As protests continue in Sudan in January 2019, President Omar al-Bashir and his Islamist supporters are facing their toughest test since the army general seized power in a military coup in 1989.

The government in the capital Khartoum has survived numerous protests, the largest and deadliest of which were staged in September 2013 when security forces killed 170 protesters, according to Amnesty International. However, the demonstrations that broke out across the country on 19 December 2018 were different from previous ones in many ways. First and foremost, these protests were in immediate and direct response to an unprecedented economic deterioration caused by the shortage of bread and fuel, forcing people to wait for hours at bakeries and petrol stations.

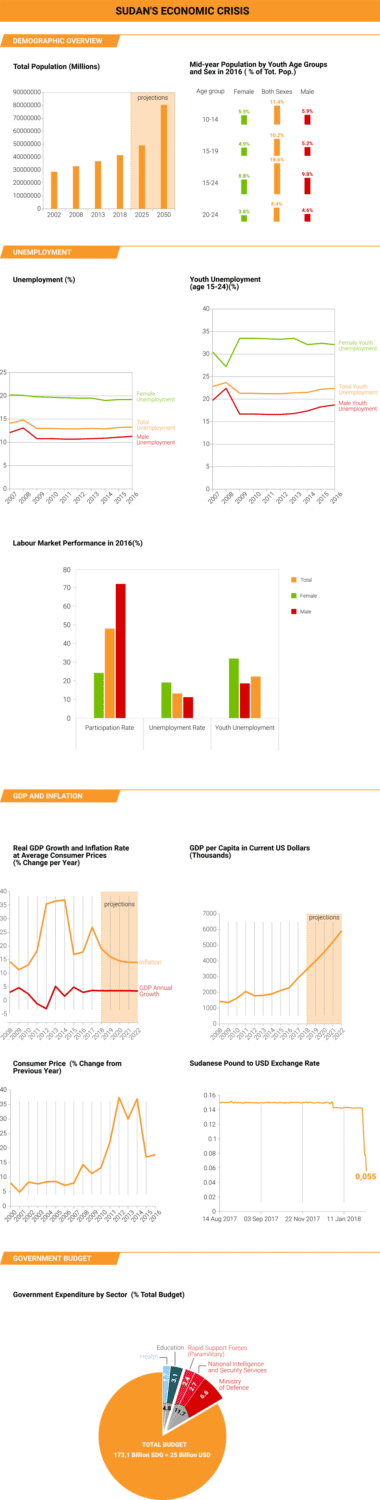

The situation worsened after the government limited bank and ATM withdrawals of amounts exceeding 500 Sudanese pounds (less than $10) per day. The government adopted the policy to curb demand for foreign currency following the devaluation of the pound by 53 per cent, from 29 pounds to 47.5 pounds to the dollar on 7 October. At the same time, the value of the pound on the parallel market (an euphemism for the black market) exceeded 60 pounds to the dollar. The low exchange rate resulted in soaring prices and a cash flow shortage, sparking unprecedented popular anger and a loss of confidence in the banking system.

Waning Popular Support

The demonstrations began in the northern city of Atbara, a historical centre of the Sudanese workers’ movement, in which the headquarters of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) were burned and four demonstrators killed. These were followed by protests in the eastern city of al-Gadarif, the hub of cereal and plant-source oil production. The demonstrations spread to the cities and capitals of governorates where opposition groups and parties are not usually active, eventually reaching Khartoum on 25 December 2018. Further protests were staged on 31 December, 3 January and 6 January 2019, when violence broke out and a number of people were killed and scores of others wounded or arrested.

It is noteworthy that major protests were held in the cities of Atbara, Ad Damar and Karima in the far north, a region that has largely been spared unrest in the past because al-Bashir, First Vice President Bakri Saleh and most of Sudan’s presidents since the country gained independence in 1956 have descended from this region. This development indicates that the regime’s legitimacy and popularity have eroded to such an extent that it may be difficult to recover.

For the government, the most worrying aspect of the demonstrations was the speed at which the initial dissatisfaction with the harsh living conditions turned to demands for al-Bashir to step down. Active political and protest leadership emerged, consisting of opposition parties and the Sudanese Professionals Association, an underground organization that includes dissident doctors, lawyers, engineers, university professors and bankers. The authorities were angered by the gatherings of professionals, which in the 1960s and 1980s spearheaded attempts to overthrow previous military regimes.

The most painful blow came from within the ruling coalition itself, which was surprised by the departure of 22 political parties loyal to the government and representing it on various institutional levels, and their support for the demand that al-Bashir step down. This political trend is led by two veteran politicians, Mubarak al-Mahdi, cousin of al-Sadiq al-Mahdi, leader of the Ummah Party, the largest opposition party, and Ghazi Salahuddin, a dissident of the NCP and its former political secretary.

Both served as ministers in al-Bashir’s governments, as did Shafie Ahmed, former secretary general of the NCP, who sent a letter to members of his party calling for the removal of al-Bashir and the formation of a transitional government headed by the vice president to ensure a peaceful hand-over of power.

The regime’s loss of support has severely impacted the National Dialogue Document approved in 2015 and stripped the government of its last source of political legitimacy. As a result, the NCP is left with a handful of allies who do not have influence outside government institutions.

Bloody Confrontation

In the face of the new wave of protests, the government took violent action in the cities where the demonstrations began. For the first time, hundreds of SUVs mounted with anti-aircraft dushka guns were seen in the streets of Khartoum. Shots were fired in the air in many locations, according to videos posted on social media, in a flagrant show of force aimed at intimidating the protesters. Meanwhile, the police used tear gas canisters and batons, and leaders of the demonstrations accused security and intelligence personnel dressed in civilian clothes of shooting at them.

The information minister said on 27 December 2018 that 19 people had been killed, and that the demonstrators deliberately burned a number of the ruling party’s houses and destroyed public facilities. It later emerged that two of the dead were soldiers who were demonstrating alongside civilians in Atbara.

Amnesty International announced two days earlier that 27 people were killed and hundreds of others wounded and arrested, accusing the authorities of using excessive force and calling for independent investigations into the murder of peaceful protesters. The United Nations Secretary-General issued a similar statement, calling for investigations into the deaths and for the protesters to be allowed to express their grievances peacefully.

Social Media War

Since the first day of the demonstrations, telecommunications companies, at the request of the government, have blocked all social media websites and messaging applications, notably Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp, which were used to mobilize demonstrators.

However, the majority of urban youth were able to bypass the block by using virtual private networks (VPNs) to access the internet. Moreover, VPNs have effectively ended the government’s monopoly of news and made video and audio resources and foreign media freely available.

The government also shut down schools and universities that played an important role in the demonstrations, saying that the measure aimed to protect students from violence. Al-Bashir held a series of meetings with his supporters in the city of Madani in central Sudan and Khartoum, in which he tried to prove his government’s cohesion and promised to resolve the economic crisis and make comprehensive economic reforms as soon as possible – although he has had three decades in power to make these reforms. He added that Sudan was besieged internationally because of its adherence to Islamic Sharia, which the country will never abandon.

Conciliatory Tone

The government initially adopted a conciliatory tone toward the demonstrators. Prime Minister Moataz Moussa said the government recognized the difficult living conditions and understood the discontent of the demonstrators but did not accept destruction of public property. However, the tone soon changed when the protests expanded, and the government accused the Darfur Liberation Movement led by Abdel Wahid Nour of organizing demonstrations and committing subversive acts with support from Mossad, Israel’s secret service.

General Salah Gosh, head of the National Intelligence and Security Service, announced that two groups of Darfur university students had been arrested. They were shown on state-run television confessing to inciting and participating in the demonstrations, acts that are not punishable by law. These groups were known by their fellow students, and they have not left Sudan to receive training from Mossad, contrary to Gosh’s claims.

As the demonstrations entered their third week, the government turned to accusing the small Sudanese Communist Party, a frequent scapegoat, of organizing the demonstrations in an attempt to intimidate the Islamists, some of whom began to change their rhetoric, according to social media websites, and embrace the opinion that there is a hidden conflict between some Islamists and al-Bashir. The accusations levelled at the Darfur Liberation Movement, Mossad and the communists have become a source of widespread mockery.

Regional Isolation

On the Arab regional level, Qatar announced support for Sudan’s regime, following a telephone conversation between Qatari ruler Amir Tamim al-Thani and al-Bashir. Moreover, Egypt sent its foreign minister and intelligence chief to Khartoum on 27 December 2018 to discuss bilateral relations, according to the official daily al-Ahram, which did not make any reference to the unrest in Sudan.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, alongside which the Sudanese army is fighting in Yemen, have not shown any official interest in what is going on in Sudan. However, their satellite channels, such as al-Arabiyah, al-Arabiyah al-Hadath and Arabic Sky News, which are widely watched in Sudan, extensively covered the demonstrations, showing a clear interest in and sympathy toward the demonstrators, as evidenced by the guest speakers invited to comment and the airtime dedicated to them.

It seems inevitable, if his long tenure is any indication, that al-Bashir will survive this crisis, albeit considerably weakened and with far fewer influential allies. However, the next wave of protests may not be far off if the government does not make any viable attempts to ease the economic conditions that prompted the people to take to the streets in the first place.