Turkish products sold in Iraqi Kurdistan can be recognized by a barcode starting with the numbers 868 or 869. These make it easier for Kurds to boycott Turkish products in protest against Turkey’s invasion of north-eastern Syria on 9 October 2019. Or does it? It may also confront them with their high level of dependence on Turkey, making it close to impossible to implement such a boycott. And what can the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which depends politically on Ankara’s support, do to defend the Kurds in Syria?

The implications of the invasion by the Turkish army, in cooperation with assorted jihadist groups, are potentially huge for the KRG. Together with the Iraqi government, it has stepped up its border security to prevent a possible influx of members of the Islamic State (IS). The resurgence of the group, which was pushed from its last pocket of territory earlier this year by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), was also the topic of the first statement that the KRG made after American President Donald Trump announced that the United States was withdrawing its remaining troops from Syria. By now, hundreds, if not more than a thousand, IS members have escaped from prisons and camps that were guarded by the SDF until the invasion. Women (and children) escaped from Ain Issa refugee and internment camp, which was ransacked by Turkey-backed groups, while men ran away from prisons.

Although the KRG is doing everything it can to keep IS out of Iraqi Kurdistan proper, camps are being made ready for refugees. The KRG’s Joint Crisis Coordination Centre said that with the recent arrival of almost 800 people, the total number of refugees who have entered the region in the past two weeks now stands at 2,000. With more than 150,000 people displaced, this means that only a small portion has crossed the border and the rest is presumably seeking safety elsewhere in Syria, away from the border area where the fighting is concentrated, mostly around the towns of Serekaniye and Tal Abyad, and, to a lesser extent, further east around Qamishli.

With the expected further takeover of Syria’s Kurdish regions and border areas by the Syrian army following a deal struck with the SDF, it seems likely that more people will cross into Iraqi Kurdistan. Most of them reportedly cross the border illegally, as it is becoming harder to reach the official border crossing. The Bardarash camp, which was closed a couple of years ago after housing Iraqis internally displaced from Mosul during the war against IS, was quickly reopened to accommodate the newcomers.

Diplomacy

In an effort to influence developments in north-eastern Syria, the KRG is concentrating on diplomacy. On 7 October, the day after Trump’s announced the troop withdrawal and two days before Turkey attacked, Prime Minister Masrour Barzani met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. During the meeting, Syria was also discussed, with Barzani requesting that Lavrov ‘help promote a long-lasting political solution that protects the rights and dignity of all the Syrian peoples, including the Kurdish people’.

A week in to the incursion, the Kurdistan parliament adopted a list of ‘recommendations’ expressing concern over and solidarity with those affected by the violence. The 12 recommendations included a call to stop the war and increase diplomatic efforts to that end and a pledge to welcome and help refugees, for which (financial) assistance was requested from the Iraqi central government.

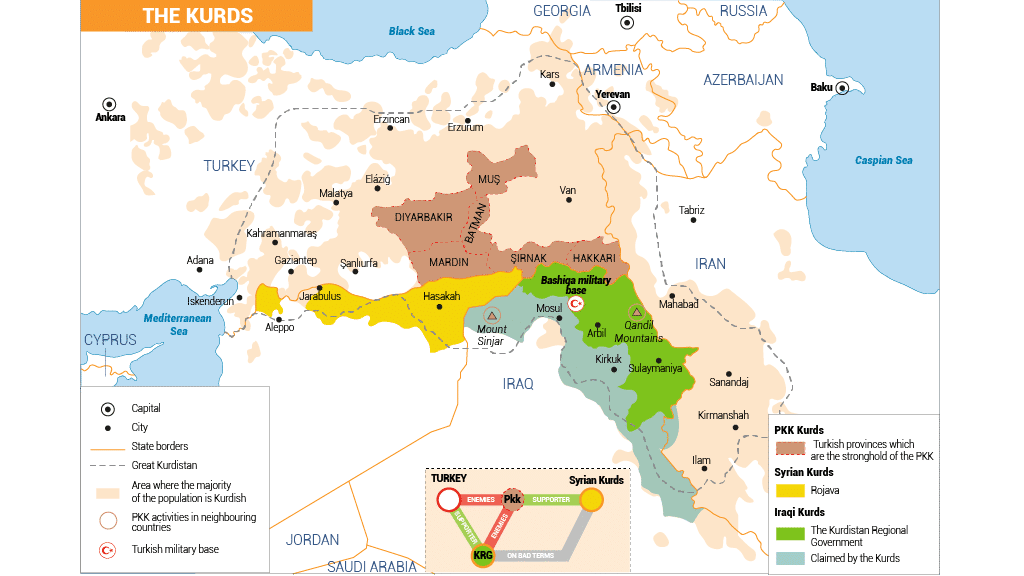

Particularly interesting was the reference to different political factions that have been active in Rojava (Western Kurdistan), as the Kurds call the Kurdish-majority areas in Syria. The parliament called on these factions to ‘turn their backs on narrow ideological and political rivalries and enter a new era of cooperation, public work and civic struggle in the greater interests of the Kurdish people in Rojava’.

Meant here were the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the main political faction in Rojava that has de facto governed the region for the last seven years, and the Kurdistan National Congress (KNC) opposition bloc. Neither bloc has been able to cooperate for a variety of reasons, including the KNC’s marginalization. It should be mentioned that the KNC is ideologically close to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the most powerful party in Iraqi Kurdistan. In other words, the KRG seems to be trying to resolve these rivalries in the broader interests of Kurdish patriotism and solidarity.

Deployment

The KRG’s options to contribute on the ground inside Syria are, however, extremely limited. During what has become a legendary battle against IS for control of Kobani in late 2014, the KDP peshmerga were deployed to the northern Syrian town to assist the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the dominant Kurdish force inside the SDF, laying the groundwork for the cooperation between the Kurds in Syria and the US. A number of members of parliament suggested that the peshmerga should come to the rescue of their ethnic kin in Syria again, but the suggestion is unrealistic for several reasons.

Besides the fact that the peshmerga have no heavy weaponry or exceptional battle skills that the SDF does not already possess, realizing the idea would be a violation of international law.

There are also compelling political reasons against deploying the peshmerga in Syria: the KRG could never take up arms against Turkey. The Turkish army has had a presence inside Iraqi Kurdistan since the early days of its de facto existence in the 1990s and has extended that presence in recent years. After all, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Turkey’s bitterest enemy, has its base camps in the mountains in north and north-eastern Iraq, mostly on territory that is controlled by the KDP. The KDP has no power to prevent this, even if it wanted to.

Turkey’s bombings of and ground operations against the PKK have caused civilian casualties numerous times, the KDP’s response to which is usually to call the PKK to account and not its powerful northern neighbour. Just imagining that the peshmerga would take up arms against Turkey outside their own autonomous region is absurd.

This brings the civilian boycott of Turkish products full circle. If the Kurds really want to stand up to the forces that are trying to bring them to their knees, whether it is the Syrian regime, the Turkish state or any other entity, they will have to unite. But as long as their commercial and ideological aspirations for the future of a Kurdish homeland are not aligned, they do not stand a chance.