Introduction

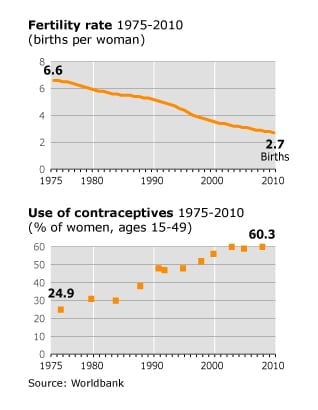

Egypt’s population is to a large extent homogenous: Arab and Muslim, with a substantial minority of Coptic Christians. On the other hand, the population is spread very unevenly across the country, with high concentrations living in the Nile basin, especially in the Nile delta. The majority of the Egyptian population, including many city dwellers, follow traditional relationship patterns.

Human Development

‘All aspects of human profile deprivation – except unemployment – have shown significant reduction over the last decade’, reported the UNDP Human Development Report 2005 on Egypt, and things have improved since then. More people have access to piped water, fewer children die before the age of five, life-expectancy has increased, more children participate in basic and secondary school, illiteracy continues to decline, and more people have access to health care.

Despite these gains, Egypt still lags internationally. Of 177 countries surveyed by the UNDP, Egypt ranked 104th in 2010. Of Egypt’s Arab and North African peers only Morocco, Syria, Sudan, and Yemen scored lower.

There are still enormous differences in human development between rich and poor, urban and rural regions, and men and women. Almost all Egyptian households are connected to the electricity network, but access to clean public water is not universal. Rural areas lag behind urban areas: 82.5 percent of the urban population is safely connected to a sewage system, but only 24.3 percent of the rural population. The UNDP Egypt Development Report 2005 identified the state of sanitation in Egypt as a ‘silent emergency’, posing a large risk to public health.

Infrastructure

Egypt’s cities are well connected by a network of roads, 78,641 kilometres of which are paved, but due to poor maintenance and heavy traffic, many roads are in poor condition. Road transport accounts for 85 percent of domestic freight and 60 percent of passenger movement. Intensive use has resulted in high levels of congestion. Cairo in particular suffers from constant traffic jams. Each year about 30,000 people are hurt, and 6,000 die in road accidents, one of the highest traffic-fatality rates in the world.

Railways

The national rail system is the oldest in the region, and time has taken its toll on the system. Accidents happen on local rail lines once or twice a year. More care is taken with trains used by tourists, and no accidents have been reported in recent years. Rail transport is available along the Nile and throughout the Nile Delta to the city of Alexandria. While rail accounts for a large share of the domestic passenger transport, its share of the domestic freight transport is low, at about 8 percent. Cairo has a modern metro system (partly underground, partly above ground), with two lines crossing and covering much of the city. Work has started on a third line that will lead to the International Airport; it was expected to open in 2010, but had not by the end of 2012.

Air travel

Air travel to all major destinations within Egypt is provided predominantly by the state-owned carrier Egypt Air. There are daily flights from Cairo to most international destinations.

Shipping

The Suez Canal is the crucial waterway between Europe (the Mediterranean Sea) and Asia (the Indian Ocean), making it one of the most important sea routes in the world. Thanks to this 163-kilometre-long man-made canal, all but the largest ships can avoid the expensive circumnavigation of Africa. Seaports handle up to 90 percent of Egypt’s international trade. The harbours are slow, inefficient, and hampered by corruption. The Nile and its canals make up most of the navigable inland waterways, totalling approximately 3,100 kilometres. Traffic by water accounts for only 4 percent of the transport of domestic freight.

Education

Since the 1960s, the Egyptian government has guaranteed free public education for all. The system envisions nine years of basic education up to the age of fifteen, followed by secondary education and higher education. Higher education includes public and private universities and al-Azhar University.

Although public education is free, indirect costs, such as private lessons, supplies, and transport, put a strain on poor families with many children. Extra private lessons, often taught by poorly paid schoolteachers after school, are common, despite an official ban on the practice. Students at the secondary level are in special need of additional tuition to compensate for the overcrowded classrooms, lack of discipline, and uninspired teaching by unmotivated teachers. This increases the costs of education for parents. It is estimated that 80 percent of secondary-school students receive private lessons. Teachers were among the first professional groups to hold wide protests after Mubarak’s fall, to demand a substantial increase in their salaries and improvement in working conditions.

The large growth in population puts an enormous strain on the underfunded education system. On average, every classroom in primary, preparatory, and secondary education counts more than forty children. universities and elementary schools are overcrowded, the result partly of the guarantee that every graduate of secondary school will find entry to one of the twelve state universities. Private universities, a highly lucrative business, are increasingly popular but affordable only for the upper-middle and higher classes.

Overall educational standards remain mediocre. Among the long list of problems are the rigid education system, the emphasis on rote learning as opposed to critical thinking and creativity, and poorly paid and unmotivated teachers.

Egypt has one of the highest illiteracy rates in the world (30.5 percent). Not surprisingly, the illiteracy rate is highest among poor and rural inhabitants. People from households headed by illiterates have a 57 percent probability of being illiterate themselves. The country has, however, made enormous progress in boosting literacy – from 26 percent of all individuals aged 15 years and older in 1960, to 69.5 percent in 2006. Performance is even better for those 15 to 24 years of age.

Health

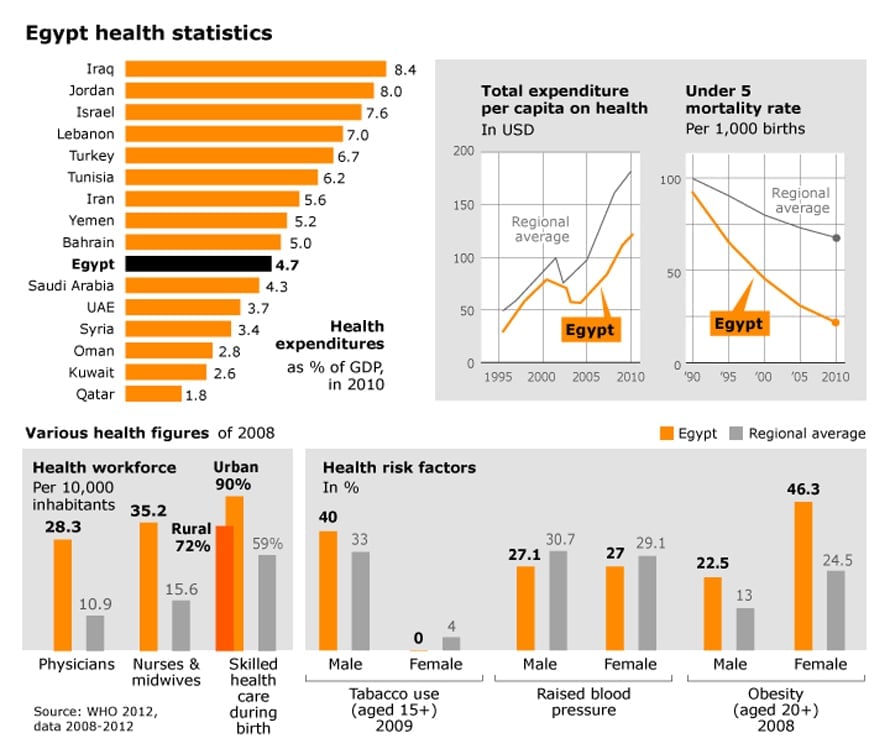

Free health care is a constitutional right of all Egyptians. In fact, all communities do have some sort of health service, mostly run by the Ministry of Health and free of charge or charging only a nominal fee. The government has steadily increased spending on public health care, but investment has not kept up with the huge increase in population, with the result that services are often poor.

Basic indicators of health are, however, improving. Immunization coverage has increased for all antigens to above 98 percent of the population in 2005, leading to a reduction of the mortality rate. Egypt has essentially eliminated polio, which was still prevalent in the 1990s. The infant mortality rate, the under-five-years mortality rate, and the maternal mortality rate continue to fall.

HIV/Aids has a low prevalence rate in Egypt, estimated at less than 0.1 percent of the population, but it has one of the highest rates of hepatitis C in the world. Between 10 and 15 percent of population carry antibodies for hepatitis C, and some 7 to 8 percent of the population suffers from chronic hepatitis C, predisposing them to serious liver disease. It is also estimated that 10 to 15 percent of the population suffers from diabetes, the vast majority due to obesity and an unhealthy lifestyle.

Unemployment

The labour market is estimated at 22.34 million people (2006), of whom 78 percent are men. The government remains the major provider of non-agricultural employment (some 24 percent of the workforce), and the informal sector is the main source of low-productivity and low-income employment, especially for women.

Economic growth in the past few years has failed to create enough jobs to match the growth in the labour force, which averages 2.5 percent per year. More than 60 percent of the unemployed are youth.

The official unemployment rate has remained the same, around 10 percent over the past few years, but has worsened in absolute numbers. The total unemployment figure was put at 1.5 million in 1997 and increased 58 percent to 2.3 million in 2006.

In 2012, unemployment is probably higher than the official government statistics show, possibly 15 to 25 percent higher. Unemployment among university graduates is thought to be even higher, around 40 percent for men and 50 percent for women.

The past decade has seen a shift of employment from the public sector to the private sector, but employment growth in the private sector is mostly in uncertain jobs without social security.

Urbanization

The north of Egypt, where the major cities are located and most economic activity takes place, is generally more prosperous than the south. This leads to substantial migration from the rural south to urban areas in the north, particularly Cairo. Overall, 42.6 percent of the population lives in urban areas, the same proportion as ten years ago. Out of the total population, 11 percent (7.8 million) live in Cairo, 9 percent (6.3 million) in its sister-city Giza, and 6 percent (4.1 million) in Alexandria.

In attempting to relieve the pressure on urban areas, the government has encouraged migration to reclaimed lands in the desert. This strategy has not proven very successful, because the newly irrigated agricultural lands need a great deal of financial investment from farmers and tend to be unattractive because of their remote location.

In general, more people still move from rural land to urban areas than the other way round. Despite high unemployment and lack of housing in the cities, young people still believe the urban environment provides more opportunities. Recent governments have made progress in providing rural areas with more electricity, drinking water, and roads, but the main obstacle facing the development of rural areas remains the lack of job opportunities, pushing many (mainly young men) in those areas to migrate to larger cities.

A recent phenomenon is that of the so-called satellite cities. Although several were developed under the rule of Anwar Sadat, in order to find solutions to the overpopulation of the country’s capital, they increased prodigiously during the last years of Mubarak’s regime. Unused desert land was sold to wealthy businessmen who developed the new satellite cities. These differ greatly from those built during the Sadat era, in that they are developed exclusively for middle- and upper-middle-class families. These families have gradually left the city seeking clean air and luxury in gated, controlled environments that offer more resources than the inhabitants need or can sustain. As more than 1 million had already moved by the last year of Mubarak’s rule, Cairo became more and more the city of the marginalized poor, and slums and crime increased. It is speculated that this segregation of the poor contributed to the pervasive sense of discontent leading up to the revolution of 25 January. Businesses and investments have also moved outside the city, creating a void in the capital. Moreover, as these settlements are located on desert land but offer such luxuries as parks, gardens, and pools, they are steadily creating shortages of water and power.

Poverty

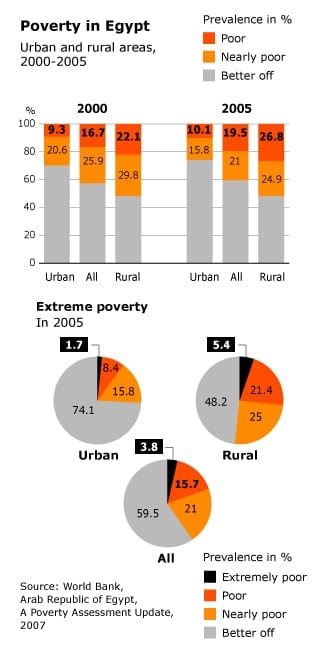

Egypt is not trapped in poverty, according to the UNDP Egypt Human Development Report 2005. Rather, it is recognized as a middle-income country, although poverty is a serious, widespread problem. The World Bank calculates that about 40 percent of the population is poor. This represents 28 million people, of whom 2.6 million (3.8 percent of population) are categorized by the UNDP as ‘extremely poor’.

34 percent of Egyptians have less than one USD a day to spend, and 42.8 percent live on two USD a day or less.

Without the existing food subsidies, an additional 7 percent of the population would be poor, and among those, 4.3 percent of the population would become very poor. The majority of the poor live in households where the head of the family is illiterate or barely literate. In general, large rural households with young children (under five) and low education levels run the greatest risk of poverty.

The World Bank uses the category ‘extreme poverty’ for those unable to provide even for basic food, ‘absolute poverty’ for those spending less than needed to cover minimal food and non-food needs, and ‘near poverty’ for those spending barely enough to meet basic food demands and slightly more than essential non-food needs. The three categories together are defined as ‘all poor’.

Regional Disparity

Improvements in the national human-development indicators, as defined by the UNDP in 2005 and 2008, are not so much the result of higher standards achieved overall, but of the catching-up of previously under-privileged parts of society.

Rural areas still lag significantly behind urban areas. Upper Egypt (the south) does not perform as well as Lower Egypt (the Delta and other northern regions). Although the differences have become smaller in the past decade, the gap is still large in areas such as education, health care, access to sanitation, unemployment, and poverty. For example, the proportion of people spending less than two USD a day is 50 percent in rural Upper Egypt compared to 5 percent in the cities.

The situation in Upper Egypt is particularly alarming because poverty is increasing among individuals who have had a basic education, compared to those who have learned only how to read and write. The explanation for this lies in the faster population growth and slower job creation in the south.

The total population in urban areas increased by 40 percent in the ten years leading up to 2006, when it numbered 31 million. In rural areas the total population increased significantly faster, by 64 percent from 1996 to 2006, and is currently put at 42 million.

The five lowest-ranking governorates, according to the UNDP Human Development Index, are all in Upper Egypt, while the five highest-ranking governorates are all in Lower Egypt.

Women

The so-called gender gap is slowly narrowing in Egypt. There have been substantial improvements in female literacy rates, school-enrolment rates, labour-force participation, and employment.

Particularly in education women are making great strides. Of the total number of women older than fifteen, only 22.7 percent have had a secondary education, but among those of school-going age the enrolment rate is 70 percent. Women now sometimes surpass their male counterparts in absolute numbers. While women made up only 31 percent of university graduates in 1996, their proportion increased to 52 percent in 2006. From primary education to university, roughly half the students are now females.

Despite these gains, Egypt’s ranking on gender empowerment is, according to the UNDP, still among the lowest. Women in Egypt score poorly in economic participation, economic opportunity, political empowerment, health, and well-being. The scores on most of these criteria have been improving over the years, but they still lag behind the scores for males. For instance, women represent only 22 percent of the total labour force, and the unemployment rate for women is four times higher than unemployment rates for men (24 percent vs 6.8 percent).

Under Mubarak, efforts were made to increase the number of women in high positions. Before the December 2010 elections for the People’s Assembly, the government amended the law and granted women the highest quota ever of parliamentary seats, but the 64 seats allocated to women were occupied by supporters of the now-dissolved former ruling NDP.

After the fall of Mubarak the quota system for women was cancelled in the new election law introduced by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF).

The new election law is based on the party-list system, which obliges each party to include at least one woman among the top five name in its list of candidates. Due to the growing influence of fundamentalist Islamic groups, women have however almost always failed to win parliamentary seats in elections. Any future President will thus probably select women for the ten seats he is entitled to appoint ten members in Parliament. Traditionally, those seats go to women and Coptic Christians. In 2007, the first female judge was appointed to the Supreme Constitutional Court.

In human rights, Egypt scores low on gender equality. Freedom House gives Egypt only 2.3 out of a maximum seven points for ‘gender equality’. Often, men and women enjoy different rights under Islamic jurisprudence. A woman inherits half of what a man does, and divorce can be difficult if the husband refuses. As a solution, Egypt adopted the so-called Khula Law in 2000, which gives a woman the right to divorce her husband over his refusal. This law has come under attack since the Islamist takeover.

According to the Carter Center, women were underrepresented in the 2011 parliamentary elections. The number of women eventually elected is considered a serious concern: out of the total of 628 seats, only 14 were taken by women. The new cabinet of President Morsi continues the tradition established by Mubarak of including only two women. Under Morsi, these are the Minister of Insurance and Social Affairs and the Minister of Scientific Research. Out of the seventeen presidential consultants, two are women.

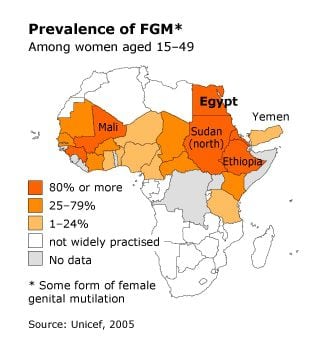

Female genital mutilation

Domestic violence against women is widespread, and Egypt has a high rate of female genital mutilation (FGM). Although the government has banned the practice since 1996 (except for health reasons), UNICEF statistics show that 97 percent of Egyptian women between the ages of 15 to 49 have been subjected to some form of FGM; 47 percent of mothers have at least one mutilated daughter.

FGM is an ancient custom of African origin and is practiced by both Muslims and Christians in Egypt, despite its explicit rejection by the Coptic papacy and al-Azhar (although there are some Islamic scholars who do not share this opinion).

Households

Almost half of Egyptian households consist of five or more persons. Generally, sons and daughters live with their parents until they marry. In rural areas, brides are taken into the household of their husbands’ parents.

A World Bank study reveals that there is a strong correlation between household size and poverty. The poor tend to support a higher number of dependents. Having a large number of children still too young to contribute financially to the family has a strong impact on poverty. Almost one-third of all households consisting of six or more persons are in poverty, accounting for 74 percent of all poor individuals in Egypt.

Civil Society

Despite the discouraging authoritarian restrictions enacted by the regime, there are about 21,000 active civil-society organizations in Egypt. Of these, 15,154 were registered in 2010 as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including service-delivery and welfare organizations, development organizations, and advocacy organizations (advocating for human rights, consumer protection, gender issues, and environmental protection). NGOs need a licence from the Ministry of Social Affairs, but it is the Ministry of Interior that is actually given the power to grant permissions, on the pretext of maintaining internal security. Many organizations focusing on human rights are therefore rejected. The NGOs that are officially recognized are allowed to receive funding from abroad. Several NGOs were allowed to operate in the country without the proper licensing, which, for example, gave the SCAF the opportunity to intervene in 2011, after the revolution. Led by Minister of International Cooperation Fayza Abou al-Naga, numerous NGOs were raided, their computers and files confiscated, and 43 employees, among them 19 American citizens, arrested. They were accused of illegal operations and receiving foreign funding that was portrayed in the media as a means of exerting foreign influence on Egyptian national affairs.

The Constitution grants the right to create trade unions or professional associations, known as syndicates, for professions such as lawyers, judges, doctors, teachers, engineers, and journalists. In reality, however, the Mubarak government limited their independence, especially when it became clear in the 1990s that many of the boards were dominated by Islamists. Most unions and syndicates were prohibited from holding board elections. All trade unions fell under the authority of the Egyptian Trade Union Federation, which is controlled by the government.

The 2008 Egypt Human Development Report of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) focused specifically on the role of civil-society organizations in Egypt and stressed their importance as a ‘third pillar alongside the state and the private sector’ for sustainable development. It referred to the often hostile attitude of the state towards civil society: ‘The continued existence of Egypt’s Emergency Law, and the application of the penal code to infringements of the Association Law are significant legislative barriers to effective civil society activity.’

During the protests against Mubarak, a meeting was held on 30 January 2011 in Tahrir Square between representatives of various trade unions. The meeting resulted in the formation of the first independent trade union, the Egyptian Federation for Independent Trade Unions. The federation called for a general strike and published a list of demands for wage reform, welfare reform, workers’ rights, and the release of opposition detainees. Immediately after the revolution, the Real Estate Tax Workers Union, an independent trade union, was established. The Revolutionary Socialists Movement is active in developing the trade unions of Egypt. Since the lifting of the Emergency Law, progress in this field appears possible.

Crime

Under Mubarak, Egypt had one of the lowest crime rates in the world. The President maintained one of the largest-ever internal security forces in the region, reaching nearly one million personnel in a more than a dozen security departments and branches. Anti-riot police alone, known as the State Security Forces (after the revolution renamed ‘Central Security’), had more than 250,000 soldiers throughout Egypt. The apparent omnipresence of security personnel throughout the country had a dampening effect on crime, as well as suppressing political opposition. The police had a reputation of practicing systematic torture and other abuse of detainees and prisoners. Thus, police and other security establishments were among the first to be targeted by the millions of Egyptians who revolted against Mubarak. After less than four days of heated clashes with protesters, the security forces collapsed and were withdrawn.

The new military rulers sought to rebuild the Interior Ministry, but the lack of security remains the largest problem since the Mubarak’s fall. Human-rights activists charge that police officers were on an undeclared strike because they were angry that nearly three hundred of their colleagues were put on trial for killing protesters during the 2011 protests. They have also complained that the police have lost the respect – and especially the fear – of Egyptians that they enjoyed for decades. The former Interior Minister, Habib al-Adli, was charged with building an undeclared alliance with government-paid thugs (baltagiya), whom he used during parliamentary elections to attack government opponents so that the state would not be seen to be involved directly in the violence. Those thugs, mainly poor, young, unemployed petty criminals, are now charged with carrying out most of the crimes committed in Egypt, due to the lack of security personnel.

Much organized crime, violent crime, and theft in Egypt is drug-related. The most popular drugs in Egypt are hashish, bango (marijuana), legal pharmaceutical products, opium, and heroin. Some incidents of violence, directed mainly against women, arise from family ‘honour’ codes.

Egypt has been known as safe for foreigners. Kidnappings of foreign nationals for political or commercial objectives have been uncommon, and the government has been committed to safeguarding visitors and foreign property. The greatest threat to tourists has been attacks by extremist militants, who targeted the tourist sector deliberately to damage the economy and undermine the regime, as was the case with the bombings of resorts in the Sinai Peninsula between 2003 and 2005.

Tourism and visits by foreigners have, however, dropped sharply since the revolution of 25 January. During the demonstrations, foreigners – specifically journalists and foreigners taking part in the demonstrations – became targets of the security forces. Some foreigners were harassed, arrested, and/or deported. Throughout the year following the fall of Mubarak, foreign reporters and photographers were harassed by security and army forces while covering demonstrations, sit-ins, or protest marches. Moreover, the police, security forces, and army made efforts to portray the revolution as influenced by foreign interests, thereby effectively creating an atmosphere of xenophobia. This reached its peak with a TV commercial portraying a foreigner speaking Arabic fluently who was revealed to be a spy. The audience was advised to beware of ‘such foreigners’. The commercial was heavily criticized inside and outside Egypt and was removed from television shortly after it aired.

The withdrawal of police and security forces from the street after Mubarak stepped down created an unstable security situation in the country. The lack of control, even in traffic, and the sudden spread of firearms posed great challenges for the army, which was forced to take on the responsibility of enforcing security on a daily basis. The resulting increase in crime not only added to people’s weariness with the revolution and its benefits but also enabled the police and security forces to return, soon after the recent presidential elections, more or less as they had left, with the same brutality and force.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Egypt’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: