The north-west of Syria, specifically the Idlib region, saw a large-scale military escalation in May 2019, with numerous air strikes by the Syrian government and Russia. In addition, the Syrian army and auxiliary forces launched ground assaults, taking over several localities, notably in north Hama. What is the reason for this escalation? Is this the final campaign to retake the last major insurgent stronghold in Syria?

The short answer is no. A correspondent for the Russian outlet ANNA News who has been on the frontlines and a member of a pro-government formation who is originally from Idlib province both made clear that the aim of the present operations is not to retake the entire north-west region. Rather, the aim is to retake specific areas. As the second source put it: “They are pressure operations only to implement the clauses of the agreement of demilitarized zones.”

The Russian correspondent offered more clarification: “The insurgents have not complied with the Sochi agreement and have fired mortars on safe areas and Hmeimim airbase. They have also launched various attacks on the points of the Syrian army from their areas in north Hama, the al-Ghab plain and north-east Latakia countryside. This operation aims to put pressure on the insurgents and implement the agreement by force, while opening the Aleppo-Latakia and Aleppo-Damascus highway.”

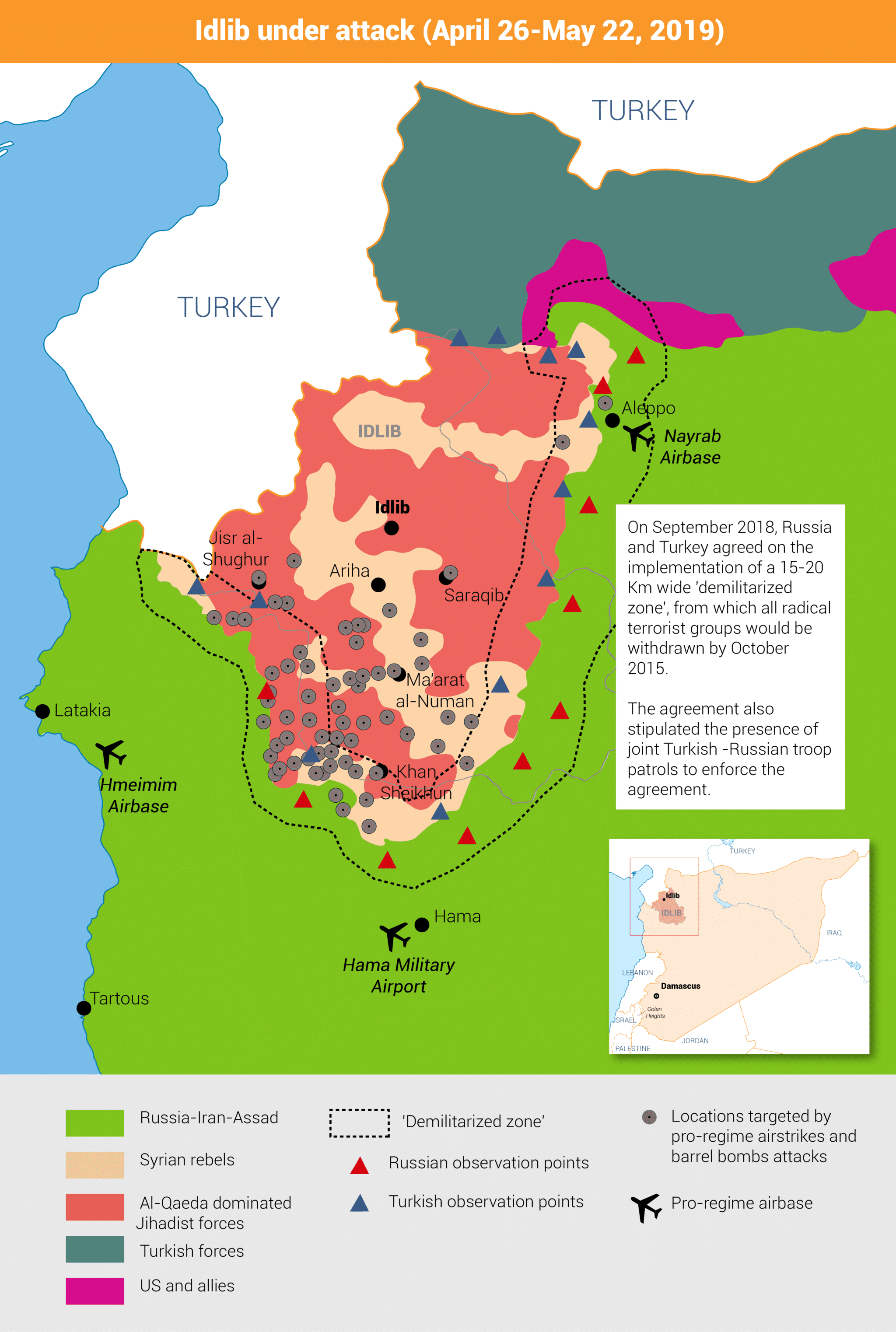

In other words, the current escalation stems from the frustration of the Russian and Syrian governments with Turkey for its perceived failure to uphold its end of the bargain in the Sochi agreement. The agreement was signed in September 2018 between Turkey and Russia and called for the preservation of the original ‘de-escalation’ area that had been agreed for Idlib. Russia committed to ensuring that there would be no military operations against Idlib, but the agreement also stipulated the establishment of a 15-20km wide ‘demilitarized zone’ from which ‘all radical terrorist groups’ would be removed by 15 October 2018. Although Russia and Turkey were to conduct joint patrols to enforce the demilitarized zone, the M4 (Aleppo-Latakia) and M5 (Aleppo-Hama) highways would also be opened.

The agreement reflects Russia’s desire to advance the interests of the Syrian government (especially with regards to economic recovery in opening the highways) while also taking into account Turkish concerns about a potential surge of refugees towards Turkey’s borders in the event of a large-scale offensive on Idlib.

Though it is difficult to determine how exactly things would have been worked out in the long run under the scenario of fully implementing the agreement, it is probable that Russia envisioned an eventual ‘soft landing’ and return of the Idlib area to Syrian government control.

Earlier this year, Turkey began deploying patrols as part of the supposed enforcement of the Sochi agreement. However, most of the other terms of the agreement were not implemented. Although the agreement did not specify the ‘radical terrorist groups’ to be removed from the demilitarized zone, it is almost certain that from Russia’s perspective at least the groups included Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which poses a particular problem as it is the dominant actor in north-west Syria. HTS originated in Syria’s al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra but broke ties with al-Qaeda.

HTS’ own stance towards the Sochi agreement has been highly controversial in jihadist circles. In the view of more hardline jihadists, HTS has supposedly been complying with the agreement by permitting the Turkish patrols and freezing the military frontlines in the north-west.

These jihadists view the supposed HTS stance as part of a broader pattern of the group’s unacceptable compromising of principles to reach an agreement with Turkey, which is reluctant to confront HTS militarily. Even so, prior to the latest escalation, there were localized clashes between pro-government forces and insurgents and attacks on Hmeimim airbase in Latakia. A proper de-militarized zone cleared of HTS and other jihadists was not actually created.

For its part, Turkey is unlikely to engage in direct military intervention on behalf of the insurgency, but it can ‘counter-escalate’ indirectly in an attempt to convince Russia and the Syrian government that the cost of their current limited offensive will be too high. For example, some members of the ‘National Army’ of rebel forces based in the Turkish-occupied north Aleppo countryside have been participating in operations on the frontlines. Since the National Army forces cannot mobilize and engage in operations without Turkish consent, Turkey must have permitted their participation as part of a counter-escalation.

There have also been reports that Turkey has provided additional weaponry for rebel forces, including TOW missiles that the United States (US) has to approve for release from storage. That the US would allow the insurgents to be bolstered in this way reflects its own opposition to a military campaign by the Syrian government and Russia, even though the US was excluded from the original de-escalation framework and Sochi agreement.

In turn, this counter-escalation may lead to greater Iranian support for its Syrian ally. Iranian-backed units of Syrian fighters can certainly be found in Latakia, Hama and Aleppo provinces in areas that are near the frontlines with the insurgent-held zones, but they have not been playing any leading roles in the current offensive. That could change if the situation continues to escalate.

In any case, while the fighting will prove difficult for both sides, the balance of power is ultimately tipped against the insurgency, short of a direct military intervention by an international actor on its behalf.