For decades, the residents of North Sinai have suffered marginalization and the absence of a state presence, resulting in difficult living conditions, widespread unemployment, poverty, disease and an extremist ideology that has found fertile ground. However, after the January 2011 revolution, the suffering and abuse intensified. The population faced unprecedented violence, a policy of systematic displacement and forced evacuation that has left many towns and villages deserted and, in many cases, destroyed.

Sinai’s residents have long suffered because of the strategic location of the peninsula in eastern Egypt and its role in historical conflicts, especially with Israel. Following the conclusion of a peace treaty with Israel in 1979 and the return of Sinai to Egyptian sovereignty in 1982, the population has waited – in vain – for the promises of development and reconstruction to be fulfilled. Under former President Hosni Mubarak, North Sinai was largely ignored by the state. Health and education services deteriorated and there were no universities, cultural centres or cinemas in the entire governorate. With the scarcity of job opportunities – except for some agricultural work – and the Israeli and Egyptian blockade of the Gaza Strip, which borders the governorate, smuggling became a source of income for thousands of people. In parallel, extremist ideology began to take hold.

Sinai and terrorism

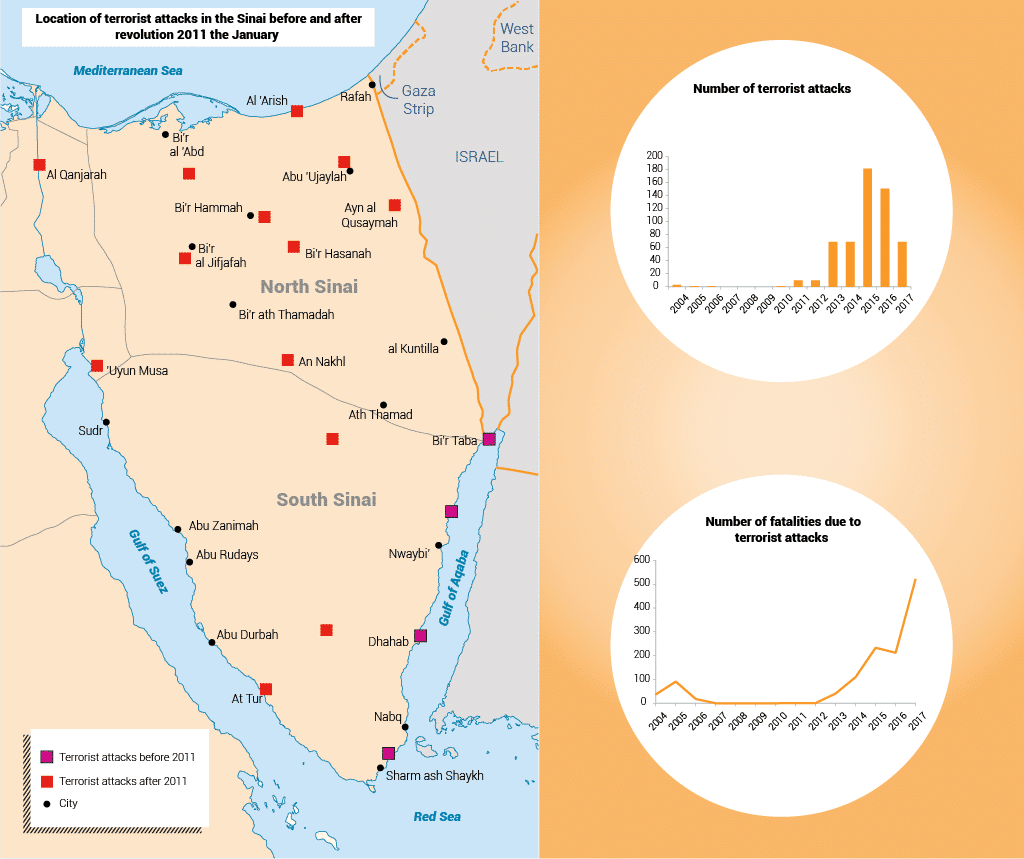

Sinai was the target of several terrorist attacks before the January 2011 revolution, specifically in 2004, 2005 and 2006, which claimed the lives of dozens of tourists and security personnel. Although all these attacks happened in South Sinai, they were usually followed by persecution of the residents in both the north and south. After the fall of Mubarak in 2011, North Sinai experienced more violence and armed attacks, starting with the bombing of the gas pipeline between Egypt and Israel, which was targeted around 15 times.

The army and police force were subsequently also targeted, especially following the emergence of multiple armed groups with links to al-Qaeda, namely Jund al-Islam. Other groups with links to the Islamic State were also active, such as Wilayah Sinai. Among the most prominent attacks was the first Rafah massacre in August 2012 on the Egyptian side of the Rafah border crossing with Gaza. The incident resulted in the death of 16 officers and recruits and the wounding of seven others. Eight attackers also seized two military armoured vehicles and tried to storm the border. They were stopped by Israeli forces, and all eight were killed.

This incident was followed by several others, which increased in frequency after the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi in a military coup in July 2013. There were more than 1,000 operations, most prominent of which was the Karam al-Qawadis operation, in which armed groups attacked several security forces simultaneously in October 2014; the bombing of the Russian Metrojet flight 9268 by the Islamic State, which killed all 224 passengers and crew; and the massacre in the al-Rawdah mosque, which left about 305 worshippers dead, or around a third of the men in the village. The most recent attack was against security forces during the Eid holiday prayers on 5 June 2019, in which two officers and eight soldiers were killed. In total, nearly 1,000 soldiers, army and police officers have died, and thousands of civilians have been victims of terrorism and counterterrorism operations.

Military operations

The first counterterrorism operation carried out by the army was Operation Eagle, which was launched in August 2011, followed by Operation Sinai in August 2012, Operation Right of Martyr in 2016 and the Comprehensive Operation in 2018. The operations included ongoing confrontations between the two sides, with local residents often being caught in the middle. Armed groups also specifically targeted civilians in many operations, especially those believed to be collaborating with the army. These collaborators were usually executed in public as a means of intimidation.

For its part, the army intensified its killing sprees, made arbitrary arrests and tortured residents to obtain information or as punishment for suspected collaboration with terror groups. According to Human Rights Watch, Egyptian security forces arrested about 12,000 people between 2013 and 2015, most of whom were tortured or forcibly disappeared. In 2016 alone, the Nadeem Centre for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture documented more than 1,200 extrajudicial executions, before it was closed by the authorities.

Displacement

Under the barrage of artillery fire, aerial bombardment and bullets, residents faced a systematic plan to displace them from their towns and villages. This started with the government’s decision to evacuate a 400-metre-wide area along the border with Gaza – a total area of approximately 80 square kilometres. The evacuation expanded to include the city of Rafah and almost all the surrounding villages along with the imposition of a blockade to prevent delivery of food items and other goods, while allowing the passage of cars to transport those who wanted to leave. Residents told Fanack that security forces seized and burned several cars trying to bring food to the villages, forcing some residents to eat fruit and leaves. Of the 11 villages in central Rafah, only a few residents still remain in al-Husaynat, according to people living in the adjacent area of Sheikh Zuweid.

However, the evacuation of Sheikh Zuweid and al-Arish soon followed. According to testimonies from residents of Sheikh Zuweid, all the inhabitants were displaced from the villages of Toumah, Lafitat, Zawaria, al-Muqataah, al-Ghara and al-Kharoubah, while the population in the remaining villages decreased dramatically. President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi subsequently issued a command to set up a 5 km perimeter around al-Arish airport, necessitating the evacuation of 25 km of the city’s 48 km area and the abandonment of hundreds of hectares of farmland that were the main livelihood of thousands of people. The consequences can be seen in aerial photographs published by Human Rights Watch in 2018.

According to recent testimonies, living conditions in Sheikh Zuweid have improved in 2019 compared to last year, which residents described as extremely harsh. Some food items and goods are getting through, although fuel sales have been cut to an average of 30 litres per week for private cars and 60 litres for transport vehicles. The only petrol station in the governorate is operational again, although artillery and aerial bombardments and house demolitions continue. In May, five people were killed and eight injured when two missiles were fired at the village of al-Jura, 10 km south of Sheikh Zuweid.

Lengthy and humiliating security checks also continue at checkpoints and during random inspections. Periodic arrests are carried out of men and women suspected of terror activities or of having family connections – even distant ones – with wanted persons. The lucky ones are detained while others are never seen again and declared killed in armed clashes in official statements.

Besides the poor security situation, the confiscation and destruction of agricultural land and the imposition of the military cordon has pushed many residents into poverty. Power outages are frequent and can sometimes last for days. Moreover, no drinking water has been pumped into Sheikh Zuweid since February 2018, and the population relies on groundwater. Most of the schools, hospitals and health-care facilities in villages are out of service although they are mostly functional in the cities. This is coupled with severe restrictions on journalists, a permanent curfew and denial of entry to the governorate, effectively isolating it from the rest of Egypt.

Deal of the century

Amid these conditions, rumours have circulated that the evacuated areas are part of America’s so-called ‘deal of the century’, which proposes an economic solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The Israeli newspapers Israel Today and Yediot Ahronoth reported that the deal hinges on the establishment of industrial and commercial projects for the Palestinians in East Sinai as well as the construction of an airport for their use, with Egypt facilitating the entry and exit of Palestinians in exchange for huge financial incentives.

These rumours, coupled with Egyptian silence on the matter, have led to widespread speculation and concern in the governorate. One of the residents Fanack spoke to said, “[The extreme living conditions in Sinai] are not real suffering; our real suffering are the unknowns that the state has put us through and the lack of a future. We are prey to rumours that disrupt any plans of stability or resilience.”