Introduction

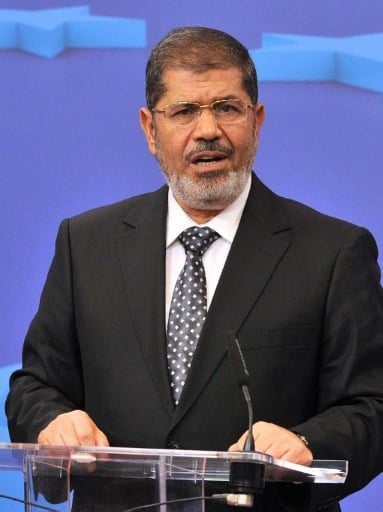

It was under the aforementioned circumstances that Muhammad Morsi Isa al-Ayyat, the presidential candidate of the Freedom and Justice Party of the Muslim Brotherhood, assumed power on 30 June 2012. He won 51.7 percent of the vote against Ahmed Shafik, the last Prime Minister appointed by Hosni Mubarak, who was widely considered to be an extension of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party (NDP) rule. Morsi was the first civilian president of Egypt.

Morsi's domestic policy

Since his election, Morsi focused on consolidating his rule domestically. First, he reinstated the Islamist-majority Parliament that was dissolved by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) earlier and appointed the Islamist sympathizer Hesham Qandil as his new Prime Minister. He proceeded to cancel the restrictions imposed on his office by the SCAF and asked Minister of Defence Field Marshall Muhammad Hussein Tantawi and Army Chief-of-Staff Sami Anan to resign.

He replaced Tantawi with the devoutly religious Abdul Fattah al-Sisi. The head of the intelligence and the commander of the Presidential Guard were also fired and replaced. Most key posts in government were held by Muslim Brotherhood members or by bureaucrats who sympathized with the Islamists. After the appointment of Muslim Brotherhood member Salah Abdel-Maqsoud as Minister of Information, the editors-in-chief of the country’s main papers were also reshuffled.

In the opinion of some, the steps Morsi took on the domestic front should be perceived as measures necessary to purge the old elements of the NDP and the influence of the military on politics, economy, and society and replace them with civilian elements, even if they are Islamist. To others, they amounted to an Islamization of the state, particularly as Morsi also pardoned and freed all Islamist prisoners upon assuming office.

What is clear, is that Egypt became polarized between Morsi’s Islamist supporters and his opponents, including leftists, liberals and secularists. During his election campaign, Morsi had promised to build a ‘democratic, civil and modern state’ that would guarantee the right to freedom of religion and peaceful protest. Morsi had presented himself as a bulwark against Mubarak’s old guard. Yet his rule was characterized by monopolistic governance, overlooking the need to share power.

Morsi and his Freedom and Justice Party overstated their narrow gains (including the referendum on the Constitution) as mandates to shape policy. During the process of writing the Constitution, Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood was accused by the opposition of failing to compromise on key issues, and minority representatives walked out on the Constituent Assembly. Morsi’s November 2012 constitutional declaration, in which he declared himself free from judicial oversight, sparked wide protests throughout the country.

Although Morsi, in December 2012, annulled the constitutional declaration, an atmosphere of distrust towards the Muslim Brotherhood persisted. Morsi saw little need to come to a compromise with the non-Islamist opposition, alienating not only the liberal and Christian opposition, but also the Salafi al-Nour party, which earlier had supported the Muslim Brotherhood but now criticized Morsi’s performance.

With limited checks and balances (Parliament had been dissolved in June 2012) Morsi moved to monopolize institutions (i.e. he installed Islamist supporters) and sideline the judiciary, which the Muslim Brotherhood perceived as a remnant of the Mubarak regime (felul). Morsi in November 2012 handpicked a new Prosecutor General (Talaat Ibrahim Abdallah), a step which sparked protests from prosecutors who feared for the judiciary’s independence (Abdallah resigned in December 2012 under pressure from protestors).

With the second anniversary of Egypt’s revolution, January 2013, Egyptians took to the streets in protest against Morsi’s rule, revealing their deep dissatisfaction with the so called ‘Ikhwanisation’ of society, the increasing violence and repression, the deterioration of living standards and ongoing corruption. Fears that Egypt’s newfound freedoms would be stifled by the Muslim Brotherhood’s authoritarian methods and Islamist agenda, were also a major reason to protest. In addition, Morsi had been unable to reform or hold accountable the security forces – whose abusive ways had been one the grievances of those Egyptians who protested against Mubarak.

The deadlock between the President and the opposition continued throughout the Spring of 2013. Violence reached its peak during assaults on the Muslim Brotherhood headquarters and the Presidential Palace in Cairo in March 2013. Unrest was not limited to the political opposition. Police and security forces organized nationwide strikes, an unprecedented move.

Violent clashes between protesters and security forces in Cairo, Port Said, Suez and Ismailiya led to dozens of casualties. In January 2013, Morsi announced a month-long state of emergency and called for a dialogue; the oppositional National Salvation Front (NSF), a coalition of deeply divided parties, rejected his call and instead demanded a national unity government and amendments to the Constitution.

Prime Minister Hisham Qandil subsequently increased the Muslim Brotherhood’s representation in the cabinet from eight to ten ministers, replacing two ministers involved in crucial talks with the IMF. Finally, Morsi, in June 2013, appointed seventeen new governors, several of whom from his own Muslim Brotherhood. Adel Khayat, who was appointed as governor of Luxor, was a member of the former armed group al-Jama’a al-Islamiya, which was implicated in a 1997 attack on tourists in Luxor.

In response to the political establishment’s failure to resolve the crisis after Morsi’s November 2012 declaration, youth activists launched a campaign called Tamarod; demands included the establishment of an interim government, amendments of the Constitution and early presidential elections. Tamarrod claimed it gathered 22 million signatures, at first glance drawing wide support from activists, political parties and ordinary citizens.

Tamarod called for a mass demonstration on the first anniversary of Morsi’s presidency on 30 June 2013. Tens of thousands of Egyptians took to the streets to call for the resignation of Morsi. Likewise, pro-Morsi demonstrations were held throughout the country. Clashes with security forces on 30 June 2013 left at least 24 dead and hundreds injured, most of whom anti-Morsi protesters, according to Human Rights Watch.

Military coup

Egypt’s Defence Minister Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, on 1 July 2013, announced a 48-hour ultimatum and warned that it would take steps if Morsi’s government would not accede to the protesters’ demands. However, Morsi ignored the warning, downplayed the mass June 30 demonstrations and offered insufficient concessions (including a national unity government and review of the Constitution).

On 3 July 2013, al-Sisi intervened and announced that President Morsi would be relieved from his duties and the Constitution suspended. An interim government led by the president of the Supreme Constitutional Court Adli Mansour would be formed, which would pave the way for new elections.

The military’s ‘new roadmap’ was supported by the NSF, al-Nour, Sheikh al-Azhar Ahmad al-Tayyeb and the Coptic pope Tawadros II. Interim President Adli Mansour on 8 July issued a constitutional declaration, announcing a nine-month transition plan. The committee which was to propose amendments to the Constitution (Articles 28-29), ‘representing all categories of society’, would not however include either Muslim Brotherhood or al-Nour members (they are not mentioned in Article 29).

From the viewpoint of the Muslim Brotherhood, which regarded the new government as illegitimate, the military was bent on restoring the old order.

Indeed, the military established facts on the ground by installing a new government, a constitutional revision committee and by organizing a referendum followed by parliamentary and presidential elections. It did so without any parliamentary oversight. However, the installation of a new, civilian-led government marked a departure from the military’s earlier approach, when it took to ruling Egypt itself.

The military coup led to more violence and polarization. Pro-Morsi protesters, demanding the reinstatement of Morsi as President, held peaceful sit-ins and demonstrations at Rabaa al-Adawiya square and al-Nahda in Cairo, where they clashed with security forces and anti-Morsi protesters. On 8 July, 51 people were killed when protesters gathered outside the Officer’s club, followed by another massacre on 27 July when 74 people were killed, many shot in the head and chest.

After the Egyptian cabinet had authorized authorities to ‘take all necessary measures to put an end to the demonstrations’, Armed Forces on 14 August 2013 moved into both main protest sites and used ‘systematic and unjustified excessive force and live gunfire’, according to a report by EuroMid Observer. Euromid Observer estimates that at least 914 protesters were killed on the first day and that thousands were injured.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has called it ‘the worst mass unlawful killings in Egypt’s modern history’. HRW also reports that some gunfire was used by protesters against the security forces. However, according to HRW, the use of lethal force was not justified by the disruptions caused by the demonstrations or the limited possession of arms by some protesters.

In the wake of the coup and the ensuing violence, the official line toward the Muslim Brotherhood became even grimmer. Scores of Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist leaders were arrested. Former President Morsi was detained by the military and moved to a secret location. The state prosecutor on 1 September 2013 referred Morsi to trial on charges of incitement to murder and violence, referring to clashes outside the Presidential Palace in December 2012.

Non-Islamist media have denounced the Muslim Brotherhood as an extremist, and sometimes, terrorist organization, backed by foreign interests, including Hamas and Syrian refugees in Egypt. A defamation campaign emerged in the Egyptian media, targeting those who were said to support the Islamists, including Palestinians and Syrians.

Palestinians were accused in the media of meddling in Egyptian affairs and even of being responsible for attacks on security forces in the Sinai. Nine Egyptian human rights organizations issued a statement condemning the ‘false information some Egyptian journalists are resorting to, to instigate hatred against the Palestinian people’. One of the first acts the military regime took was to ban Palestinians from entering Egypt from Gaza.

For their part, Muslim Brotherhood supporters at the sit-ins in Cairo had accused Copts of playing a role in ousting Morsi or helping to launch a crackdown on pro-Morsi protesters. Immediately after the crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood protesters on 14 August, crowds of men attacked Coptic churches, schools, businesses and homes in several governorates. According to Human Rights Watch, at least 42 churches have been attacked, 37 of which were torched or damaged. Violence against Copts had already emerged directly after the military coup. While the Muslim Brotherhood was accused of the attacks, authorities at the same time were accused of playing a role in inciting the violence and using it as an excuse to impose the emergency law (under the pretext of fighting terrorism). According to Human Rights Watch, in most cases neither the police nor the military were present during the attacks.

Activists feared that the military would use the crisis as an opportunity to restore (other) repressive aspects of the former Mubarak regime, citing increased repression of journalists and intolerance of criticism of the Army.

While the rule of Egypt’s first democratically elected President was not what some Egyptians had hoped for, the idea of democratic legitimacy has taken a severe beating with Morsi’s ousting. Although the military claimed to act on behalf of ‘the will of the people’ and Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, the Defence Minister who led the coup, was initially hailed as a national hero, the repression and detention of Muslim Brotherhood-members and increased polarization has jeopardized the hope for a successful democratic transition. As of October 2013, demonstrations against the military-backed regime were ongoing.

The international community

The continued unrest upped the pressure on the United States to cut off its military aid to Egypt. The United States however, refused to call the ousting of Morsi by the military a ‘coup’, since doing so would jeopardize the USD 1.3 billion worth of financial support Egypt receives annually. The United States’ interest is to safeguard Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel. In addition the United States has commercial interests (mainly the arms industry). It would furthermore endanger Israel’s security (given the insecurity in the Sinai).

However, in a press statement, the Obama administration in October 2013 announced it would suspend the delivery of large-scale military systems and financial assistance to the government, ‘pending credible progress toward an inclusive, democratically elected civilian government through free and fair elections’. According to the Financial Times, financial assistance worth 260 million USD and a 300 million USD loan guarantee to buy military equipment were suspended. In the meantime, humanitarian aid and assistance to counter-terrorism operations were continued. Saudi Arabia welcomed the military’s move (it did not call it a coup) and offered billions of dollars of support, as did the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.

Morsi's foreign policy

In contrast to his predecessor Hosni Mubarak, whose foreign policy was directed to preserving the status quo (a guarantor of regional stability and a reliable ally for the United States), Morsi declared to restore Egypt’s historical predominance. Instead of prioritising the United States or Europe, Morsi first visited countries like Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, China and Iran, the latter of which Egypt had not had diplomatic relations with since 1979.

Relations with the Gulf countries were on the early agenda of the new President, and he travelled to Saudi Arabia to strengthen ties. The Emir of Qatar visited Egypt and promised Egypt USD 2 billion.

Morsi attended the African Union summit meeting in Addis Ababa, which was the first visit of the Egyptian head of state to Ethiopia in seventeen years. Hosni Mubarak had stopped attending after an attempt was made on his life there in 1995.

At the end of August 2012, Morsi attended the Non-Aligned Movement summit in Tehran. Many hailed Morsi for criticizing Syria’s Bashar al-Assad for his massacre of the Syrian people and for criticizing Iran for not taking a strong stand against al-Assad. Opponents in Egypt disregarded Morsi’s stance as mere words that are unlikely to be put into practice.

However, while Egypt initially took a neutral stance towards the war in Syria, Morsi cut diplomatic ties with Syria in June 2013. He also demanded that the Lebanese Shiite Hezbollah movement withdraw from fighting in Syria and called for the international community to impose a no-fly zone over Syria.

President Morsi promised to uphold Egypt’s commitments under international treaties, including the peace treaty with Israel. Morsi secured a cease-fire between Hamas and Israel in November 2012.

According to the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Morsi’s foreign policy, in contrast to his domestic policy, was no ‘Islamist’ project. Among the various political camps there was a consensus concerning the country’s leadership role and ending the dependency on the West. Morsi visited many non-Muslim and non-Arab states, in order to send a message that his Islamist current was moderate and which the world could do business with.

Although Morsi proved successful in trying to spread his message of moderation, critics argued that his foreign policy strategy was not clear and that Morsi was more busy with domestic political concerns.

At the same time, foreign financial and economic aid to Egypt increased. Saudi Arabia promised financial support amounting to $4 billion; Qatar promised $2 billion and announced to invest $3 billion in industry and tourism projects. In September 2012, Turkey announced a $2 billion aid package.

Drafting a new constitution

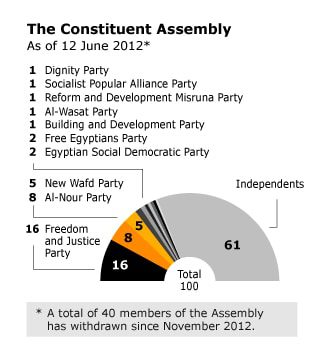

The Constituent Assembly in 2012 The process of drafting a new Constitution began in March 2012. The composition of the body drafting the Constitution, the Constituent Assembly, has been contested from the start. Half of the Assembly consisted of Members of Parliament, which itself was dominated by members of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party and by members of the Salafist Nour Party. Islamists dominated the other half of the Assembly as well. Fearing the consequences for the character of the new Constitution, liberal and leftist members decided to leave the Assembly en masse, as a result of which a third of the Assembly seats became vacant. Dysfunctional as it had become, the Assembly was dissolved by court order on 10 April 2012.

The process of drafting a new Constitution began in March 2012. The composition of the body drafting the Constitution, the Constituent Assembly, has been contested from the start. Half of the Assembly consisted of Members of Parliament, which itself was dominated by members of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party and by members of the Salafist Nour Party. Islamists dominated the other half of the Assembly as well. Fearing the consequences for the character of the new Constitution, liberal and leftist members decided to leave the Assembly en masse, as a result of which a third of the Assembly seats became vacant. Dysfunctional as it had become, the Assembly was dissolved by court order on 10 April 2012.

Under pressure from the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), Islamists led by the Muslim Brotherhood reached an agreement with minority parties, requiring a 50-50 ratio of Islamist to non-Islamist members and a reduction of the number of seats reserved for members of the Islamist-dominated Parliament.

A new Assembly established on 12 June 2012 was made up of members of the wider Egyptian society – politicians, members of Armed Forces, the judiciary, police and trade unions, as well as Christian leaders. However, an atmosphere of distrust towards the Muslim Brotherhood remained, the latter being accused of trying to monopolize the Assembly. On 17 November, representatives of all Egyptian churches, including the Coptic, Catholic and Evangelical denominations walked out in protest of the Islamists’ alleged failure to compromise on key issues.

On 14 June 2012, Egypt’s high court ordered the dissolution of Parliament, because political parties had run for individual seats in the November 2011 elections, a practice that was ruled unconstitutional. Following the ruling, lawyers argued for the dissolution of the Assembly as well.

Amidst the threat of a second dissolution, President Muhammad Morsi on November 22 issued a constitutional declaration granting himself additional powers and protecting his actions from judicial oversight. Morsi decreed that no judicial body may dissolve the Constituent Assembly or the Shura Council (Article 5). The step was seen as a strike against Egypt’s judiciary: most of the judges had been appointed by deposed President Hosni Mubarak.

It was the second time that Morsi used his authority to challenge institutions of the former Mubarak regime. Earlier he ordered a re-trial of all Mubarak officials who were implicated in violence against peaceful protestors.

In his constitutional declaration, Morsi gave the Assembly an additional two months to finish its work. Yet, already on 30 November 2012, the Assembly approved a rushed version of the draft Constitution to avoid dissolution by the Supreme Constitutional Court, whilst under a boycott by the opposition. The following day, Morsi announced a national referendum on the draft Constitution.

Morsi’s declaration sparked mass protests throughout Egypt. Opposition activists took to the streets to protest against what they regarded as dictatorial measures and a coup by Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood. In Cairo protesters stormed Muslim Brotherhood offices and the Presidential Palace, demanding the referendum to be cancelled. Morsi’s supporters, however, regarded the declaration as an important step for the President to take control and protect the country against remnants of the old regime whom they have held responsible for the lack of change after the ousting of Mubarak. The judiciary went on strike in response to Morsi’s decree.

On 8 December 2012, Morsi announced that his declaration had been annulled, removing his immunity from judicial oversight. Yet, as the Constituent Assembly had finished its work, the threat that it might be dissolved, subsided. Morsi had been helped by the accelerated production of the draft and no longer needed his November 22 decree.

Referendum

Although Morsi had annulled his controversial constitutional declaration, he refused to delay the upcoming referendum. The opposition complained that the rushed production of the draft and the short period leading up to the referendum prevented any meaningful debate on its provisions. The text of the Constitution has been criticized for not being particularly accessible to ordinary Egyptians. The vote was met with considerable opposition, with the National Salvation Front, a coalition of liberal, leftist and centrist parties, calling for a ‘no’ vote.

The referendum was held in two rounds on 15 and 22 December 2012, as many judges had withdrawn from supervising the vote in protest.

End results showed that 63.8 percent of voters supported the draft Constitution. Since only 32.9 percent of eligible voters participated in the referendum, the legitimacy of support has been contested. Participation was lower than in earlier polls: 62 percent of eligible voters had taken part in the parliamentary elections in December 2011/January 2012, while voter turnout was 51.8 percent in the presidential elections in May 2012. After the referendum, the opposition claimed that the vote was marred by fraud.

The Constitution

Much is at stake concerning the draft Constitution itself. Morsi and his supporters have emphasized that the new Constitution is necessary in order to seal the transition from decades of military-backed rule, while opponents have stated that it is heavily influenced by Islamists and that it ignores the rights of Egypt’s minorities and women.

Although the text is relatively favourable to the aspirations of the revolution – such as more power for Parliament, limitation of presidential powers, freedom of assembly and organization – it has been criticized for being vague and ambiguous. Rights defined in one article are either limited in another or are insufficiently defined, leaving some provisions open to interpretation. The opposition, led by prominent figures like Muhammad al-Baradei (The Constitution Party), Hamdeen Sabahi (co-leader of the National Salvation Front) and Amr Musa (former Minister of Foreign Affairs, 1991-2001), fear that these ambiguities will open the way to strict Islamic law.

A source of concern for liberal, secular and Christian Egyptians has been the role of Islam in the Constitution. Although Article 2 was left unchanged (‘Principles of the Sharia are the principle source of legislation’), the way the article is to be understood and applied has changed. Interpretation of the ‘principles’ was formerly left to the courts (based on rulings on which there was consensus), but with the new Constitution, this has changed. Article 219 has widened the scope of ‘principles’; it includes all the rulings of Islamic jurisprudence and credible sources accepted in Sunni doctrines (the Koran, the Sunna, Hadith).

Matters can be adjudicated according to these sources, even if they do not exist in the statutory laws. Islamic law being open to interpretation, Article 4 states that the opinion of al-Azhar must be obtained in all matters relating to the Sharia. It has not been defined who shall seek al-Azhar’s opinion or for what matters specifically. In the old 1971 Constitution, there was no article on the role of al-Azhar. Salafis have in fact been pushing for Article 2 to be changed to the Sharia itself being the principle source of legislation.

At first glance, rights and freedoms are protected in the Constitution. Yet, closer reading reveals several restrictions. Article 81 on the rights and freedoms of the individual has been curtailed by the addendum: ‘Such rights and freedoms shall be practiced in a manner not conflicting with the principles included in the State and Society Part of this Constitution’. The same is applicable to Article 48 regarding the freedom of the press. Freedom of expression has been limited through a number of articles throughout the Constitution’s text. While Article 45 grants freedom of thought and opinion without limitations, other provisions do define limitations. (Article 44: ‘Insult or abuse of all religious messengers shall be prohibited’; Article 31: ‘Insulting or showing contempt toward any human being shall be prohibited’.)

Article 43 on freedom of religion limits the right to practice religion and to establish places of worship to Muslims, Christians and Jews. While the 1971 Constitution provided for a general right to practice religion, the new Constitution discriminates against followers of other religions, including Bahais. In addition, although Article 30 ensures equality in citizens’ rights and obligations, Article 10 has been criticized as it implies that the state is able to interfere with a woman’s personal choices (‘The State shall balance between a woman’s obligations toward the family and public work’).

In the draft Constitution, separation of powers is ensured. Parliament has been given significant authority in the government formation. Any government plan must be approved by Parliament (Article 139) and the Prime Minister and his ministers can be questioned and dismissed (Article 126). Even individual members of Parliament have the right to question ministers (Articles 123-125). In addition, the President’s powers have been limited. The number of terms has been limited to two (Article 133). However, the President still appoints one tenth of the members of the Upper Chamber of Parliament (Article 128).

In addition he appoints the heads of nearly all independent agencies (Article 202), including the audit institution and the central bank, threatening their independence and ability to monitor the executive. Finally, the Constitution has placed central government over local authorities, maintaining Egypt’s highly centralized form of government. Article 190 states that any decision by elected local councils may be overturned by the central government. How governors will be chosen and what their powers are, is not defined in the Constitution (Article 187).

Article 197 states that a 15-member National Defence Council will be established, with members from the government and military. The Council will determine the budget allocated to the military, and will provide it as a single figure in the national budget, preventing adequate oversight by the Parliament. It will also have a say in draft laws concerning the Army.

While ending military trials of civilians has been a key revolutionary demand from the start, military trials have been allowed in case of crimes which ‘harm the armed forces’ (Article 198). Earlier drafts had explicitly banned military trials for civilians. The new Constitution does provide for strong protection against arbitrary detention (Article 35) and torture and inhumane treatment (Article 36); freedom of assembly and association (Articles 50,51), according to Human Rights Watch.