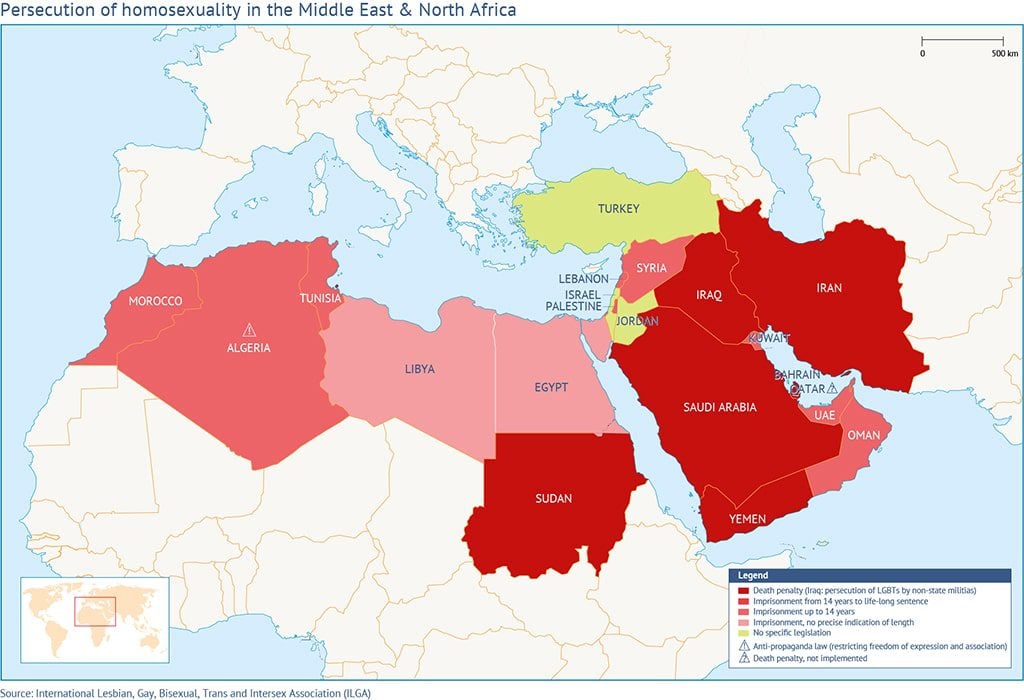

Are the Arab world and homosexuality incompatible? One might think so, given the news about anti-gay sentiment, raids on secret gatherings of gay people, and even death sentences.

But it has not always been this way. In the second half of the eighth century, for example, Abu Nuwas conquered the hearts and minds of his audience with poems that made fun of the newly emerging religion of Islam and spoke openly about drinking and pederasty. Nuwas faced no problems when he spoke of his lust for beardless young chaps; the caliphs of his day didn’t object. And, despite the obscene content of his poems as judged against present-day Islamic values, the name of Abu Nuwas is still familiar to most Arabic speakers.

Nowadays, the works of Abu Nuwas are, like homosexuality, forbidden in most Arab countries, but this general rule has an important nuance—the laws concern mostly male homosexuality. Lesbianism is less visible in Middle Eastern societies, and lesbians aren’t blamed for their sexual preferences to the same extent as gay men. The common belief in the Middle East is that only penetration counts as real sex. When two men have sex with each other, only the passive partner is generally seen as gay. The active partner is just seen as unleashing his heterosexuality on a man.

An example of Arab intolerance towards homosexuality is the case of the Queen Boat in Cairo. On 11 May 2001, 52 men were arrested aboard this ship, a floating gay nightclub. All were prosecuted for debauchery, obscene behaviour, or showing contempt for religion. The Cairo 52, as they became known, were beaten into confessions and were forced into forensic examinations to “prove” their alleged homosexuality.

In June 2015, a Moroccan man from Fez who was said to be gay was beaten by a mob. According to Human Rights Watch, the incident began when a taxi driver ejected the male passenger after a dispute, shouting repeatedly that he was a khanit, a local slang pejorative for a gay or effeminate man. A crowd surrounded the victim and started beating him, knocking him to the ground. This scene was captured on camera and posted on Moroccan news websites. “In the videos the victim appears to have long hair and to be wearing a white robe,” Human Rights Watch states.

Tolerance of Homosexuality

These frightening examples are just the tip of the iceberg, but there are also examples of gay emancipation in the Middle East. Take, for example, the emerging gay scene in Beirut. Homosexuality is still illegal in Lebanon, but the capital city seems to have become a meeting place for gay men from all over the Middle East, as well as for European gay men. Although gay clubs prefer to keep a low profile, adventure tours are being organized for gay travellers.

Even in Palestine, a relatively liberal Middle Eastern society, homosexuality can’t be displayed openly, but in Ramallah, the de facto Palestinian capital, a tiny gay scene has nonetheless emerged. In December 2015, a Palestinian Queer Film Festival was held, albeit outside of Palestine, in the Israeli city of Haifa. The goal of the festival, writes the American journalist Debra Kamin, was “to provide a platform for home-grown, gay-themed films at a time when most LGBT Palestinians still feel a need to stay closeted.”

There is some recent Arabic literature that features homosexual characters. One of the protagonists in the famous novel The Yacoubian Building (2002), by the Egyptian Alaa al-Aswany, is Hatim Rasheed, who is the editor of Le Caire, a French-language daily newspaper. Rasheed is presented as a rich and generous intellectual with a tumultuous gay love-life. Although it may be seen as a breakthrough that an Arab novel features a gay protagonist, critics point out that Rasheed’s homosexuality is explained by his miserable youth. Moreover, the author “punishes” his protagonist by having him die a violent death. The protagonist of Sirens of Baghdad (2007), by Yasmina Khadra, finds his uncle in bed with another man. As in al-Aswany’s novel, the gay character is killed.

Western Involvement

As soon as gay emancipation in the West became a main item on the human-rights agenda, many Western NGOs began to pay attention to the fate of homosexuals in the Arab world. Promoting gay rights “has emerged as a foreign policy objective for Western nations and a key programmatic priority for multilateral organisations such as the United Nations and the World Bank,” writes Omar G. Encarnación, professor of political studies at Bard College, New York.

This is something they shouldn’t do, argues the Palestinian-Jordanian scholar Joseph Massad. The promotion of gay rights in the Middle East, Massad wrote in his much-discussed paper “Re-Orienting Desire: The Gay International and the Arab World” (2002), is a “conspiracy led by Western Orientalists and colonialists which produces homosexuals, as well as gays and lesbians, where they do not exist,” by which Massad means that Westerners are trying to impose their norms of (acceptance of) homosexuality on another world, the Middle East, where things are not the same. By adopting the Western norms, says Massad, the inhabitants of the Middle East would place themselves outside of their societies, something they do not want.

Whether Arab gays need the help of Westerners or not, it is an illusion to think that gays in the Arab world exist only by virtue of the modern West. Of course, gays know how to find each other, in both Western and Arab countries, despite different social rules, laws, and traditions. Like their Western counterparts, Arab gays use web sites and dating apps to find each other and know which bars and clubs to go to. The fact that there is no open gay scene doesn’t mean that it can’t flourish underground.