Introduction

Yemen’s political system is complex and sometimes paradoxical. As always, alliances depend on many factors. In Yemen, the situation is complicated by the strong position of the tribe (qabila), which always looks out for its own tribal (and often conservative) interests.

The tribe can be regarded as a network of kinship relations reaching far beyond the nuclear family.

Backed by a strong tribal base, former President Ali Abdullah Saleh proved a master at balancing the country’s powers through a mixture of patronage, co-optation, changing alliances, throwing opponents off balance, and outright repression.

By positioning himself as a mediator or dealmaker between Yemen’s various factions, Saleh held the country together in relative peace but also created non-transparent governance, widespread corruption, and nepotism. This seriously undermined a proper functioning of the political institutions. All this has proved unfavourable for progress, investment, and innovation.

The Arab Spring

This led to a major popular uprising in the Arab Spring of 2011, in which many of the tribes left Saleh’s coalition, and civil war loomed. In June 2011, Saleh was wounded in a bomb explosion on the presidential compound and received treatment in Saudi Arabia.

Several weeks after his return to Yemen, Saleh signed an agreement to step down and leave office after early presidential elections had been held in February 2012.

The Presidency

Ali Abdullah Saleh became President of what was then called North Yemen (Yemen Arab Republic, YAR) in 1978. Saleh’s position in Yemen was for a long time more or less undisputed. As a northern tribesman, Saleh received support from the central and northern tribes, as well as from the urban bourgeoisie. Saleh’s strongest base was the army, from which he rose as an officer (colonel), to become President in 1978.

Saleh initially enjoyed wide popular support throughout the country, although he was always less popular with southerners than with his fellow central and northern countrymen. From the outside, Yemen looked like a Western-style democracy, but power and wealth were, in reality, distributed through an intricate and non-transparent system based on the inclusion of as many ‘elites’ as possible.

These elites, whether based on religion, tribe, economic and business power, regional influence, technocratic and scientific influence, or grass-roots popular support, were awarded positions and other opportunities within the regime, as long as they supported Saleh. By offering broad access to power, Saleh made those elites both dependent on and accomplices of his pyramid system of redistribution of wealth and power.

This seemed a continuation of deeply rooted patterns of power sharing, practised by most rulers throughout Yemen’s history. In hindsight, however, Saleh’s shura was badly executed, as his objectives proved to be geared too much towards personal enrichment of those within the ruling pyramid, fostering the development of large-scale corruption and devastating Yemen’s economy.

Atop the pyramid sat Saleh himself, surrounded by members of his clan – sons and nephews –, who in turn were surrounded by other members of his Sanhan tribe. All of those in the first circle occupied key positions in the large and dominant, though fragmented, Yemeni army. Elites from all pockets of society could find footing in all other levels of the pyramid, providing themselves and their relatives with high positions and ample business opportunities. With divide-and-rule tactics, Saleh made sure no elite, individual, or collective garnered enough power to disturb the accumulation of wealth and power at the highest level.

Former President Saleh was twice re-elected, in the elections of 1999 and 2006, both times with an absolute majority (97 percent and 78 percent, respectively). After the 1999 elections the Parliament passed a law extending presidential terms from five to seven years. In the 2006 election, the main opposition party, Islah, joined the united opposition in supporting an alternative candidate, who subsequently received nearly a quarter of the vote.

During his last term as President, the opposition accused Saleh several times of wanting to run for a fourth seven-year term, which would require changing the Constitution. Saleh repeatedly denied those accusations as well as claims that he was grooming his son Ahmed as his successor (who will reach the age of forty in 2013, the age required by the Constitution in order to become President).

Several weaknesses undermined this pyramid system. The primary weakness of the system was its goal: the accumulation of wealth by the elites, rather than the development of Yemen as a whole. This proved unproductive in general, which resulted in the cake and its slices growing ever smaller. Another weakness was the narrowness at the top, where only Saleh’s blood relatives found a place; this gave rise to ill feelings among those influential people who had been properly consulted throughout Yemen’s history but were now largely and increasingly neglected, receiving only a small share of the profits.

Another major weakness was that the elites became increasingly detached from the group they represented; only elites benefited, while society as a whole saw their opportunities hampered. A last weakness consisted of two groups that Saleh could not incorporate into his system: the Houthis and the Southern Movement.

The Houthi movement (al-Ḥuthiyun) consisted of marginalized northerners, followers of Hussein Badr Eddin al-Houthi, who started an uprising, evolving into guerrilla actions from 2004 onwards. These wars were increasingly costly and violent.

From 2007, the ever more vocal Southern Movement (al-Harik al-Janubi) developed in the south. The movement consists of former civil servants, but also neglected southern tribes and others. They all point to a process of increasing political and economic marginalization of the South since the war in 1994 – and, in general, of domination of the South by the North.

Around 80 percent of Yemen’s oil revenues comes from the oilfields in the South, but were mainly used to finance a system which, under Saleh, became based more than ever on patronage and co-optation. Over the years protests in the South have been met with repression; prominent leaders and activists have been harassed, beaten and arrested. As a result demands for decentralization gradually have been replaced by calls for secession.

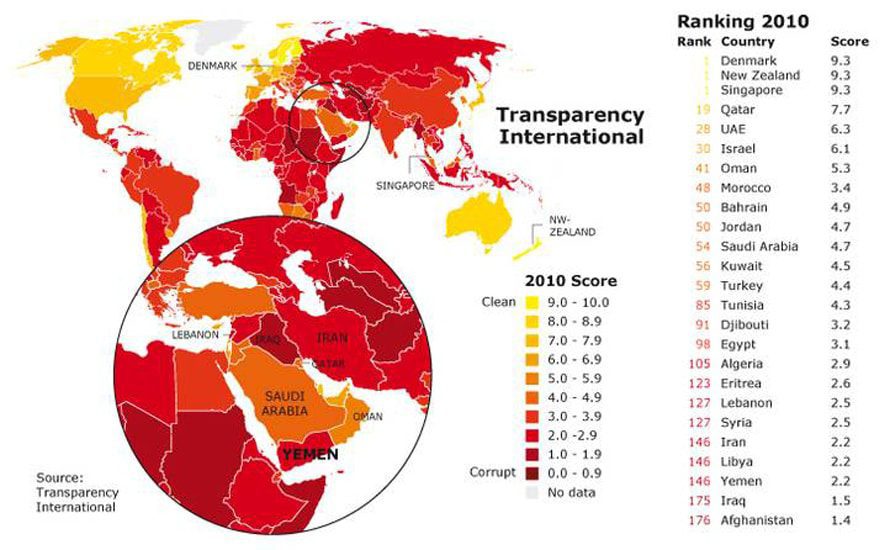

In the run-up to the collapse in 2011, Yemen was repeatedly warned about its level of corruption, which had always been widespread. In 2010 Transparency International rated Yemen 142nd on al global list of 178, down from 137th in 2007, with a score of 2.2 (out of 10), down from a score of 2.5 in 2007 and 2.7 in 2004.

In March 2011, under the influence of a popular uprising which was in turn brought about by the so-called Arab Spring in Egypt and Tunisia, these destabilizing factors proved too strong, and the pyramid collapsed. In June, Saleh was wounded in a rocket attack, receiving treatment in Saudi Arabia.

In November 2011, Saleh signed an agreement to step down, promising to leave office. Saleh transferred his presidential powers to the Vice-President, Hadi, who was to take care of state issues for a period of 90 days, until the early presidential vote in February 2012, in which Hadi was sole candidate. Hadi took oath of office on 25 Febrary 2012 and is now President of Yemen.

Shura

Majlis al-Shura, the Yemeni Parliament Shura (consultation) is an important institution in tribal affairs, which was incorporated into political Islam and is the Islamic equivalent of consultative democracy. The rulers of the state are supposed to consult those with knowledge and authority on important decisions.

Rulers of Yemen have practised shura throughout history, thus ‘cementing the country’s unity’. Some analysts say this has, in modern times, prevented Yemen from becoming a failed state like Afghanistan or Somalia. When rulers, such as the last imam (who ruled for six days), did not practice shura, their rule was short-lived.

The current, formal Majlis al-Shura (Council of Consultation) came into being with the constitutional change of 2001. The Majlis al-Shura consists of 111 members, all of whom are appointed by the President.

As tradition dictates, seats are held by sheikhs (tribal leaders), qadis (judges), and sayyids (descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, often regarded as learned men). Constitutionally, the Majlis al-Shura has an advisory role.

Drafts and proposals are passed through the Shura before Parliament votes. The Shura can also have a decisive voice in certain important legislative matters. As its members are appointed, its role and function are not always transparent.

The Executive

After becoming President in 1978, Ali Abdullah Saleh headed various governments through his General People’s Congress (GPC). The GPC has dominated Yemeni politics since its founding in 1990, making Yemen virtually a one-party state.

After unification, in 1990, North Yemen’s GPC shared some power with South Yemen’s (PDRY) dominant socialist party YSP during a transitional period which lasted until the planned general elections of 1994.

Shortly after the YSP suffered heavy losses in the 1994 elections – the population of North Yemen is about five times as large as that of South Yemen –the South announced its secession from the union. However, the attempt to break away was crushed by the North in a short but tough civil war.

After the 1994 elections, Saleh’s GPC formed a broad coalition with the Islamist Islah (Reform) party, the strongest opposition party. The GPC has headed the government alone since the elections of 1997 and 2003, while still appointing opposition candidates of YSP and Islah to some ministerial posts or as chairmen of one of the houses of parliament.

The last cabinet of Saleh’s rule had a technocratic character, with young, foreign-educated technocrats holding key posts. This has been seen as a measure emphasizing Yemen’s ambition to become a modern state with solid institutions, a transparent bureaucratic infrastructure, and a stable state budget, favouring much-needed foreign investment. The presence of two female ministers in the cabinet was viewed in a similar light. Transparency and modernity were, however, largely superficial, and real power remained in the hands of Saleh and his close relatives.

The Legislative

Yemen may be the poorest and least developed country of the Middle East, but it boasts the longest tradition of ‘Western-style’ democracy in the region. The Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) held elections even before unification.

Yemen has an elected unicameral parliament, the Assembly of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwwab), with 301 seats. Elections in unified Yemen have been judged to be ‘reasonably’ free and ‘partly fair’, although obscure negotiations and corruption have always played a large role. Parliamentary elections were held in 1993, 1997, and 2003, with a turnout of 76 percent (six million people) in 2003, which dropped to 65 percent in the presidential elections of 2006.

Former President Saleh’s political party, the General People’s Congress (al-Mutamar al-Shabi al-Amm, GPC), has dominated the 301-seat parliament since its founding in 1990, taking an ever-increasing majority of the vote. However, this majority is obscured by the large number of‘ ‘independent’ candidates, who are often brought into the GPC-coalition after being elected.

Parliamentary elections scheduled for April 2009 were postponed for two years, because of what the ruling GPC called a ‘political crisis’, following the announced boycott of the elections by the opposition.

Political Parties

General People’s Congress (GPC)

Formal Yemeni politics were dominated by the General People’s Congress (GPC) until 2011. It won all of the elections and each time formed the government. A large number of factions are represented in the GPC, urban as well as tribal.

The GPC lacks an ideology and a clear-cut political program, almost resembling, in that respect, a shura. After the last three elections, many independents joined the GPC upon being elected.

Members of the opposition also sometimes join the GPC, as it is almost the only way to exert influence in Yemeni politics.

Islah (Reform)

The foundation of the main opposition party, the Yemeni Congregation for Reform (al-Tajammu al-Yamani li-al-Islah), commonly known as Islah (Reform), is tribal, but the doctrine is conservative Islam.

Islah can be described as a Muslim brotherhood in Yemen, as it advocates Islamic principles and opposes, as do many others, the widespread corruption in government.

The immediate reason for its formation was a fear of secular influence on the government after the union with Marxist South Yemen. Salafis (Orthodox Muslims) belong to its constituency as well.

Islah holds a special position in the political landscape, thanks to its leader Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar, who died in 2007. Al-Ahmar was the long-time sheikh of the Hashid, the most powerful tribal federation.

Under al-Ahmar’s leadership, Islah first allied itself with Saleh’s GPC. Islah and al-Ahmar also supported Saleh in all but the most recent presidential elections. In 2005, Islah allied itself with a group of opposition parties, called the Joint Meeting Parties (JMP).

Since al-Ahmars death his eldest son, Sadiq, heads the tribal federation of Hashid, while his brother Hamid heads Islah. Hamid is one of the strongest candidates in the race to become Yemen’s next president. The al-Ahmars are reputed to have a kind of domestic ’embassy’ in Sanaa.

Puritan and Moderate Wings of Islah

There is another face to Islah, that of Abdul Majeed al-Zindani. Al-Zindani represents puritan Wahhabi (or Salafi) Islam, which originated in Saudi Arabia.

The Saudis have financed the establishment of so-called ‘scientific centres’ throughout Yemen, where young people are educated according to Wahhabi beliefs. It has been reported that students who attend classes at these institutions are offered financial rewards, which helps to make Wahhabism a more popular form of Islam than traditional Zaidi Shiism.

Al-Zindani is a controversial figure, who has been tied to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda in Western media reports. It is unclear which of the two factions – the tribal al-Ahmar faction or the puritan Salafi faction – has dominated the party since al-Ahmar’s death.

A third important figure in Islah is Mohammed Qahtan, the official leader of Islah and spokesman of the JMP. Qahtan represents the more moderate wing of the Muslim Brothers within Islah but is not expected to play an important role in the future.

Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP)

The Yemen Socialist Party (al-Hizb al-Ishtirakiya al-Yamaniya, YSP), a remnant of the former socialist state of South Yemen (PDRY), enjoyed strong southern support just after unification but lost popularity because of internal strife and the war of secession of 1994.

The party has remained popular in Aden but does not enjoy much support elsewhere. Its current secretary, Yasin Said Numan, however, enjoys widespread respect and is likely to play a role in the post-Saleh era.

Numan is also the official leader of the Joint Meeting Parties.

Joint Meeting Parties (JMP)

The Joint Meeting Parties (Ahzab al-Liqa al-Mushtarak, JMP) is an umbrella organization formed in 2005 uniting the two main opposition parties in Yemen, the Islah and YSP, plus three minor parties: al-Haq, the Unionist Party, and the Popular Forces Union Party.

In the 2006 presidential election the JMP backed a common candidate opposing long-time President Saleh, rallying a surprising 22 percent of all votes for Faisal bin Shamlan.

Scope of Government

Most tribesmen carry arms, as a sign of independence and resilience: a pistol in the back pocket, a Kalashnikov hanging over the shoulder, and the janbiya (a curved dagger) hanging from a broad, colourful belt.

In the past several decades, the Dar al-Salam Organization, which works for disarmament, has proved successful in eliminating the carrying of arms in the main cities. Guns and pistols have more or less disappeared, and the janbiya has been promoted to traditional dress – although it is still being carried.

The reach of Yemeni government does not, however, usually extend into its border regions. In many areas the tribes are still autonomous.

In tribal country one frequently comes across patrolling heavily armed pick-up trucks. Tribes traditionally block roads, in order to extort government funding, or take people hostage, to pressure the government into funding roads, schools, and medical facilities in remote areas. Several tourists have been taken hostage in the last two decades and a large part of Yemen is off-limits to tourists.

In areas of eastern Yemen, where the major oilfields are located, the army regularly fights tribal groups demanding a larger share of the oil revenues. In the south, more specifically in the province of Abyan, an uprising of Salafis (Orthodox Islamists) began in 2010 and developed into a war around the cities of Zinjibar, Hawta, and Jaar.

In press reports these militants were often referred to as AQAP (al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula), de-emphasizing the role of other Salafi and tribal groups in the fighting.

Tribalism

In tribal societies decisions are taken in the interest of the family, but this extends well beyond the nuclear family, encompassing a large group of people sharing a supposed common ancestor, subdivided into tribes and clans with ancestral offspring.

Identity is therefore not only individual but also strongly tribal. Accordingly, an insult directed at, or a pledge made by, a member of a tribe can be taken personally by a distant member of the same tribe.

Marriage occurs within the tribe, thus ensuring that (land) ownership remains within the tribe. The tribal sheikh (leader), whether chosen or hereditary, represents the tribe in inter-tribal matters. (In such matters, non-tribal sayyids – descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, often regarded as learned men – sometimes play an important role).

The sheikhs are supposed to be consulted by the rulers of the state in matters concerning the tribe’s territory.

The northern mountains and the eastern plateau have remained largely free of outside influence. Throughout the centuries, the tribes ruled themselves in constantly varying alliances. At times they extended their rule southwards.

Dominant throughout Yemen’s history have been the tribes of Hamdan, who trace themselves back to Kahlan. Their territories lie in the heartland, north and east of Sanaa.

The Hamdani tribes are divided into two confederations, the Hashid and Bakil (the so-called ‘two wings of the government’).

The former President, Saleh, is a member of the tribe of Sanhan, which belongs to the Hashid. As a result, the tribes of Hashid, although fewer, dominate the government, but the government does not control the tribes: sometimes it is, in fact, the other way around – many of them are still autonomous.

The powerful Hashid and Bakil are spread across the mountainous heartland, from Saada to Ibb. Beyond Ibb, the tribes belong to the less coherent and less powerful confederation of Madhaj, which also includes the tribes from the Hadramawt.

The peoples of the Tihama are also tribal, but they do not belong to a confederation; they are called Zaraniq (singular, Zarnuqi).

Foreign Policy

Yemen is of minor geopolitical importance to the rest of the world. The port of Aden and its control of the Bab al-Mandab, the narrow strait at the southern end of the Red Sea, have attracted strategic interest from naval powers throughout history. The rest of the country remained relatively isolated from the outside world until the end of the imamate, in 1962. Yemen has, since then, been a strong advocate of the Arab cause.

In the 1990-1991 Gulf War, Yemen took a neutral stand, stressing an Arab solution to the conflict. This was interpreted by members of the US-led so-called coalition, of which Saudi Arabia was a leading member, as support for Saddam Hussein. As a result, up to a million Yemeni expatriates working in Saudi Arabia were sent home, plunging Yemen into economic disarray.

In 1995, Eritrea fought Yemen in a brief armed conflict over small but strategic al-Hanish al-Kabir, an island in the Hanish archipelago in the Red Sea. International mediation decided in Yemen’s favour. Since the attacks on the Twin Towers on 11 September 2001, Yemen’s government has sided with the United States in the battle against al-Qaeda.

Recently, Yemen has been strengthening its bonds with Arab states. There have been several agreements with Saudi Arabia regarding their non-demarcated border. Yemen is scheduled to become a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council in 2016. The country’s economic importance to other Gulf States is minimal, but its political significance is growing, thanks to its large population.

Yemen has always had friendly ties with the rest of the world. This has made foreign aid a significant factor in the Yemeni economy (8.2 percent of GDP in 1990, decreasing to 2.2 percent in 2006, and back to a significant level after the London donor conferences of 2006 and 2010). The Japanese, Chinese, and Russians have built roads across the country. European benefactors have contributed greatly to medical and social services and to the restoration of historic monuments.

The Military

Since 2015, Yemen has been embroiled in a three-sided civil war between the government of Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, backed by a Saudi-led coalition, the Houthi rebels, backed by Iran, and the southern secessionists, supported by the United Arab Emirates until July 2019. In late 2019, rapid shifts in the military balance saw the ejection of Hadi’s forces from his provisional capital in Aden, a major southern separatist offensive into government territory and a strong comeback by government forces. These shifts underlined not only the volatility of the conflict but also Yemeni forces’ reliance on foreign backers.

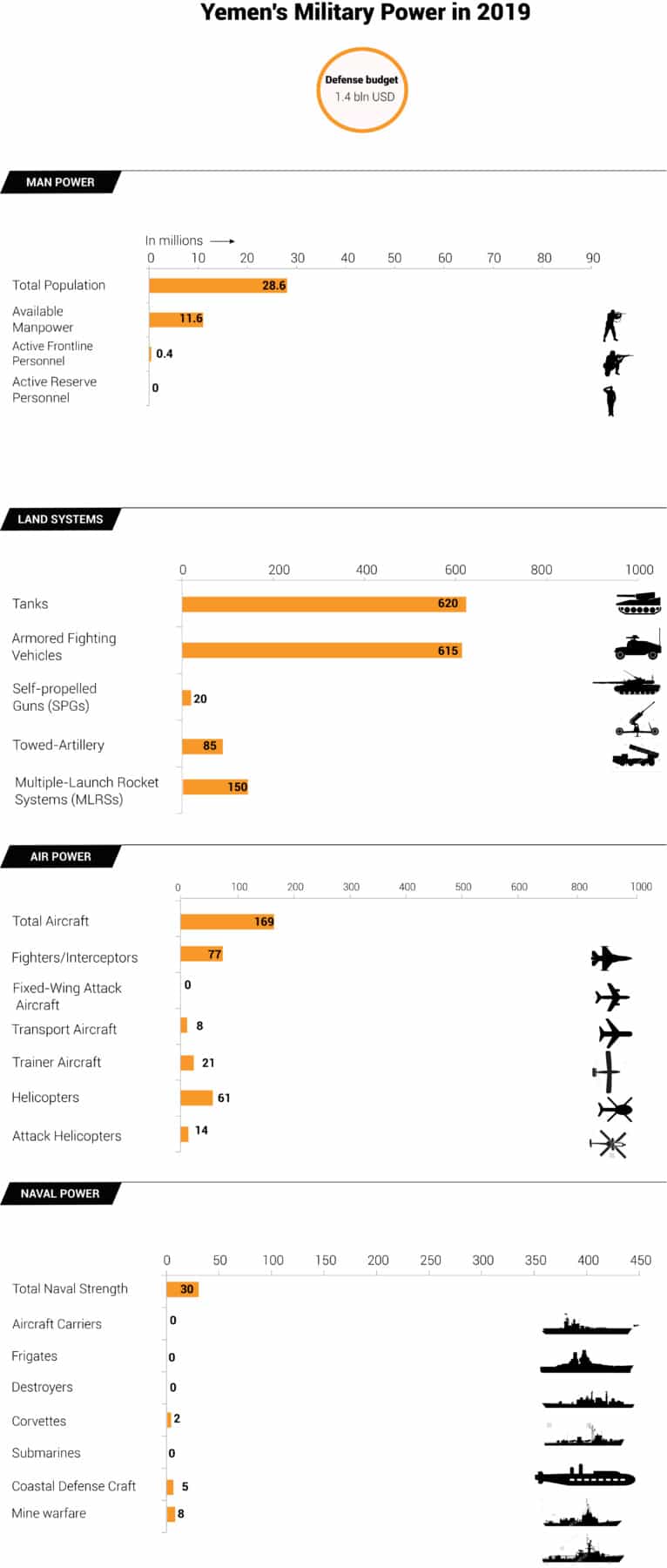

In 2019, Yemen ranked 73 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 575,253 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $1.4 billion. In 2014, military expenditure accounted for 0.4 per cent of GDP, compared with 4.1 per cent in 2013, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. More recent numbers are unavailable.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 30,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 30,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 169 | 56 |

| Fighter aircraft | 77 | 28 |

| Attack aircraft | 77 | 34 |

| Transport aircraft | 8 | 46 |

| Total helicopter strength | 61 | 53 |

| Flight trainers | 21 | 62 |

| Combat tanks | 826 | 27 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 615 | 72 |

| Rocket projectors | 267 | 13 |

| Total naval assets | 30 | - |

Yemen’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

Yemen’s Armed Forces are made up of the armed forces of the Soviet ally South Yemen, and those of Western ally North Yemen, following the unification in 1990.

The army remains an amalgamation of separate components. For an assessment of the combined armed forces, the American think tank CSIS writes: ‘Military Manpower: Total Yemeni military manpower was around 66,700 in 2006, with slightly larger paramilitary forces totalling 70,000.

These levels of total manning have been typical since the mid-1990s, although Yemen reached totals of 127,000 in the early 1990s. The Army had some 60,000 men, the Navy 1,700, the Air Force 5,000, and the Air Defence Force 2,000. There were some 50,000 men in paramilitary roles in the Ministry of the Interior, another 20,000 in tribal levies, and a small Coast Guard was being created.

Two-year conscripts made up a significant part of the total, although they were a small part of Yemen’s potential pool. The CIA estimates that some 237,000 young men became eligible for conscription in 2005. In broad terms, Yemen paid little attention to effective military manpower, lacked effective schools and career development programs, and did not have an effective NCO corps or mix of technical personnel.

As in all countries, there were some outstanding officers and NCOs, but Yemen did a poor overall job in developing suitable manpower quality.’ Yemen showed little interest in effective combined arms and joint warfare training and exercises.

The assessment by CSIS of the Yemeni armed forces is not flattering. According to the think tank, the Yemeni army has some effective battalion-sized elements, but is largely a hollow force, better suited for internal security purposes than warfare. It has a nominal strength of 60,000 men, many of whom are two-year conscripts. It has about 40,000 reserves, with little or no meaningful reserve training.

The Yemeni Air Force does not fare much better. It has a nominal strength of 3,000 to 3,500 men. It suffers badly from a lack of modernization and foreign support in recent years, although Yemen has acquired a few additional modern fighters over the past six years. In 2006, the Yemeni Air Force had 75 combat capable aircrafts (Jane’s estimated it at 84), 40 of which were in storage. It had 31 fighter interceptors, 40 fighter ground attack (FGA) aircraft, 18 transport airplanes, and 44 training craft.

The Yemeni Navy could, potentially, play an important role. In addition to its location near the Bab al-Mandab, Yemen has a 1,030 nautical mile coastline and major ports at Aden and al-Hudayda. There are important islands near major shipping channels, including Socotra, Kamaran, and Perim.

In 2006, the Yemeni Navy counted 1,700 men and was based at Aden, Ras al-Katib, and al-Hudayda, on the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, with smaller bases at al-Mukalla and at the islands of Perim and Socotra. The Yemeni Navy has undergone little modernization over the last decade. Between 2000 and 2005/2006, the fleet shrank in size, and manpower dropped slightly from 1,800 to 1,700.

In 2002, the mediocre Yemeni Armed Forces thrust themselves into the public spotlight when a North Korean freighter was intercepted by Western naval units in the Indian Ocean. The cargo documents stated that the vessel transported cement, but several Scud missiles were found hidden beneath a pile of sacks. Apparently, they were Aden-bound. Although not illegal, the find raised some eyebrows.

In 2011, the Yemeni army was split between the brigades and divisions supporting the regime of President Ali Abdullah Saleh and those supporting the protest movement. The split widened after Lieutenant General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, commander of the first armoured division and Saleh’s half-brother, announced he was backing the “peaceful youth revolution”.

Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, who was elected president in February 2012 after nearly a year of protests against Saleh, set about restructuring the army into four units: the land forces, navy, air force and border forces. He also abolished the Republican Guard, which was led by one of Saleh’s sons, and the First Armoured Division, which was headed by al-Ahmar. In April 2016, al-Ahmar was appointed vice-president.

In September 2014, Houthi rebels, who champion Yemen’s Zaidi Shia Muslim minority, seized control of the capital Sanaa. The following January, they surrounded the presidential palace, forcing Hadi to flee to the southern port city of Aden. Over the next three months, the Houthis and security forces loyal to Saleh attempted to expand their control, taking over many of the western regions. Alarmed by the rise of a group they believed to be backed militarily by regional Shia power Iran, Saudi Arabia and eight other mostly Sunni Arab states began an air campaign aimed at restoring Hadi’s government. After two years of fighting, no side appears close to a decisive victory.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Yemen’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: