founded on the principles of the unity of Libya as a republic, respect for human rights and the rule of law, equality, good governance and the peaceful transition of power.

At the legislative branch level, the draft constitution contains a paragraph pointing to the formation of a Shura Council consisting of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The Shura Council has the authority to enact legislation, affirm the general policy of the state, the general plan for economic and social development and the general budget, in addition to supervising the work of the executive branch.

The 2014 parliamentary elections saw the Islamists lose out to the liberals, which sparked the political crisis that is still dividing the country.

The Judicial

After the revolt against the Gaddafi regime began, the National Transitional Council (NTC) declared that respect for the rule of law and the establishment of an independent judiciary were immediate priorities.

The NTC changed the role of the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC), the managing body of the court system, to make it more independent of the government, and the SJC set up a Judicial Reform Committee in June 2012. In practical terms, however, this amounted mainly to a change of personnel rather than a radical reform of the legal system.

Gaddafi had largely preserved the basic structure of the legal system that was set up under the monarchy, although he introduced several special tribunals. The NTC abolished these but otherwise kept the structure in place.

This had four levels:

- Summary courts (sometimes referred to as partial courts), in most small towns, where a single judge heard cases involving misdemeanours. Except in very minor cases, the decision could be appealed.

- Courts of first instance, in the governorates. These heard appeals from summary courts and had original jurisdiction over larger cases. They consisted of a panel of three judges, ruling by majority decision, and heard civil, criminal, and commercial cases. They applied Sharia law to personal and religious matters.

- Appeals courts: there were three courts of appeal (in Tripoli, Benghazi, and Sabha). A three-judge panel, ruling by majority decision, heard appeals from the courts of first instance. These courts had original jurisdiction in felonies and high crimes.

- The Supreme Court was located in Tripoli. There were five chambers: civil and commercial, criminal, administrative, constitutional, and Sharia, with a five-judge panel in each chamber, ruling by majority. The court was the final appellate body for cases emanating from lower courts.

Although the structure has not been changed, there has been much debate about whether individual judges should be removed because of their close association with the former regime, the extent to which the Sharia should be applied, and the conduct of trials of former regime officials.

In the case of the most prominent members of the Gaddafi regime and those accused of crimes against humanity who are now under Libyan control, there have been further arguments about whether they should subject to Libyan jurisdiction or to that of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

For example, in the case of Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, Muammar’s son, there has been a dispute over whether he should be tried in Zintan, where he was first imprisoned, or in Tripoli, or outside the country under the jurisdiction of the ICC. At a lower level, courts were impeded by disorder and the wide availability of weapons and consequent fear of retaliation, and by reports of widespread corruption.

The International Crisis Group reported that, for the first year after Gaddafi was removed, criminal courts barely functioned, and in some outlying areas, such as the Jebel Akhdar, courts did not function at all. By May 2012, civil trials in Tripoli began to be held regularly, but few criminal cases made it to trial.

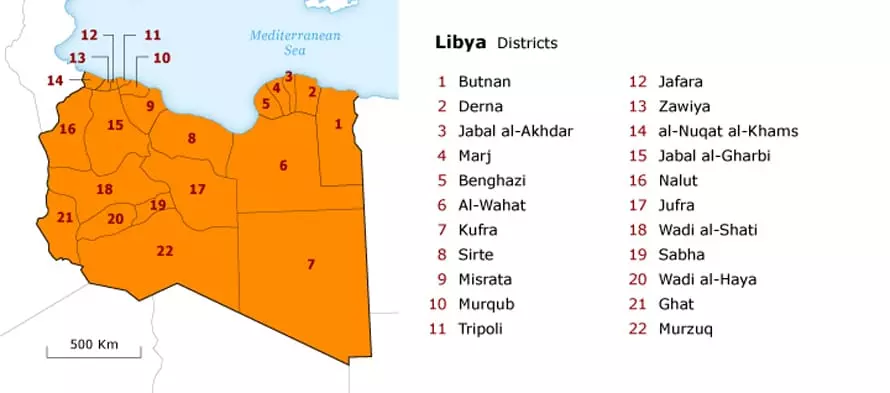

Local Government

Libya has 22 districts, called shabiyat: Butnan, Jabal al-Akhdar, Jabal al-Gharbi, Jafara, Jufra, Kufra, Marj, Murqub, al-Wahat, al-Nuqat al-Khams, Zawiya, Benghazi, Derna, Ghat, Misrata, Murzuq, Nalut, Sabha, Sirte, Tripoli (Tarabulus), Wadi al-Haya, and Wadi al-Shati.

Political Parties

Many political parties were set up after the end of the 2011 revolt.

The major political parties in Libya

The National Forces Alliance (Tahaluf al-Quwa al-Wataniya) (NFA)

An alliance of many smaller organizations and independents that was set up in February 2012. It is led by Mahmoud Jibril, who described it as a ‘moderate Islamic movement that recognizes the importance of Islam in political life and favours Sharia as the basis of the law’ (Libya Herald 1 July 2012). Some Western commentators have described it as liberal, though a German report in May 2013 characterized it as an ‘unideological rallying point for parts of the establishment’. It fielded 70 candidates and won 48 percent of the votes and 39 seats in the 2012 elections.

Justice and Construction party (Hizb al-Adala wa-al-Bina) (JCP)

The political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood in Libya, led by Mohamed Sowan. It was officially founded on 3 March 2012. It fielded 73 candidates and won 10 percent of the vote and 17 seats in the 2012 elections.

The National Front Party (Hizb al-Jabha al-Wataniya)

The successor to the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL), was one of the main resistance organizations to Gaddafi; it was set up in 1981. The NFSL was dissolved in May 2012, and its leader, Mohamed Magariaf, became the leader of the new party. It claims to be a liberal and progressive party that seeks to empower women in the political process. It fielded 45 candidates and won 4 percent of the vote and 3 seats in the 2012 elections.

Union for the Homeland Party (al-Ittihad min ajl al-Watan)

A Misrata-based party led by Abdurrahman al-Swehli, the grandson of Ramadanal-Swehli, who helped found the Tripolitanian Republic in 1918. It fielded 60 candidates and won 4 percent of the vote and 2 seats in the 2012 elections.

National Centrist Party (Hizb al-tayyar al-watani al-wasati)

Led by interim oil minister in the National Transitional Council, Ali Tarhouni. It was launched in October 2011. Tarhouni described the party as fundamentally moderate: ‘Moderation is the name of our movement. We are moderate. We are in the middle. I think any radicalization of Islam is something that we oppose.’ It won 4 percent of the vote and 3 seats in the 2012 elections.

Homeland Party (Hizb al-Watan)

Had the former emir of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and former head of the Tripoli Military Council, Abdelhakim Belhadj, amongst its members, fielded 59 candidates and was believed to be popular with former revolutionary fighters, but it failed to win a single seat in the 2012 elections.

The formal party representations appear low because they result from the formal lists that the parties presented in the elections. Each of the parties can call on the support of blocs of independents. A German research report of 2013 estimated that there were only 55 ‘genuine’ independents.

Amongst the remaining independent elected members, 25 were associated with the NFA and 17 with Justice and Construction, and 23 were Salafis or associated with other party lists (Wolfram Lacher, ‘Fault Lines of the Revolution Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya’, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 2013).

Before 2011

Before 2011 all political parties were banned. The only condoned criticism of public affairs came from Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam, who made speeches advocating change. Civil and political rights were very limited. The Arab Human Development Report 2004 noted that the call for reforms came mainly from Libya’s opposition abroad, which consisted of exiles and politically active refugees, drawn from disparate groups of monarchists, former diplomats and ministers who had defected, journalists, and students. The largest groups of Libyans abroad live in Great Britain and the United States. There are also communities in Italy, Tunisia, and Egypt. The most important exile group was the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL), formed in 1981 and led by Mohamed Magariaf. It was supported by the United States and Saudi Arabia.

In 2005 the NFSL joined six other groups to form the National Conference for the Libyan Opposition. From 2005 an underground opposition movement called Khalas (End it!) appeared in Libya, modelled on the Egyptian Kefaya (Enough) movement.

Although opposition inside Libya was quashed harshly and effectively, it grew steadily in the eastern region from the 1980s onwards, partly out of dissatisfaction with the socio-economic marginalization of Cyrenaica (Barqa) region.

A common rallying-point for Gaddafi’s political opponents was Islam. This stream in political life goes back to the 1950s, when King Idris offered sanctuary to members of the Muslim Brotherhood who were fleeing Nasser’s rule. Many taught at Libyan universities and built up a strong student following. After Gaddafi disbanded the Muslim Brotherhood, it operated in exile and underground. One offshoot was the Libyan Islamic Fighting group (LIFG), which put up the only armed opposition to the Gaddafi regime. It was founded in in 1995 by Libyans who had fought in Afghanistan against the Soviet forces, including Abdelhakim Belhadj, Noman Benotman, Abu Yahya al-Libi, and Abu Laith al-Libi. It aimed to establish an Islamic state in Libya. In 1996, when it was allegedly funded by the British intelligence agency MI6, it attempted to assassinate Gaddafi, but after the 9/11 attacks, the UN 1267 Committee listed the LIFG as a terrorist organization, although it was not until 2005 that Ayman al-Zawahiri and Abu Laith al-Libi announced it had joined al-Qaeda. Noman Benotman rejected this approach and eventually joined in the campaign against it.

The LIFG was heavily repressed inside Libya, and many people were arrested on the grounds that they were members. In 2008, 90 members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group were released, apparently as part of the efforts of Saif al-Islam Gaddafi to project himself as the leader of a political opening. A further two hundred were released in March 2010, including Abdelhakim Belhadj, who had been returned to Libya under the US rendition programme in 2004 and severely tortured.

Rise of Islamists

After the 2011 revolution Islamists organized openly, soon gaining much credibility from never having previously taken part in politics in Libya. By 2012 two Islamic-oriented political parties emerged, the Justice and Construction Party (considered the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, despite its leaders’ denials), and the Homeland Party, which is led by two former political prisoners, Ali al-Sallabi and Abdelhakim Belhadj. There is a smaller group, not organized into a party, centred on the grand mufti Sheikh Sadeq al-Ghariani.

Corruption

The Corruption Perception Index 2003 of Transparency International qualifies Libya as the most corrupt country of all Arab League member-states. In the Corruption Perception Index 2012 Libya ranks 160 out of 174 countries, with a score of 2 out of 10 (0 is highly corrupt). The Corruption Perceptions Index ranks countries/territories based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be. It is a composite index, drawing on corruption-related data from expert and business surveys carried out by a variety of independent institutions.

The Libyan Investment Authority (LIA) was a government-managed fund and holding company under the Gaddafi regime. It was established in 2006 under the aegis of Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and managed investments in agriculture, real estate, infrastructure, oil and gas, and shares and bonds. Its purpose was to manage the oil-revenue surplus, and it took over the assets of the Libyan Foreign Investment Company (Lafico), established in 1982, and Oilinvest, founded in 1988. Lafico had interests in Barclays Bank, Banca di Roma, Citigroup, Corinthia Bab Africa Hotel, Fortis, the Juventus football club (in Turin), Tamoil, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, J.P. Morgan, and HSBC bank.

In June 2010, the LIA held USD 53.3 billion in assets, a decrease of 4.5 percent from the end of the first quarter that year, when total assets were USD 55.9 billion. An unusually high proportion of the portfolio (around USD 19.8 billion) was held in cash deposits, and its stock of equities was valued at USD 5.2 billion, making up 9.8 percent of its total portfolio. Both the cash holdings and the equity were losing value in a falling market, but also because of the low calibre of its employees, many of whom were friends and associates of the Gaddafis.

In 2011, Ali Tarhouni, Minister of Financial and Oil Affairs for the National Transitional Council, appointed Mahmoud Badi, formerly a civil servant under Gaddafi, to investigate the Libyan Investment Authority. In August 2011, Badi found ‘misappropriation, misuse, and misconduct of funds’, with USD 2.9 billion missing from the LIA.

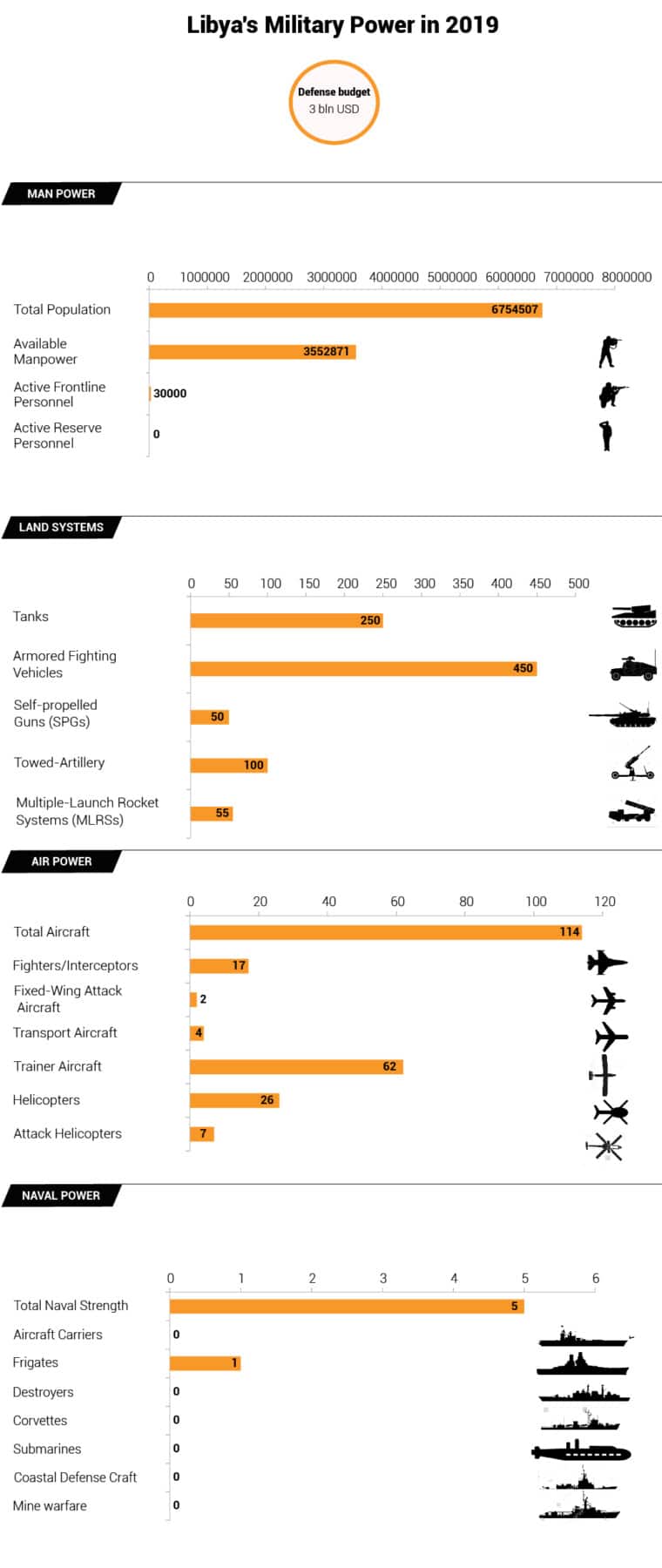

The Military

Still reeling from the aftermath of civil war following the Arab Spring, Libya remains an unsettled and divided country with two competing governments.

In 2019, Libya is ranked 77 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 118,748 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $3 billion. In 2014, Libya’s military expenditure accounted for 15.5 per cent of GDP, compared with 7.6 per cent in 2013, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. More recent numbers are unavailable.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 30,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 30,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 118 | 66 |

| Fighter aircraft | 20 | 52 |

| Attack aircraft | 20 | 57 |

| Transport aircraft | 5 | 49 |

| Total helicopter strength | 27 | 68 |

| Flight trainers | 63 | 42 |

| Combat tanks | 300 | 54 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 530 | 77 |

| Rocket projectors | 75 | 38 |

| Total naval assets | 5 | - |

Libya’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

The 2013 edition of The Military Balance provides a picture of a Libyan military in disarray. Not only is the government’s control over the militia brigades uncertain, but the state of the armed forces is essentially unknowable. Some of the Gaddafi-regime’s weaponry was destroyed in the fighting, but the distribution of the rest is uncertain. It is possible to estimate the remaining warships and land forces, although many of the latter were destroyed early in the campaign.

In late 2011, the New York Times estimated that the Libyan navy had one operational frigate, one operational corvette, one operational and one decommissioned minesweeper, and one decommissioned submarine (ex-Soviet Foxtrot class).

The Gaddafi-era Air Force was almost completely destroyed. In June 2012 the Air Force chief-of-staff, Saqr Geroushi, announced that he was seeking to re-equip with Eurofighter Typhoons; the British embassy refused almost immediately to confirm that, although it did say that Britain was assisting with the restructuring of the Armed Forces. In July 2013 the British government and, after the G8 Summit in July 2013, Britain, France, Italy, and the US promised a defence and security package to assist Libya, and the British government announced a training programme for 2,000 Libyan soldiers.

A major effort has been put into equipping the navy and coast guard with small inshore patrol boats: thirty French-built semi-rigid boats were delivered in May 2013, part of an order for fifty, to be used to patrol ports and installations.

The Navy has also acquired Dutch-made patrol craft and is reported to be purchasing 25 South Korean patrol boats for the coast guard. Naval training has been provided by Britain, France, and Malta (in air-sea rescue).

In 2010 the available manpower for military service was 1.8 million males and 1.7 million females in the 16-49 age group. It was estimated that the manpower fit for military service is about 300,000 men and women less than this.

In January 2017, Russia reactivated a $2 billion deal to arm Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, leader of the eastern-based parliament in Tobruk. The deal, which was originally signed in 2009, includes ten Sukhoi Su-30 and ten Su-35 fighter planes, six Yakovlev Yak-130 training planes and Project 636 Kilo Class submarines.

Security

Plundering in Benghazi, October 2013 / Photo HHCentral authority in Libya is weak after the 2011 revolution, although Prime Minister Zeidan has pledged to make security the top priority. A graphic demonstration of this weakness came in October 2012, when armed militiamen, thuwwar, stormed the hall of the General National Congres (GNC) in Tripoli during voting to confirm Zeidan’s government. They objected to six of his cabinet choices. Threats also come from outside the country, particularly following the French-led military invasion of Mali. This led, in turn, to cross-border raids by splinter groups of Ansar al-Sharia.

The main internal problem lies with former revolutionaries who maintain their separate militias in order to pursue their political ends, rather than relying on elected representatives.

The rebellion against the Gaddafi regime grew piecemeal, and, as the rebels spread into the hinterland, they established local military councils that co-opted the residents to manage affairs in the absence of a functioning army and state. Local military brigades then emerged, nominally in allegiance to the National Transitional Council (NTC) but, in practical terms, autonomous. Some of these local brigades pursued local political agendas, while others were infiltrated by criminals and did not surrender their weapons. These developments worried both the fledgling government and the principal coalitions of revolutionary fighters, who were worried by the spread of uncontrolled armed groups and by the government’s inability to deal with them. They therefore retained control of their weapons rather than demobilizing. During the fighting, the revolutionary brigades had coalesced, for example, the Revolutionary Brigades Coalition in the east and the Misrata Union of 17 February Revolutionaries in the west. After the final collapse of the Gaddafi regime, they formed the de facto Libyan army. Although they maintained their local affiliations, they eventually began to cooperate on a wider scale. Zintan came under the control of a coalition of military groups in late 2011, but Tripoli remained fragmented between the Tripoli Military Council, led by Abdelhakim Belhadj, and the Tripoli Brigades. But this consolidation could not continue into integration with the army, which was under-equipped and tainted in the eyes of the revolutionaries by its association with Gaddafi. As a result, the brigades sought a parallel system in which they could continue to function. The Libyan Shield Forces (LSF) were designed achieve this.

The LSF nominally answered to the army chief-of-staff, which gave them legitimacy, but they acted with considerable autonomy. They were deployed first in Kufra in March 2012 and were able to impose a ceasefire in localized fighting in Sabha in April. The structure quickly spread across the country as an auxiliary army acting in the name of the government but representing the political interests of the revolutionaries who had fought the civil war. The leadership was formalized as a High Commission in May 2102, but it was not always successful: it found the fighting in Zuwara especially difficult to control.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Libya’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: