On 15 October 2017, actress Alyssa Milano posted a tweet urging women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted to reply with ‘me too’ to give people a sense of the ‘magnitude of the problem’. The post followed allegations by scores of actresses against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. Very quickly, thousands of women shared the #metoo hashtag, including numerous women from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), who responded with the words ana kamen or “#أنا_كمان”, ‘me too’ in Arabic.

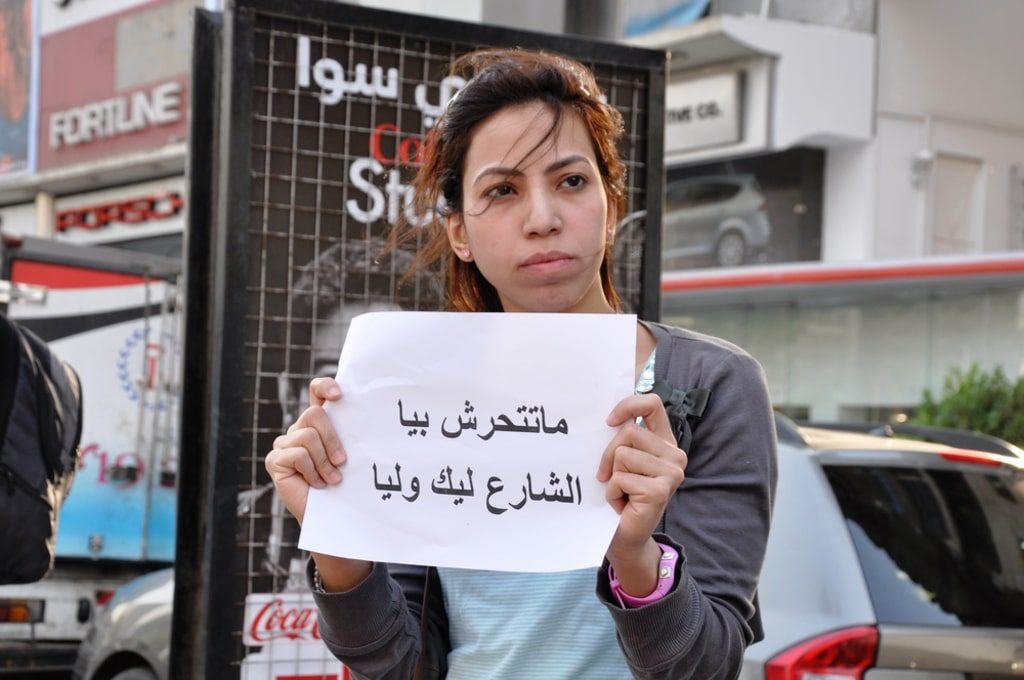

The most responses came from Egypt, which is unsurprising given that a 2017 poll by the Thomson Reuters Foundation rated Cairo as the most dangerous city for women. The poll was based on four criteria – sexual violence, access to health care, cultural practices and economic opportunities – and the results showed that ‘the Egyptian capital, with an estimated population in 2016 of 19 million, fared worst when it came to harmful cultural practices for women such as female genital mutilation and forced marriage, and was named the third worst city when respondents were asked if women were at risk of sexual harassment and violence’. Fanack Chronicle asked women from various MENA countries, including Egypt, about the impact of the #metoo campaign for them.

“I think it just made sense to Egyptian women, with statistics as high as 97 per cent or more of Egyptian women facing sexual harassment on a regular basis,” said a 30-year-old woman living in Cairo who asked to remain anonymous. “I feel it was a chance to make our voices heard, to give a perspective of how prevalent [sexual harassment] has become. I personally felt very emotional and sad thinking about all the times I have faced sexual harassment and how many other women also go through that experience regularly. I think a lot of the men, at least on my timeline, were shocked by the number of women they know who face such horrors.” She said she was first assaulted at the age of eight or nine, when her building’s security guard touched her breast while playing football with her, her brother and her cousin.

Nervana Mahmoud, an Egyptian writer and commentator on Middle East issues based in London, said that she had been harassed daily in Egypt and then Iran, despite wearing black and covering her hair. “The ordeal exposed the myth of modesty. Modesty doesn’t stop harassment,” she said. “A few weeks ago, a niqabi [veiled] woman in Egypt was harassed. When she posted her story on Facebook, she was mocked because her niqab was pink. The campaign is a step in the right direction, but there is still a long way to go.”

From Ramallah, 25-year-old Palestinian social media activist Mona Shtaya did not want to “stereotype Palestinian men since I always travel and this phenomenon is found in many countries. The difference being that compared to Egyptian men, here they don’t harass you physically most of the time.” She hopes the campaign will “lead to something more practical towards women. The phenomenon is huge and the sexual harassment doesn’t always have to be physical, it may be verbal or by looking at a girl in a bad way. Many people’s [social media] status confirm these things,” Shtaya said. “A few ladies shared their stories but most of them didn’t because they will face reactions from the community. We think this harassment may come from the clothes they wear or the way they act, so they may be labelled and stereotyped as not good girls.” When asked about the reaction of men, she was more cautious: “As usual on occasions like this or International Women’s Day or the International Day of the Girl, many men act like they are completely in solidarity with women, especially on social media platforms, but we’ll never forget that they are the same men who might harass us.”

Furthermore, women in the MENA region are often blamed for being sexually harassed or assaulted. In Egypt, for example, during the November 2012 protests in Tahrir Square, a wave of sexual assaults were reported. In response, several members of the Human Rights Committee of the Shura Council, Egypt’s Upper House, said that women were “100 per cent” responsible for being raped by placing themselves in “such circumstances”. Shame and fear of such social condemnation mean women are less likely to tell their families about what they have been through or reporting the incident to the police. Journalist and author Mona Eltahawy even described being assaulted by military officials. In these circumstances, declaring on social media what has happened to you can be risky and damaging to your reputation.

A Yemeni woman from Aden who lived in Saudi Arabia for 35 years said that the campaign “will not affect our society” but that she was hopeful for the future of Saudi women: “The evidence lies in the decisions made regarding women. King Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud is a source of pride for the women of Saudi Arabia. I don’t know if you’ve heard about the hashtag ‘the fall of Guardians’ but it talks about all Arab women’s rights. So I’m proud of the women who made the hashtag and wish all countries were like them. As for my country [Yemen], the development of women will take a long time. There, they complain about education, marriage of minors and taking inheritance rights. Many problems will also emerge after the war.”

By contrast, Kuwaiti academic and women’s rights activist Alanoud Alsharekh said that “maybe the effects won’t be immediate but … civil action can lead to policy change”. She is the chairperson of Abolish 153, a campaign to end honour killings in Kuwait and the region, and told Fanack Chronicle “that after the hashtag there have been more discussions of harassment on traditional media like radio stations”.

In Lebanon, where Article 522, which exempted the offender of rape and sexual assault, was repealed last August 2017, artist Noor Haydar was “not surprised [to learn] that many of my female friends have been harassed or assaulted”, and glad “that we can share it with each other”. However, she voiced the question that many women in the region have asked themselves: “How can we continue this conversation?”

In the MENA region and elsewhere in the world, the #metoo campaign has allowed women to share, express and illustrate the magnitude of the issue. Now, real actions should be taken to address it.